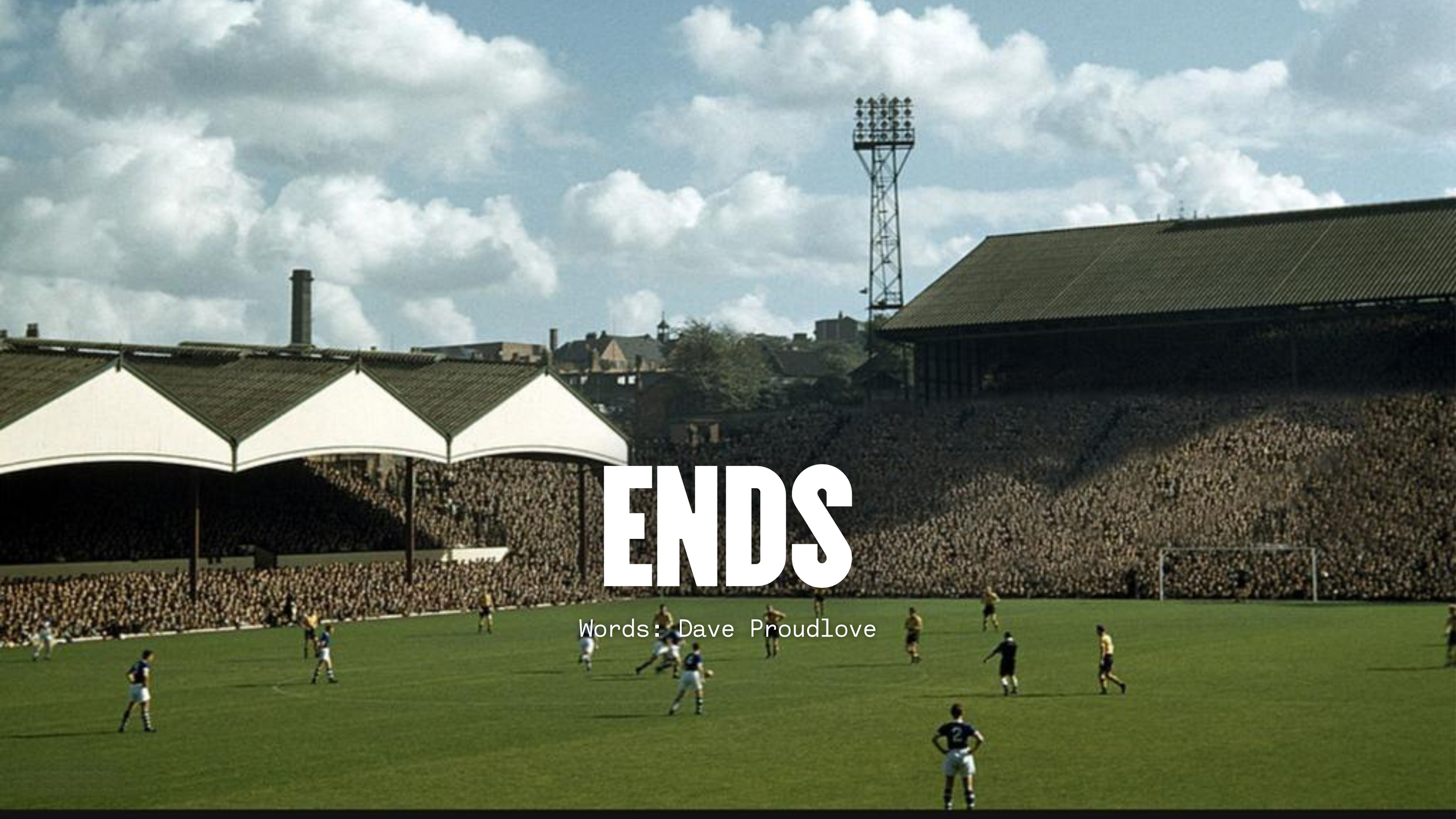

Words by Dave Proudlove | Published 19.09.2025English football has always been more than just a game. For many years it has been a culture, a way of life, and in many ways, a religion for millions of supporters. Among the many elements that have defined the English game, none were more iconic or evocative than the terraces. These were the great swathes of concrete steps, usually located behind the goals – the ends – where thousands upon thousands of supporters would stand, packed shoulder-to-shoulder, to roar on their teams. For generations of football fans, terraces were the heartbeat of the matchday experience. They were the spaces where chants and songs were born, identities forged, and where clubs became inextricably bound to the communities that supported them.

The terrace was not merely a viewing platform or a space to watch the match from; it was a stage for working class expression, a place where the game’s raw energy was magnified, the pulpit of the “folk cathedrals of modern Britain.” To understand English football in its truest historical sense, one must understand the terraces: their rise, their defining characteristics, their iconic forms, and their ultimate demise in the wake of safety concerns and tragedy.

Football’s professional roots in the late 19th century coincided with the growth of industrial towns and cities. Clubs sprang up in towns where factories and pits dominated working life, and the game quickly became the primary leisure outlet for the working class. Initially, grounds were fairly basic affairs, little more than grassed pitches surrounded by fences with perhaps a wooden stand for wealthier spectators. But as crowds swelled in the early 20th century, clubs needed to find ways to accommodate thousands of paying supporters at a relatively low cost. The solution was the terrace: rows of shallow concrete or earthen steps that allowed huge numbers of fans to stand while still being able to see the pitch. Terraces could hold tens of thousands of people. They were cheap to build, and they generated significant revenue. But beyond the economics, terraces created a new kind of atmosphere. When thousands of voices were compressed into one swaying mass, their singing, chanting, and cheering became overwhelming. The very architecture of terraces encouraged collective expression, and thus fan culture was born on the terraces.

My own footballing love affair began on one of those great terraces, the Boothen End at Stoke City’s Victoria Ground. On 28 October 1981, I paid my first visit to Stoke’s old home with my dad to see the Potters face Manchester City in the second leg of a League Cup second round tie. Stoke had lost the first leg at Maine Road 2-0, and almost made up for it at the Victoria Ground winning 2-0 to level things up. However, it ended in a penalty shootout which Manchester City won; my school night turned into a very late school night. But the football and the result were almost secondary, though Lee Chapman spooning a penalty 10 feet over the bar was quite memorable. It was the experience that really counted – the sights, the sounds, the smells – and it has stayed with me ever since and always will. I have tried to capture that night and what it means to me in the first article that I wrote for the Stoke City fanzine Duck and in my book When the Circus Leaves Town: What Happens When Football Leaves Home, but I’ve never really thought that I’ve done it proper justice. Instead, I’ll point you in the direction of the words of Sir Bobby Robson who really did encapsulate what happened to me that chilly autumn night:

“What is a club in any case? Not the buildings or the directors or the people who are paid to represent it. It’s not the television contracts, get-out clauses, marketing departments or executive boxes. It’s the noise, the passion, the feeling of belonging, the pride in your city. It’s a small boy clambering up stadium steps for the very first time, gripping his father’s hand, gawping at that hallowed stretch of turf beneath him and, without being able to do a thing about it, falling in love.”

The Boothen End was a very special place. It was one of the loudest, most intimidating home ends in the country, that – even when it wasn’t full – generated a thunderous noise that often unsettled visiting teams. The Victoria Ground was always seen as a difficult place to visit, and the Boothen End played a big part in it. From that first visit at the end of October 1981, I saw countless games at the Vic, and – aside from the occasional game in the seats and a couple of matches in the Butler Street Paddock – I watched them from the Boothen End. And I was there at the very end when the club was heading for the Britannia Stadium. On 5 May 1997, Stoke faced old Staffordshire rivals West Bromwich Albion, their final match at the Victoria Ground. By this point, the old place was tired, and the response to the Taylor Report had reduced the ground’s capacity to around the 23,000 mark. But the Boothen End was still alive, and at the time, was the biggest terrace still in use in England. It was full to the rafters that day, and we made a right old row as we watched the Potters sign-off at the Vic with a 2-1 win over the Baggies, a result that was almost customary back then.

My dad, a few of our friends and me hung around for a little while after the game, as Lou Macari waved goodbye – it was his final match in charge at Stoke – and the players did a post-match lap of honour. I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but the change that was coming was an enormous one in many ways, and not just for the club. For me, watching Stoke City has never really been the same since, despite those heady days in the Premier League under Tony Pulis and Mark Hughes.

The Boothen End, Victoria Ground, Stoke.

Photo Credit: Homes of FootballNo figure looms larger over the early development of football terraces and stadiums than Archibald Leitch, the Scottish engineer and architect whose designs came to define the look of English football grounds for much of the 20th century. Originally trained as an industrial architect, Leitch applied his knowledge of engineering and crowd management to the rapidly growing sport, cutting his teeth at Ibrox, the home of Rangers and the club he supported, though it was to be an early disaster there which drove Leitch to become the great innovator he was. Between 1899 and the 1930s, Leitch was responsible for designing or redeveloping more than 20 major football grounds, including Anfield, Old Trafford, Stamford Bridge, Goodison Park, Highbury, Craven Cottage, Fratton Park, and Villa Park. His work extended far beyond England, but it was in English football that his legacy became most pronounced.

Leitch’s trademark features included distinctive crisscross steel balustrades (or ‘lattice’) and functional, industrial-style grandstands. But he was also instrumental in the design of vast terraces. His knowledge of how to funnel, organise, and contain thousands of spectators was revolutionary in an era when football crowds were swelling beyond anything previously imagined. The Kop at Anfield, for example, though developed and expanded over time, bore Leitch’s influence in its early form. His hand was also evident at Villa Park’s Holte End, Old Trafford’s Stretford End, and numerous other ends that became synonymous with terrace culture.

Though his designs were pragmatic rather than glamorous reflecting his industrial engineering roots, they provided the backbone for the growth of English football. Leitch essentially created the template for the great football terraces: huge, sloping embankments, often covered at the rear by corrugated iron roofing, where thousands could gather in close quarters. His work gave the terraces both their scale and their character, shaping the collective experience of fans for generations.

Perhaps the most iconic of all English ends was the Spion Kop at Anfield, home of Liverpool. Built in 1906, the terrace was named after a hill in South Africa where many local men had died in the Boer War. The original Kop, influenced by Leitch’s design principles, could hold in excess of 20,000 standing supporters at its peak, making it one of the largest single terraces in the world. The Kop quickly became legendary for its atmosphere, and what made it unique was the unity of its support. While terraces across the country had their own vibrant cultures, the Kop became famous for its organised, passionate singing. Songs like ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ were not merely sung, they were belted out with an emotional resonance that could lift the team and intimidate opponents. The Kop popularised the idea of football chanting as a communal art form, with witty retorts, their own terrace anthems, and spontaneous outbursts blending into a constant wall of sound, which has often come into its own and dragged their team over the line on big European nights. Archibald Leitch’s functional terrace provided the physical platform; but it was the Liverpool support that transformed it into a cultural space. Visiting players and managers have often spoke of the Kop’s power, even now it’s an all-seated stand. Bill Shankly, Liverpool’s legendary manager, described it as his “12th man,” and that has proven to be the case since on many occasions.

The Kop, Anfield, Liverpool.

Photo Credit: Tracy WooseyIf the Kop was Liverpool’s fortress, then the Stretford End is their great rivals Manchester United’s answer. Located at the western end of Old Trafford, it has become synonymous with the loudest and most passionate of United’s supporters, and had a capacity of around 20,000. Leitch designed a masterplan to which Old Trafford was developed in 1910, and though much of the ground was altered after wartime damage and subsequent redevelopment, the principles of mass terracing he pioneered continued to shape the Stretford End.

Supporters in the Stretford End took pride in their ability to lift the team, particularly during difficult times. In the wake of the Munich air disaster in 1958 when United lost much of their playing squad, the resilience of the club’s terrace culture helped sustain them. The Stretford End became a theatre of dreams for fans as much as the pitch did for players, and even though the old terrace has since been replaced by a two-tier stand holding 14,000 supporters, it is still the place that the majority of Manchester United’s more vocal supporters gravitate to.

The Stretford End, Old Trafford, Manchester.

Photo Credit: Manchester Evening NewsAston Villa’s Holte End, another terrace that owed its scale and form to Leitch’s early 20th century work at Villa Park, was once the largest single-end terrace in Europe. Holding more than 20,000 supporters, it was a sea of claret and blue humanity, its roar echoing across Birmingham. The Holte End was renowned for humour as well as passion; terrace wit – sometimes cruel, often brilliant – was an essential part of English football culture and still is, and Villa’s supporters excelled in it.

But the Holte End was also an architectural marvel, a product of Leitch’s foresight in building stadiums that could accommodate football’s mass appeal. And like the Kop and the Stretford End, the Holte End was repurposed as a seated stand following the Taylor Report, but it still serves its purpose as the ‘Villa End.’

The Holte End, Villa Park, Birmingham.

Photo Credit: American Fine ArtChelsea’s Shed End at Stamford Bridge, Arsenal’s North Bank at Highbury, and numerous other terraces also bore Leitch’s stamp. Stamford Bridge, in particular, was one of his early masterpieces, opened in 1905 with terracing around much of the ground. Highbury’s later redevelopment incorporated Leitch’s work before Herbert Chapman’s influence gave the stadium its famous art deco look.

The Shed became Chelsea’s most boisterous area, while Arsenal’s North Bank – underpinned by Leitch’s terrace design – became a stronghold of Gunners support. These terraces, though later altered – and in the case of the North Bank, swept away when Arsenal headed for the Emirates Stadium – were part of the architectural lineage established by Leitch, who can rightly be described as the father of the football terrace.

One of the most remarkable terraces could be found at Molineux, the home of Wolverhampton Wanderers. The South Bank was another vast end that once held around 30,000 supporters, which made it one of the biggest terraces in the world. But the South Bank wasn’t a home end; it hosted both home and away fans, and during the period that hooliganism was at its height, it had a ‘no man’s land’ down the middle, designed to segregate rival supporters.

But during the late 1980s revival, the South Bank became increasingly popular with the Wolves support following the building of the John Ireland Stand (now the Steve Bull Stand.) The South Bank was eventually replaced by the Jack Harris Stand – later renamed the Sir Jack Hayward Stand after the death of the club’s former owner – which opened in December 1993.

The Shed, Stamford Bridge, Chelsea.

Photo Credit: Carshalton BlueAnd the South Bank was right up there with the Kippax at Manchester City’s Maine Road in terms of scale. Originally known as the Popular Side when Maine Road first opened in 1923, it became known as the Kippax in 1956 after a roof was added. The terrace was named the Kippax after nearby Kippax Street – named after the Yorkshire town – and it stretched the length of the pitch and was the largest standing area in the country, holding up to 35,000 fans at its peak. The Kippax was noteworthy in that it was one of few home ends that wasn’t behind the goal, while it was also one of the loudest and most menacing in the country.

The terrace was extremely basic, and for Manchester derbies and other big matches, the last fifth of the Kippax was given to the away support, which generated an incredible atmosphere. As part of Manchester City’s response to the Taylor Report, the Kippax was replaced in 1994 by a three-tier stand holding 10,178 seats, and when complete, it was the highest stand in the country. But it too disappeared just a decade later when the club left Moss Side for east Manchester and the City of Manchester Stadium.

And while not on the scale of the Kippax and Maine Road, another home end running the length of the pitch can be found in the Potteries. Port Vale moved to Vale Park in 1950, a ground that was badged the ‘Wembley of the North.’ The home end at Vale Park has traditionally been the Railway Paddock, though Vale supporters also gathered at the Bycars End at the northern end of the ground behind the goal, though in recent times, this had been given over to away supporters with the traditional away end – the Hamil Road End – switching to the home support.

The Kippax, Maine Road, Manchester.

Photo Credit: Manchester City FCWhile terraces became cultural hotspots, their very scale and density also exposed the dangers of poor planning, poor crowd management and overcrowding, and lax maintenance. By the 1970s and 1980s, many of Leitch’s original structures were ageing, neglected, and ill-suited to the demands of modern safety. Tragedies such as the Ibrox disaster (1971), Bradford City fire (1985), and ultimately the Hillsborough disaster (1989) revealed major flaws in footballing infrastructure all over the country, leading to the Taylor Report and the end of terraces in the upper tiers of the game.

Yet Leitch’s legacy remains twofold. First, he gave English football its great communal spaces, the terraces that became synonymous with passion and identity and which shaped the game’s fan culture. And second, his emphasis on functionality and crowd management laid the foundations for modern stadium design, even if later tragedies demonstrated the need for stricter regulation.

In many ways, Leitch was both the architect of the terrace era and the man whose work defined its eventual limitations. His designs were products of their time – pragmatic, industrial, and built for mass gatherings – and though modern stadiums may be sleeker and safer, they lack the visceral atmosphere that Leitch’s terraces enabled. Famous English football terraces were more than architectural features; they were cultural landmarks, social spaces, and engines of atmosphere that defined the sport for over a century. From the Kop’s emotional anthems to the Shed’s aggressive intimacy, terraces embodied the passion of the English game.

And at the heart of the story was Archibald Leitch, whose vision and engineering gave form to these legendary spaces. Without him, the history of terraces would look very different. His work enabled football to grow from modest crowds into a mass spectator sport, providing the stages upon which generations of fans expressed their devotion.

Though terraces are gone from top-flight English football, their spirit endures. The names remain, the chants survive, and the memory of standing shoulder-to-shoulder in those great heaving masses continues to shape the mythology of the game. In the story of English football, terraces and ends will always be remembered as the beating heart of fan culture.