Words by Colin Whelan | Published 21.10.2025“I played games when I shouldn't because they asked me. I had injections in various parts of my body, directly into my knee joint, into my stomach, to get me on a football pitch because they needed me”.

– Andy Gray

There’s a passage of play in the game between Everton and Watford, played out at Goodison Park in February 1985, that culminates in Gary Stevens scoring one of the two goals he scored that afternoon. Trevor Steven and Kevin Sheedy added the other two, as Everton extended a winning run that would culminate with a League Championship and Cup-Winners’ Cup triumph that season. Leading the celebrations for all four goals – not with a ruffling of the hair and a handshake for the goal-scorer, but instigating a full-scale team pile-on – was Everton’s centre forward; the same centre forward, in fact, who had not scored a goal for Everton since 15 September 1984.

This is what Andy Gray brought to Everton. A mere snip at £250,000, Howard Kendall knew that a close-to version of the very best Andy Gray would deliver goals, provide great link-up play, instil a passion to play and a desire to win, that would inspire a team to achieve far greater than the sum of its parts. A young team, led by an ambitious manager, gradually assimilating the nous and experience of a Gray and a Reid. The challenge, the gamble, for Kendall would be to keep Gray and Reid fit enough, so that Everton would see the best possible versions of these stalwarts, and that the team could win trophies.

Because until Andy Gray joined Everton in November 1983, a career that had promised so much had largely disappointed. A player so good, that in 1977 he had won the ‘PFA Player of the Year’ and ‘Young Player of the Year’ awards. “So good”, that only Cristiano Ronaldo and Gareth Bale have since won that particular double.

But after that season – where he was also the joint ‘Golden Boot’ winner, with 25 goals – there appeared to be a steady decline. A willingness to throw his body at anything that moved, to throw a leg or a forehead at a ball within scoring distance, had led to an increasing amount of time spent on the treatment table. Here was a fearlessness presenting itself as reckless.

From 1978 onwards, Gray would miss between a quarter and a third of his teams’ matches – his bravery had become a liability.

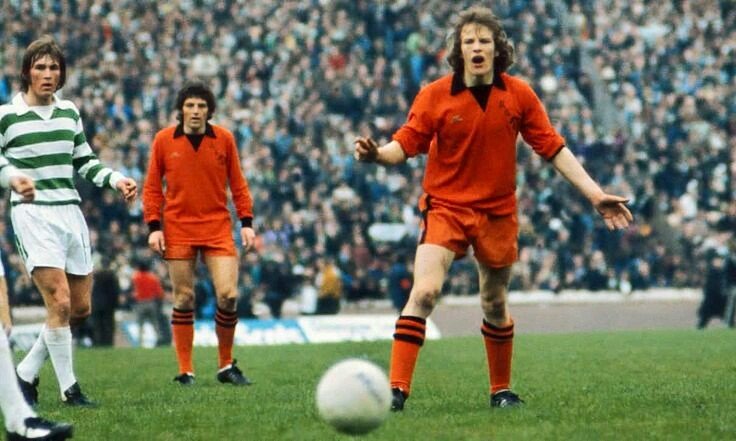

Andy Gray in action in the Scottish Cup Final, 1974.

Photo Credit: Picture This ScotlandThat didn’t, however, stop Wolves from breaking the British transfer record to secure Gray’s services in September 1979. The till paused its kerrchinging at £1.47m, in a year when the British record transfer fee had been broken four times. That Gray had already lost respect for boss Ron Saunders at Villa, meant that he didn’t need much persuading to leave.

And Gray made an impact in his first season, as he scored the winner in the League Cup Final against Nottingham Forest. But soon the ‘injury prone’ and ‘liability’ tags were being thrown around, as he could only score 24 goals in 86 league appearances, over the next three seasons. Wolves also suffered a relegation and immediate promotion during his time there.

To add the insult to injury, he only had to glance down the M6, to watch the team he had left, Aston Villa, racing away on their own run of glory, scooping up a League Championship and European Cup in 1981 and 1982, respectively.

But it was that move to Everton, where Andy Gray found his true home. Sensing, maybe, that this was his last shot with a big club, Gray launched himself into his new role, an act which would prove to be unforgettable, a legacy cemented forever; his name forcing its way into any ‘List of Goodison Legends’. Gray also recalls fondly the similarities between the city of Liverpool and the city of his birth, Glasgow. The maritime links, the iconic river, the humour – these all helped Andy Gray feel very much at home and very content.

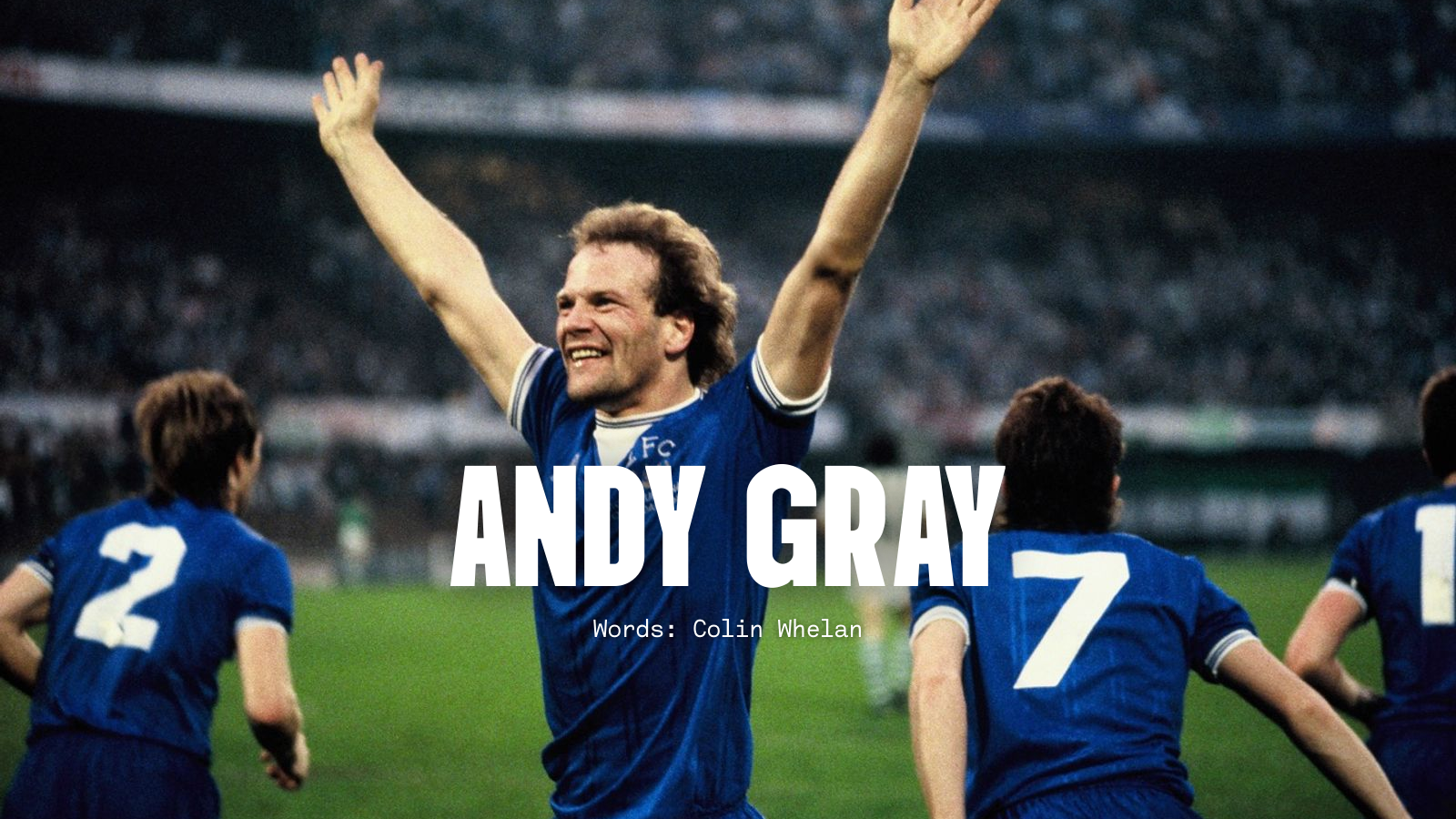

Andy Gray applauds the Everton fans after a 2-0 victory against QPR on May 6, 1985.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesIt was the determination to prove himself that Howard Kendall had bought into when buying Andy Gray. He had also bought midfield dynamo Peter Reid from Bolton the previous season for £60,000, another player whose early promise had been wasting away on a treatment table. And it was the influence and presence of these two, in particular, that the younger players at the club latched onto. Battle-hardened warriors, who maybe carried too many badges of honourable conflict over the years, but who, in the right setting, would give their all to fight a winning cause. It was their sheer will, their encouragement, their example – expertly marshalled by Kendall - that carried that Everton team to its greatest glories.

And, specifically, there’s a 19-month period in Andy Gray’s footballing career, where his early promise was fulfilled, and his ability and determination reaped its just rewards. During his 68 appearances at Everton, he won a League, an FA Cup, a Cup-Winners’ Cup and a Charity Shield, scoring 25 goals in the process.

He scored the goals when it mattered, too. An unthinkable diving header half-volley in a FA Cup quarter-final against Notts County; a header in the Cup Final against Watford in 1984; a ‘right place, right time’ volley against Rapid Vienna in the Cup Winners’ Cup Final in 1985. And not forgetting the two memorable diving headers against Sunderland in the league campaign at Goodison in March 1985.

There was also the night that Andy Gray rampaged his team into their first-ever European final, against European royalty Bayern Munich in the semi-final of the 1985 Cup Winners’ Cup. A noise had never been heard quite like it that April evening at Goodison, as a frantic Everton - 1-0 down on the night – sought parity first, victory second, to book their place in the final in Rotterdam. Two Gray assists and a tap-in later, Everton were in their first European final - and the tv cameras were shaking. Andy Gray had both terrorised and ran the Bayern defence ragged that night. “You can take one game to the grave with you” - his own words. Andy Gray and the 49,476 official Everton fans that night would live that quote for the rest of their lives.

Andy Gray scores Everton’s first goal against Rapid Vienna in the European Cup Winners Cup Final, 1985.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesThere can be few players, ever, who hold such a positive ‘games played: trophies won’ ratio, at any club. It wasn’t just the goals, it was the galvanising influence in the dressing room, the leadership and presence. As well as scoring the goals when it mattered, it was that will to win that rubbed off on all his team-mates.

You suspect, too, that Andy Gray couldn’t believe his luck that he had joined a team just on the cusp of greatness. His own career had stalled until this point, and he had been unsure of his next move. Howard Kendall had offered a chance of resurrection – Andy Gray was determined to make the most of everything good that would now come his way.

But his luck ran out. At the start of the next season, manager Howard Kendall made a personal call to Andy Gray’s house, to break the news that Everton had spent £800,000 to bring Leicester striker Gary Lineker to the club. Adrian Heath was also back to full fitness, and Kendall would struggle to give Gray playing time in the new set-up. Gray was devastated, as were the fans who had grown to idolise him over the past two seasons. They signed a petition to persuade Everton to change their mind, but to no avail – Gray was on his way back to the Villa.

Maybe Kendall was right all along; maybe he had eked out almost every last sinew of ability, fitness and luck from Andy Gray. He scored 5 goals in 54 appearances back at Villa, as they were relegated. A season at West Brom was followed by one last SPL triumph back in Scotland with Rangers, scoring five goals in 14 appearances.

Andy Gray (right) playing for Cheltenham Town, his last club, in the Midlands Flooflit Cup final, 1989.

Photo Credit: Hinckley TimesA career based on aggression, fearlessness, sometimes recklessness, would always suffer its downsides and shortfalls. He’d played in a Scottish Cup Final at the age of 18 for Dundee United, but he made his career and name in England. His international career never really took off, only winning 20 caps and scoring seven goals. It’s true that Scotland had an abundance of options between 1978-86, covering all positions, but Gray never did play at any of the three World Cups they had qualified for. That seems less an oversight, more criminal negligence.

But Andy Gray scored in three different cup finals for two of the English teams he played for. He played in an Everton team in the 1984-85 season, that rose from almost nowhere to check the domination of Merseyside neighbours Liverpool and to lift the city to its greatest heights, during its worst social and economic decline.

He was that teams energising and invigorating force, the general up front, imploring others to be like him. Andy Gray played 68 games for a team that he loved, and a team who loved him, and he made the very most of any talent bestowed upon him.

His fearless approach to football ensured that his career would always be one of great lows, followed by the greatest of highs. Everton fans saw him reaching those great heights, all in the name of their greatest-ever team.

They were truly blessed. As all us neutrals were, too.