Words by Andrew Newton | Published 06.06.2025I lay on the narrow bed and stared at the ceiling. The streetlight streaming through the thin curtains, the noise of the traffic on the road outside, and the sounds of other people talking and moving around the large building prevented me sleeping. I was used to the dark and the quiet of rural County Durham, and this was my first night in the big city. That city was Bradford and I was lying in my new halls of residence; I was here to study archaeology. For the next five years, when my attention wasn’t on roundhouses, Romans, and radiocarbon, much of my time was taken up playing and watching football. Little did I know that only round the corner from where I lay, willing myself to sleep that first night, was a place where those two things so important in my life would intersect.

As I explored my new surroundings in Bradford, it didn’t take me long to stumble upon Horton Park Avenue, just around the corner from my halls of residence, which I assumed to be, correctly as it turned out, the Park Avenue in the name of Bradford (Park Avenue) AFC. It wasn’t immediately apparent to me where the football ground would have been (although I perhaps should have realised that it would be immediately adjacent to the cricket ground around the corner on Canterbury Avenue) and I still hadn’t worked this out when I was invited to play 5-a-side at a sports centre, now a gym, on Horton Park Avenue. This sports centre was built on the Park Avenue football ground, which had been home to Bradford (Park Avenue) until they folded in May 1974. Which means that I now claim this to be the biggest football ground I’ve ever played at, despite it having been mostly demolished the year I was born! Incidentally, the city of Bradford is a very interesting place in terms of the history of football, particularly if you use the term to refer to all codes of the game, in the traditional West Yorkshire manner. This history is a convoluted one.

The city’s leading clubs switched between the Association and Rugby forms of the game, and joined the Northern Union during Rugby’s ‘Great Schism’, when 22 rugby clubs in Cheshire, Lancashire, and Yorkshire split from the Rugby Football Union, mainly over the principle of ‘broken time payments’. These various switches from code to code, and the fallings out that this caused, eventually led to the establishment of the modern clubs of Manningham RFC, Bradford City AFC, Bradford (Park Avenue) AFC, and Bradford Northern RLFC, now known as Bradford Bulls. In addition to this, the Barbarian Football Club, the famous Rugby Union invitational team, was founded in the city’s Leuchters Restaurant in 1890.

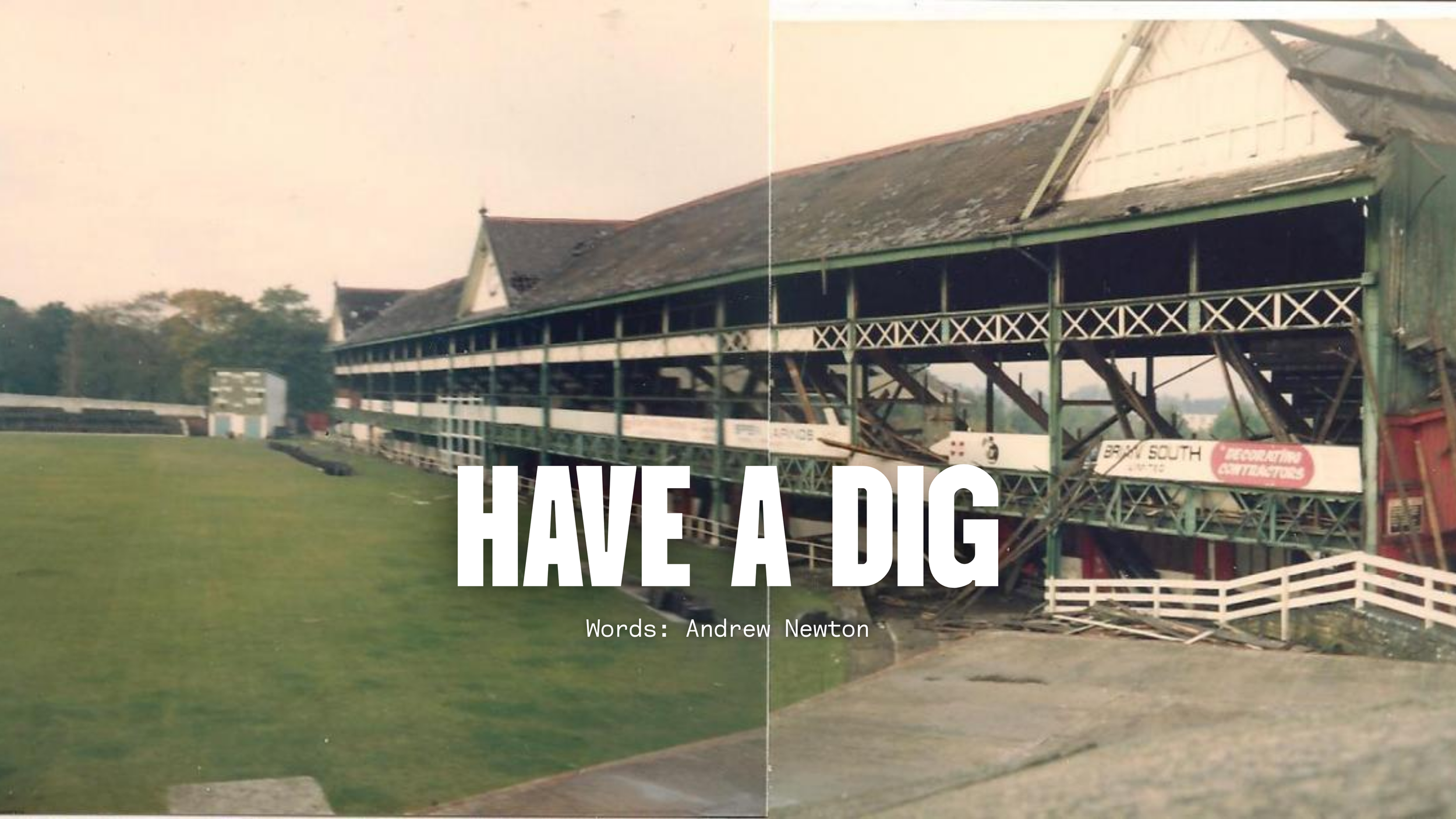

Bradford (Park Avenue) AFC’s Park Avenue ground.

Photo Credit: The Telegraph and ArgusIt wasn’t until sometime later, after chatting to regulars in my local pub, the Westleigh on Laisteridge Lane, that I realised exactly where the famous old football ground had been. This aroused in me a curiosity about both the football ground and the club that played there. I was, therefore, extremely interested when, some years after I’d left Bradford, I heard that archaeological work had been conducted at Park Avenue.

In 2013, as part of a project supported by the National Football Museum, archaeologist Jason Wood and artist Neville Gabie conducted the first ever archaeological excavation of a football goalmouth and goalpost in the world at the Park Avenue ground. Further work was carried out in 2015. A geophysical survey of the area picked up traces of the former pitch markings, indicating that repeated marking out of the pitch must have left a magnetic trace in the soil. Artefacts recovered during the project consisted of boot studs, coins, marbles, and a safety pin.

This last item relates to the occasion when the elastic in goalkeeper Chick Farr’s shorts snapped and the trainer had to carry out an emergency repair. Farr never lived this comical moment down and thereafter was regularly showered with safety pins when he stood between the posts. Parts of the remaining terraces were recorded and elements of the foundations of the two-storey grandstand, the dugouts, a turnstile, and an old toilet block were excavated.

Archaeological excavation at the Park Avenue ground.

Photo Credit: museums.euFootball and archaeology aren’t considered to be a common combination. The relevance of one to the other seems, at least, to be limited at best. There are, however, times when the two spheres meet. One of the main reasons that archaeology influences matters involving football is that much of the archaeological work conducted in the UK (and in other countries) is planning led. A change to planning law in the mid 1990s means that the impact of any planning application on archaeology has to be considered, and this applies just as much to football as it does any other sector. If a football club wishes to build or expand a stadium or training ground, the local authority’s planning archaeologist will consider if the proposed development has the potential to impact archaeological remains. If they believe that it does so, the club will be required to hire an archaeological contractor to carry out appropriate archaeological work in order for their planning application to be approved. Such decisions are made based on the known history and archaeology of the surrounding area and on other factors, such as the local geology and geography, which suggest that a location may have been suitable for human habitation in the past.

As a result, some interesting archaeological sites have been identified at football grounds. The construction of a new stand at Norwich City’s Carrow Road led to an archaeological excavation that revealed part of the prehistoric landscape in this riverside location. The pattern of deposits that were identified amounted to an island of sand, surrounded by peat. On this sandy area were scatters of worked flint, left in situ, including complete flint tools and the debris generated during their manufacture. This indicates that prehistoric people were sitting at this location, making flint tools. The types of tools that were present and the use of Optically Stimulated Luminescence, a method for dating sediments by measuring the light emitted when they are stimulated with light or heat after being exposed to ionising radiation, indicated that this activity occurred in the final Upper Palaeolithic period, between about 14,000 and 10,000 years ago.

The St Mary’s area of Southampton is known to be the location of the Anglo-Saxon port and settlement of Hamwic, from which Southampton developed. Extensive archaeological evidence of Anglo-Saxon occupation has been recorded in the St Mary’s area and so it is unsurprising that archaeological work was required ahead of the construction of Southampton FC’s St Mary’s Stadium. This work culminated in open area archaeological excavation and revealed a cemetery of late 7th century date. At this time, the Anglo-Saxons were practising furnished burial; individuals were buried with a variety of artefacts. Various theories exist about the meaning of the artefacts that occur in Anglo-Saxon graves but it seems most likely that at least one of their functions was to act as a kind of physical biography of the individual and to be representative of their position within society. The graves at the St Mary’s Stadium site were particularly richly furnished, indicating that this cemetery contained a wealthy and powerful population with access to significant trade links.

A gold and garnet pendant from one of the Anglo-Saxon graves excavated at the site of the St Mary’s Stadium, Southampton.

Photo Credit: Wessex ArchaeologyArchaeology isn’t just about the ancient past and it doesn’t solely entail digging slowly through layers of soil. Archaeology is the scientific study of human cultures through their material remains. These material remains can include extant buildings that are still in use. Buildings archaeologists use detailed archaeological recording techniques to record standing buildings and this kind of work is usually required when planning applications involve change to, or even destruction of, listed buildings. This is carried out to ensure that a permanent record of the building in its current state exists. In some cases, significant undesignated (meaning that they don’t have listed building status) heritage buildings can be subject to this kind of work. One such example is West Ham’s Boleyn Ground where buildings archaeologists conducted a programme of Historic Building Recording as part of a planning condition associated with redevelopment of the ground following the club’s move to the London Stadium. This work involved the consultation of historic records and detailed recording of the standing structures. As important social and cultural venues, the scientific recording of football grounds in this way means that detailed technical assessments of these structures are available to anyone in the future who wishes to understand the form and development of football grounds, even after those grounds are demolished or converted to different uses.

Not all archaeological work conducted in the UK is associated with building work and other developments. Universities, community groups, and other institutions regularly conduct archaeological work purely for research purposes or simply for local interest. This is what led to the excavation at Park Avenue in Bradford. Archaeological work at other former football grounds, focussing on the grounds themselves rather than earlier remains, has been carried out for similar reasons.

Industrial archaeology, the archaeological examination of sites associated with Britain’s industrial past, is an extremely interesting and important area of archaeological research. In 2017, Archaeology Scotland realised that an investigation of the sites associated with other aspects of the lives of individuals who worked in the factories and foundries that they were excavating as part of their work in industrial archaeology would also be a fruitful area of research. As such, they implemented their ‘Playing the Past’ project, which is aimed to have people engage with and explore Scotland’s rich sporting heritage. The project specifically aimed to investigate the archaeology of football in Scotland, which is strongly linked to the country’s industrial past, in order to explore the game’s history and cultural significance. As part of this, Archaeology Scotland conducted a preliminary investigation at Cathkin Park. This is a municipal park in Glasgow which was once home of Third Lanark AC, perhaps Scotland’s most famous lost football club, and also contains the site of the second Hampden Park. The original Hampden Park was located to the west, between the Queen’s Park Recreation Ground and Hampden Terrace. This was the original home of Queen’s Park Football Club. Due to plans to build a railway line across the site, Queen’s Park left the ground in 1883 and the following year moved to a new ground that had been built a few hundred yards to the east; this is the site that lies within Cathkin Park. They played here until 1903, when they moved to their current home, the third Hampden Park, which lies approximately 460m to the south. The second Hampden was re-established as New Cathkin Park in 1904 when Third Lanark took up the lease of the football stadium. This replaced the original Cathkin Park which stood on Cathcart Road, to the north. Third Lanark stayed here until 1967, the year they went out of business.

This initial work at Cathkin Park identified foundations associated with the football ground and led to further work conducted in 2022. During this more detailed excavation, the floor surface of Third Lanark’s pavilion was identified, complete with linoleum tiles in the club’s red and white colours, and the foundations for the player’s bath were identified. In addition, fragments of china in the club’s colours, brick with red and white plaster on one side, beer bottles, and a Golden Wonder crisp packet from 1967, the year of the club’s demise, were recovered.

Between these two phases of work at Cathkin Park, Archaeology Scotland also carried out an excavation at the original Hampden Park. They were investigating a rumour that the Hampden Bowling Club was built on the site of this ground, something that was generally dismissed as it was assumed that football ground was beneath local houses. Cartographic evidence was found to suggest otherwise. The archaeological work identified the foundations of the original Hampden Park’s pavilion and what appeared to be the original ground surface of the pitch. Artefacts consistent with the 19th century date of the ground, which was in use between 1873 and 1884, were recovered.

The purpose of archaeological excavation, however, is not simply to identify the remains of buildings and to recover objects, but to understand what these items tell us about the society or culture that they represent. In this respect, one of the most interesting archaeological excavations of a British football ground was carried out at Peel Park, the former home of Accrington Stanley.

Peel Park was the home of Accrington Stanley from 1919 until the original Stanley folded in 1966, approximately 4 years after their enforced resignation from the Football League. When the club moved into the ground, there were no facilities but a series of developments occurred over the next 43 years which can be traced using historic Ordnance Survey maps, old photographs, and archived documents. Following the demise of the club, the Hotel Side Stand was destroyed by fire in 1972 and by the late 70s the ground had been completely demolished, with the exception of a small brick structure built in 1937 by the Supporters Association, and it was returned to being an open playing field. The area is now used as the playing field of the adjacent Peel Park Primary School and is the home ground of Peel Park FC of the East Lancashire League.

Accrington Stanley’s Peel Park ground.

Photo Credit: Steve’s Football StatsIn 2011, the University of Central Lancashire, in conjunction with Peel Park Primary School and BBC Sport North West, carried out a community archaeology project consisting of the excavation of portions of the Peel Park ground. Two trenches were excavated. One was positioned to target the Hotel Side Stand and the other was positioned to target the location of the Peel Park Kop at the Huncoat End, which was a standing terrace during the lifetime of the football ground. The excavation recorded elements of the structures that existed at the football ground and it was interesting to note that the catastrophic collapse of the Hotel Side Stand as a result of the 1972 fire had led to better preservation of some elements of the archaeology in this area.

The artefactual evidence clearly represented the different phases of activity that have occurred here, with it being possible to make a distinction between those associated with the use of the site as a football league ground and those from it's later uses. The team involved in this project were able to draw some interesting conclusions from these artefacts. It was anticipated that there might be clear class distinctions between the artefacts recovered from the seated Hotel Side Stand and from the standing area at the Peel Park Kop. This, however, did not occur and it was concluded that there was no justification for drawing strong distinctions between seated and standing spectators at Peel Park in either the league or non-league phases of the ground’s use. It was also clear that a broad range of ages and genders were represented in the artefactual assemblage, which was considered to contradict the widely-accepted view of pre-1990 football fans as being overwhelmingly male.

Each region of the UK has an archaeological research agenda, compiled by the senior local authority archaeologists in that region. These set out the key areas that archaeological work should seek to provide information on. Although each of these address the period since the rules of Association Football were established, the game is not regularly mentioned, if at all. The research agenda for the North East of England, which is particularly strong on the archaeology of sport, focusses mainly on the architecture of sports grounds. As has been shown by the work conducted at Peel Park, Accrington, there is more to be learnt from the archaeological excavation of former football grounds, particularly with regard to the societal aspects of football, than simply the architectural form of stadia. There is, it would appear, scope for archaeological research agendas to go further with regards to the kinds of information that could be sought from this kind of work.

Archaeological investigation also has the potential to help further our understanding of the forms in which football occurred prior to its codification by the original members of the Football Association. Early football (for want of a better term) generally appears in the public consciousness as the games played at public schools such as Eton, Harrow, and, of course, Rugby, or the medieval mob football played by huge numbers of people across vast areas on occasions such as Shrove Tuesday and New Year’s Day (several of which continue as folk traditions in places like Ashbourne, Alnwick, Jedburgh and Kirkwall,). There is, however, increasing evidence that other forms of football were played throughout the UK from the medieval period onwards.

Such games were not limited to a particular sect of society and the number of players per team and the sizes of the pitches would have been much more like modern football than the great holiday games of mob football. The rules of these games varied from place to place; some allowed handling, while others didn’t; some required the ball to be driven between two upright stakes, in others the ball had to be propelled across a line extending the width of the playing area. Depending on the form and layout of the playing area, the relevant appurtenances (i.e. goal posts, boundary marker poles, or similar) may have left an archaeological trace. However, identifying the postholes that such things may have left behind as representing the playing areas of early forms of football is likely to be difficult, from an archaeological point of view, without further evidence.

We are lucky, therefore, that Reverend Samuel Rutherford, rector of Anwoth in Kirkcudbrightshire between 1627 and 1638, wrote letters. His letters demonstrate that, on arrival in the parish, the good reverend was dismayed to find that there was a piece of ground at Mossrobin Farm, close to Anwoth Kirk where “on Sabbath afternoon the people used to play foot-ball”. After remonstrating with his parishioners, it is claimed that Rutherford had a line of stones placed across the pitch to prevent the weekly games. Having come across Rutherford’s correspondence on this subject, historian Ged O’Brien, founder of the Scottish Football Museum, and a team of archaeologists investigated the site at Mossrobin Farm earlier this year.

They identified a deliberately placed line of fourteen stones and through analysis of associated deposits were able to date the placement of them at this location to approximately the same time as Rutherford’s tenure in the parish. It would appear that this represents the playing area at which the people of Anwoth played an early form of football in the 17th century. Contrary to rather sensationalist statements made in press reports about this discovery, it does not prove that football was invented in Scotland (although alongside other evidence, such as the medieval ball found at Stirling Castle, it does help to demonstrate that football has long been popular in Scotland). It is, however, a hugely important discovery in understanding what we might refer to as the prehistory of the modern codes of football. The archaeological evidence provides support for the documentary evidence and means that, for the first time, we have the physical remains of a location at which pre-19th century games resembling modern football were played.

An aerial view of the location at which the parishioners of Anwoth played football in the 17th century. Rutherford’s line of stones is visible crossing the area.

Photo Credit: The BBCThe line of stones put in place by Reverend Rutherford to prevent his parishioners playing football.

Photo Credit: The TimesThese examples demonstrate that archaeological investigation has the potential to aid our understanding of the history of football. Archaeological building recording techniques can ensure that disused stadia are accurately and scientifically recorded for posterity before they are demolished or repurposed. Archaeological excavation and survey techniques can be used to identify the remains of lost football grounds, retrieving details about these locations that would otherwise remain lost.

One of my favourite things about archaeology is its potential to provide information that challenges existing assumptions about the past. During my career in archaeology, I have been lucky enough to be involved in several projects that have changed the ways in which certain aspects of the past are understood, ranging from the internal arrangements of a certain type of Anglo-Saxon building to the extent of the defences surrounding a 10th century town. This is what the work conducted at Accrington’s Peel Park ground has gone some way to doing, suggesting that pre-existing perceptions about the demographics of early to mid 20th century football crowds might be wrong. Archaeological investigation can improve our understanding of football and football culture in the past.

Archaeological evidence differs from documentary evidence. It consists of direct remnants of acts carried out by people, rather than the reporting and interpretation of those acts, which can carry bias. Although archaeological evidence can be manipulated and interpreted with distinct bias (my post-graduate research was about 20th century political movements using archaeological evidence to support their ideas), if used correctly it has the potential to offer an unbiased and/or slightly different perspective than documentary evidence. This means that, used in conjunction with one another, the two can offer a more rounded picture of a historical subject. This combination of different forms of evidence also has the potential to act in a complementary way, helping to identify the presence or location of physical remains, as has been demonstrated at Anwoth.

Given the social and cultural significance of football in British history, it is a little surprising that it does not feature more prominently in the regional archaeological research agendas. There is certainly significant research potential in identifying the physical remains of early forms of football and the archaeology of football stadia can add important information to our understanding of the post-medieval/early modern/industrial (the terminology varies from region to region) period. The development of football, alongside other sports, was a key social and cultural event in the industrial revolution.

Plenty of archaeologists are football fans and there seems to be a reasonable level of participation in the game. The Chartered Institute for Archaeologists organises an annual tournament and the Winckelmann Cup is a Europe-wide football competition specifically for archaeologists, named after the 18th century German archaeologist Johan Joachim Winckelmann. There is certainly a growing consciousness within the world of archaeology of football’s importance in our recent history; in 2021, the Council for British Archaeology’s magazine British Archaeology published an article about Historic England’s project to preserve elements of York City’s Bootham Crescent within the new development at the site following the club’s move to the LNER Community Stadium. This is perhaps why an increasing amount of football-related archaeological work has been carried out over the last couple of decades, alongside an increasing rejection of the perception that an interest in football is anti-intellectual.

The logo for the 2025 Winckelmann Cup, to be held in France in July.

Photo Credit: winckelmanncup.com