Words by Colin Whelan | Published 08.08.2025“But in terms of actually being a co-commentator, you know, you could be at a World Cup Final, European Cup Finals, FA Cup Finals, you name it. Everything that I’ve done, none of them compare with the least important game of football I played. None of them. Not one.”

- Pat Nevin

It is well known in football - indeed Pat Nevin’s autobiography somewhat gives the game away - that Pat Nevin became a full-time footballer by accident. ‘The Accidental Footballer’ covers the story in greater detail, and particularly how Pat had accidentally got himself picked for the Scotland under-18s squad that headed off to Finland to contest the 1982 under-18s European Championships. How he was accidentally part of the team that beat Czechoslovakia 3-1 in the final, accidentally scoring one of the goals. And as an accidental bonus, how Pat Nevin was named ‘Player of the Tournament'.

Pat Nevin was just a very good footballer, from a very early age. His dad had taught all the boys in the family how to play football, but it was only Pat who stuck at it and wanted to learn more. His dad would spend hours and hours with his son, teaching him all the skills and techniques he had himself observed at Celtic’s training ground and from the football coaching books he had read. Unorthodox, maybe, but this was the way that Pat learned to dribble without looking at the ball, the endless repetitive drills and running that gave him the abundant stamina to run for a full 90 minutes on a football field.

But this was never meant to be, of course. Nevin had only joined second division Clyde on a part-time basis, to supplement his income as a student studying for a degree at Glasgow College of Technology. He had actually been taken on and then rejected by Celtic, but at the age of 17 his attentions were more drawn towards the arts, music and study. If you had added wine and women to that list, you would have the complete list of the typical reasons – the ‘escape card’ in Nevin’s case - why so many young men don’t fulfil their footballing talent, when offered an opportunity at a club.

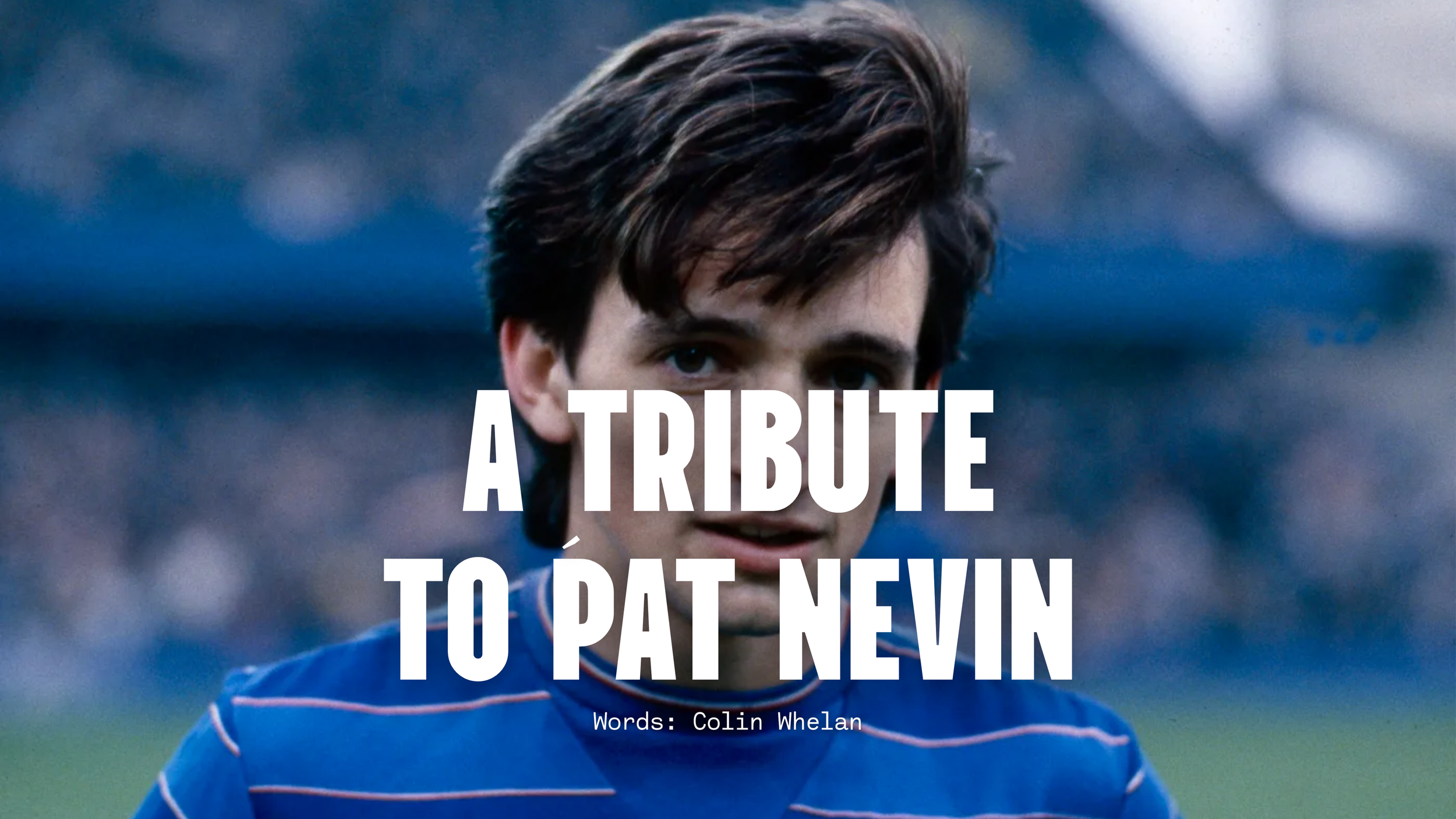

A young Pat Nevin at the start of his career with Clyde FC.

Photo Credit: SNSHowever, the success he had achieved at a very early stage of his career encouraged Pat to convince himself that he could take a two-year sabbatical from study, and see where this football lark would take him. The lark suddenly turned serious, when Chelsea took him away from Clyde for a fee of £95,000 and then paid him £180 per week – Pat Nevin was now a proper football player.

He arrived in London at the same time as fellow Glaswegian Charlie Nicholas, in the summer of 1983. Ironically, both were attracted to London’s night life; but whereas Charlie loved a late night, surrounded by a ‘bevy of beauties’ and photographers in the latest ‘Crash, Bang, Wallop’ nightclub London could offer, Pat would hide away from view, wearing a trench coat at a Jesus and Mary Chain gig, sipping on a half of lager. Here was a serious indie music fan, who revelled in – but never abused - the opportunities London brought to his door. London and Pat Nevin were made for each other, in the best way possible.

He settled into London life easily, and the Chelsea fans soon singled him out for special praise. Here was the throwback and natural successor to Chelsea’s last great Scottish winger, Charlie Cooke. But Pat Nevin would run all day, too, never considered a luxury as a winger, able to track back and challenge full-backs venturing into the opposition half.

But there was always something different about Pat Nevin. An indie music fan, with an experimental quiff, he wasn’t your typical footballer with mid-80s blond highlights. To any indie fan, he was a godsend. We weren’t blessed with Morrissey in a central midfield role at Man United, but we still loved Pat Nevin at Chelsea. And football was ready – just about - to welcome an ‘outsider’, to accept into the fold a winger who worked tirelessly for his team, despite not looking the norm.

And it was during his first season at Chelsea, that he truly lifted his head above the parapet, announcing to the world who he truly was; what made him tick; and what would draw his ire. He’d scored the winner against Crystal Palace in a Division 2 game, in April 1984, and as reporters waited outside the dressing room, to speak to the match-winner, a fuming Nevin stormed out “I’m not talking about the game, I’m disgusted with these people who pretend to be Chelsea fans. There’s no place for that”.

“These people” Pat had referred to, were the Chelsea fans, who had been booing and throwing bananas at Chelsea’s own debutante Paul Canonville, the first black person to play for Chelsea.

What Nevin did that day lit the touchpaper. Very few footballers had ever called out fans in general; none had ever called out their own fans. Managers rarely did, either. Pundits and commentators did, but from a position of relative detachment. But thanks to the brave words of Pat Nevin that day, a far greater awareness was formed.

Pat Nevin signed for Chelsea from Clyde at the age of 19, and became a star.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesBit-by-bit, football recognised it had a problem with racism. Wider society had already begun to address its own problem, and had legislated against racism a decade earlier. However, it couldn’t legislate against prevailing attitudes - that would take many years to overcome. Nor did it legislate against the indescribably cruel racist taunting and name-calling

Gradually, we fans acknowledged that football had a specific problem, a problem it was reluctant itself to admit to, blaming, instead, ‘wider society’ for the scourge of racism. But it was football, no other sport, that appeared to be the meeting point for the racists. No one tackled what was going on in football, it just had its own laws in the 70s and 80s – it was left to football to sort out its own mess. It and its fans would be left to fight and fester inside its own bubble – it didn’t need to be the concern of wider society.

But, steadily, after Pat Nevin’s outburst, we saw local alliances and wider movements formed to challenge racism, specifically in football. The ‘Kick it Out’ campaign is the most long-running and recognisable drive to address the blight of racism within all UK sports, having started as a football-only movement in 1993.

Pat, himself, was part of these movements, and he developed other extra-curricular responsibilities as a footballer, when he became the Chair of the Professional Footballers’ Association in 1993. He even had a stint as a Chief Executive – and a player – at Motherwell in 1998.

We shouldn’t forget, either, Pat Nevin’s 28 caps for Scotland, and his place at the 1992 Euros; nor his £925,000 transfer to Everton in 1988, and the part he played in Everton’s run to the 1989 FA Cup Final. And after that, he saw out his career via Tranmere Rovers and Kilmarnock. He even managed to earn a place in Tranmere’s ‘Hall of Fame’ in 2010, despite only playing three seasons at Prenton Park.

After spells at Everton, Tranmere and Kilmarnock, Pat Nevin signed for Motherwell before retiring in 2000.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesBut there was always something intriguing and genuine about Pat Nevin. The ‘Weirdo’ nickname stuck at Chelsea, but it was never delivered with anything other than affection. His team-mates and fans knew his great worth to the team – you don’t earn two ‘Player of the Season’ awards for being unpopular. He really was that sort of player that fans love – exciting and creative on the pitch, but hard-working, too. But Pat was smart as well – it was an honour to have an intellectual in your team, especially someone as cool as him.

Pat Nevin was actually way beyond an accidental footballer. His part in the football story of the 80s rises way above that, as his agitating zeal elevated him as the worthy successor to Jimmy Hill, football’s great agitator of the 60s.

Football has Pat to thank – not solely – for highlighting that football had a problem with racism. Racism in football was so bad in the 80s, that some fans thought it more than OK to abuse their own black players. Pat Nevin’s bravery, and his insistence that he would be heard, forged the path that others would follow. Players themselves now call out racism if they hear it on the pitch; others have walked off the pitch in protest. Racism still exists in English football, but it doesn’t present the menace it once did, scaring and scarring potential fans of colour.

Still a broadcaster and still a writer of football, Pat Nevin is acknowledged as one of the very best people in the game. Pat is loved for his authenticity. An indie music fan, still delivering sets to discerning audiences; someone whose intellect and voice stands above his contemporaries.

The footballer by accident, who could never quite let go, it is our great privilege that he is still part of our wonderful game.

Pat Nevin - the indie kid who couldn’t let football go and always sang to his own tune.

Photo Credit: FourFourTwo