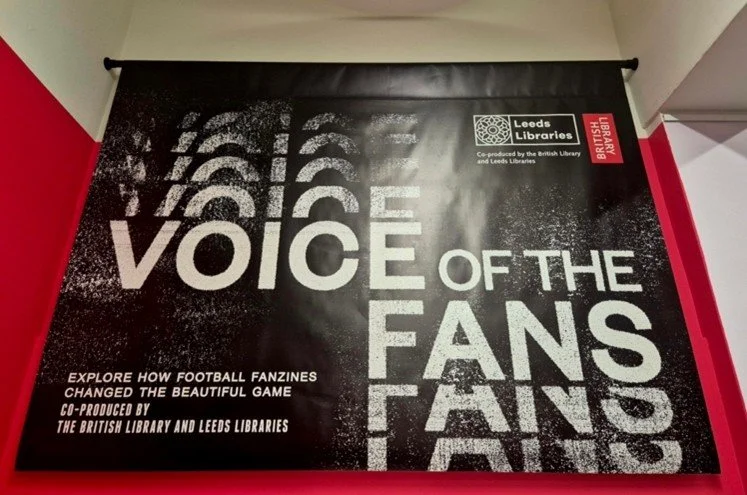

Words by Dave Proudlove | Published 25.07.2025Back in May, I was in Leeds for a conference and I got lucky in that it coincided with Leeds Central Library hosting an exhibition (co-produced by Leeds Libraries and the British Library) that piqued my interest when it was announced. ‘Voice of the Fans: Explore How Football Fanzines Changed the Beautiful Game’ presented a brief history of England’s football fanzine revolution, and was a celebration of how ordinary supporters changed the narrative in terms of how the game and those that follow it were perceived by both clubs and authorities, and included some truly brilliant examples of the genre. It left me marvelling at what the DIY ethic towards football content has achieved over the years, and also the scale of influence that a generation of fans has had over the direction of English football.

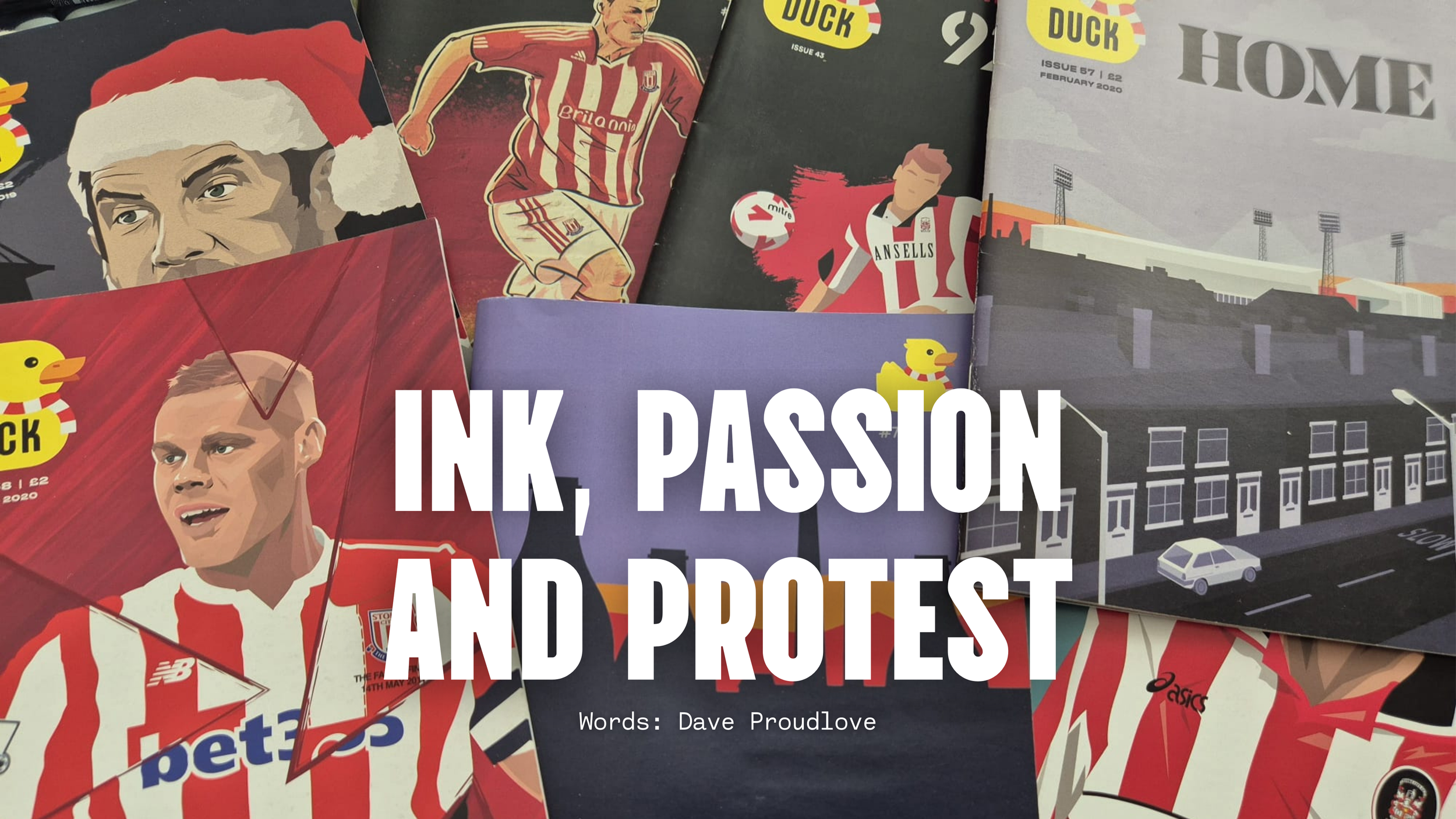

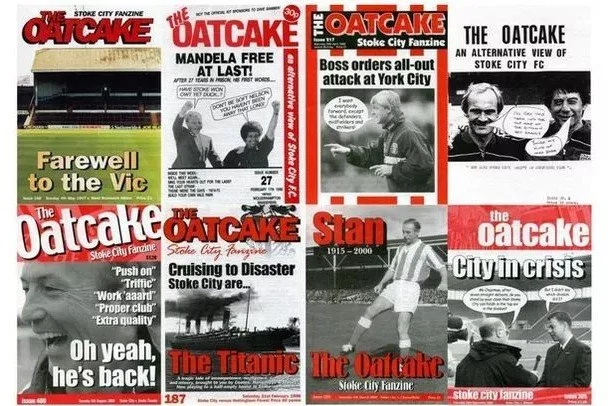

For me, the exhibition was important from a personal perspective too. I have a bit of history with football fanzines. My first experiences came from the late 1980s onwards as a serious consumer of Stoke City fanzine, The Oatcake, while I ended up writing for another, Duck.

As the exhibition in Leeds illustrated, English football has a rich fanzine heritage stretching back decades, emerging in the 1970s before exploding during the grim 1980s – when football supporters were painted as one of Thatcher’s enemies within – and flourishing from the 1990s. Fanzine culture in English football is a vivid and passionate expression of grassroots creativity, fan solidarity, and resistance to commercialisation, providing a platform for fans to voice opinions, share humour, criticise authorities, preserve historical memory, and foster community away from the constraints of official club communications and mainstream media. Though digital media has transformed the way fans interact today, the legacy and spirit of fanzines has endured, evolving rather than disappearing.

The term ‘fanzine’ is a portmanteau of ‘fan’ and ‘magazine’, typically referring to non-professional, non-commercial publications created by enthusiasts of a particular subject, in this case, football. Inspired by earlier zine cultures, particularly the punk music scene, football fanzines began to surface in England during the late 1970s as an alternative to the often dumb and beige, sanitised, corporate-friendly content in ‘official’ matchday programmes and national newspapers.

Producing a fanzine was a labour of love for their protagonists. Writers would use typewriters, glue, scissors, and photocopiers to assemble content, often from contributors across different areas. These were hand-sold outside grounds, through mail order, or swapped with fellow zine creators. This DIY ethic created a strong sense of authenticity, but also built camaraderie and solidarity across club lines; while rivalries remained fierce, fanzine writers often shared a mutual respect for one another’s labours, dedication and creativity.

One of the earliest and most influential football fanzines was When Saturday Comes, launched in 1986. Although it later developed into a professionalised monthly magazine, its early issues were a touchstone for what followed: a mix of satire, opinion, nostalgia, cartoons, and match reports, with a strong undercurrent of political awareness and social critique.

It’s an age ago now, but the 1980s were a turbulent time for English football. Attendances were falling, hooliganism was rampant, and stadium facilities were often dangerous and decaying. Fans were frequently portrayed as thugs in the mainstream media, whose coverage was more often than not sensationalist and detached from reality, and as a result, the sport itself became increasingly marginalised in cultural and political life, as illustrated by the views of Thatcher and her acolytes; witness the Sunday Times editorial in 1985 that branded football “a slum sport played in slum stadiums and increasingly watched by slum people.” In this context, fanzines emerged as a way for supporters to reclaim the narrative, giving a voice to those who were misrepresented or ignored. They were fiercely local, often blunt and irreverent, and provided a space for real fan voices to be heard. They critiqued club owners, took the piss out of rival fans, and sometimes featured content as intimate as memories of away days, obituaries, and even poetry.

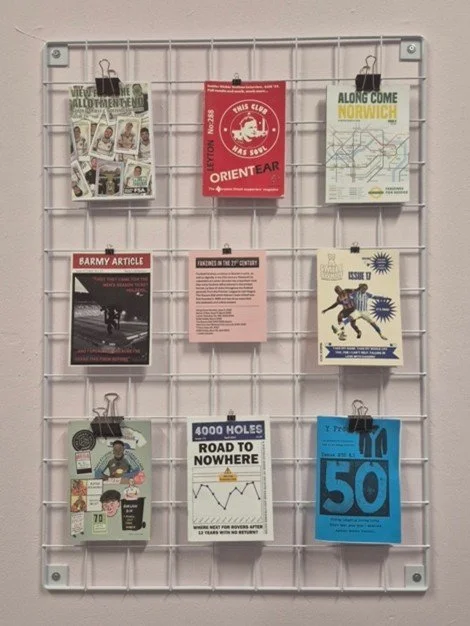

The fanzine revolution swept the country, with titles like 4,000 Holes (Blackburn Rovers), Through the Wind and the Rain (Liverpool), United We Stand (Manchester United), and Only One F In Fulham (Fulham) – which was born in the midst of the long battle to save Craven Cottage – all becoming prominent among the movement. And in the Potteries fans of Port Vale – including Nick Degg, the city’s current poet laureate – launched The Memoirs of Seth Bottomley following on from The Oatcake down the road at Stoke City. The Oatcake was my first taste of fanzine culture, and it wasn’t to be the last.

Voice of the Fans: Explore How Football Fanzines Changed the Beautiful Game – a recent exhibition at Leeds Central Library co-produced by the British Library and Leeds Libraries.Numerous fanzines were exhibited at Leeds Central LibraryStoke City were not immune to football’s malaise during the 1980s, and in 1985 dropped out of the top-flight, smashing every record going in the process. During the summer, they appointed former England captain Mick Mills as player-manager, and initially, he steadied what was a very unsteady ship. His first couple of seasons in charge saw Stoke play some decent football at times, and had supporters believing he could lead them back to the big time.

But it didn’t last. Mills was always in need of a bit more time, or another signing, and eventually the supporters became tired of his excuses and the stagnation. The Potters made an awful start to the 1988/89 season, and this was reflected in attendances which had fallen to 7-8,000. They finally notched their first win of the season in the League Cup, winning away at Leyton Orient in the first leg of the second round tie, starting a little unbeaten run. That run was ended by the Os in the second leg, who won at the Victoria Ground on the night, before winning the tie on penalties. I was there, and it was dire, the only highlight being the substitute appearance of the late, great Paul Ware, who put his more experienced team mates to shame with his energetic showing.

And that was the final straw for a small group of fans – including editor Martin Smith – who stood on the Boothen End, and The Oatcake was born, the first issue of 300 copies bashed out on a child’s typewriter and photocopied. Its DIY punk ethic was refreshing, an alternative view of the club produced by fans, for the fans. The Oatcake challenged the club and its hierarchy, and was full of gallows humour, something you needed in spades towards the end of the Mills era. This could be best summed up by the ‘suicide pills’ – they probably wouldn’t get away with that these days – provided with the issue that preceded a derby match with Port Vale “in case the unthinkable happens.” The Oatcake went on to become as much a staple of a Stokies’ matchday as the edible version, selling thousands of copies every home game. And I was one of those that needed a fix.

My first was towards the back end of 1989. I forget the game, but it was shortly after Mills was sacked and was badged a special ‘kick a man when he’s down issue’, featuring a front page ‘exclusive’ on the real reason for Mills’ dismissal: a photo of him snogging Kevin Steggles in their Ipswich Town days; Steggles was with the Vale at the time of Mills’ sacking…

Another early favourite was the Nelson Mandela issue (“have Stoke won owt yet duck?” … “dunner be soft Nelson, you anner bin away that long”) which contained one of their greatest cartoons, ‘Build your own Vale Park’, which involved taking a boot to a cardboard box and some origami with scissors and some tape.

The height of The Oatcake’s success was probably during Lou Macari’s first spell at the club. Lou built a team to be proud of, and the crowds returned to the Victoria Ground in numbers, with The Oatcake becoming a genuine institution. But while it was hugely popular, it remained fiercely independent, always presenting ‘an alternative view of Stoke City FC’ just as it did when it was launched.

The Oatcake – a staple at Stoke City for over 30 years.

Photo Credit: SOT LiveThe 1990s marked a transitional period for English football after the turmoil of the 1980s. The creation of the Premier League in 1992 ushered in a new era of commercialisation, television deals, and global audiences, which has led to the gentrification of the game. While the sport became safer and more financially lucrative for clubs, players and agents alike, many fans became alienated by the increasing corporate influence. Once again, fanzines came to the fore, becoming important vehicles for the resistance of this shift. Publications like The Mag (Newcastle United), Red Issue (Manchester United), and Keep The Faith (Leeds United) all documented issues such as rising ticket prices, all-seater stadium mandates, and a growing disconnect between club hierarchies and lifelong supporters.

At Manchester United, fanzines played a critical role during the opposition to Rupert Murdoch’s attempted takeover of the club in 1998. Red Issue and United We Stand were instrumental in organising fan-led resistance, exposing financial concerns, and distributing protest material, while they were also prominent in protesting the Glazer takeover, though with less success. Similar fan mobilisations occurred at other clubs like Wimbledon, whose fans formed AFC Wimbledon in 2002 after the theft of the club’s heritage by MK Dons.

Despite the political undertones, fanzines remained humorous and grounded in the culture of match-going fans. Regular columns featured jokes, limericks, strange anecdotes, and scathing reviews of referees and opposition fans. Cartoons and satirical takes on players, managers, and journalists continued to be a staple. Such humour quite often served as a coping mechanism, fans using laughter to deal with heartbreak, injustice, or the absurdities of modern football. In the process, fanzines became not just informative but cathartic, a release.

As the movement matured, fanzines also provided a space for underrepresented voices in football. Female fans, LGBTQ+ supporters, and people of colour began contributing content that challenged the traditional masculine, often exclusionary image of the football supporter. Zines like Girl on the Terraces and articles in the bigger, mainstream fanzines from female perspectives pushed back against the stereotype that football was solely a man’s world. They challenged sexist chants, celebrated female fandom, and campaigned for a more inclusive matchday experience. Anti-racist campaigns like Kick It Out found allies in fanzine writers, and many articles calling out racist behaviour in the stands or discriminatory policies by clubs appeared in many zines around the country. Fanzines also continued to tackle broader political themes, including critiques of Thatcherism, police treatment of fans, and issues such as class inequality and housing around stadium redevelopment projects, which became increasingly common during the 1990s and 2000s following the publication of the Taylor Report.

However, by the early 2000s the rise of the Internet was posing an existential challenge to the printed word. Message boards, blogs, forums, and later social media platforms like Twitter and YouTube changed how fans produced and consumed content. As a result, numerous fanzines either moved online, or shut down entirely.

The mighty, and much missed Duck.Over time, websites such as Arseblog (Arsenal), The Anfield Wrap (Liverpool), and True Faith (Newcastle United) began as online extensions of fanzines or were inspired by them, and these sites retained the independent, fan-driven ethos of printed zines but reached much larger, often global audiences.

While many lamented the loss of physical copies, the digital shift allowed for greater immediacy and multimedia engagement. Podcasts, vlogs, and online zines became the new frontier of football fan expression. When Martin Smith announced that The Oatcake was calling it a day in 2019, I was genuinely saddened. The Oatcake was a big part of my youth and following Stoke, but I understood. It’s truly miraculous that it survived as long as it did – 31 years – particularly given the technological shift enabled by the Internet, something that Martin acknowledged as a contributory factor. But after spending many years being editor of a matchday programme with a non-league football club, I empathised with the stresses that go with meeting a production deadline – a new issue of The Oatcake was produced for every home game; Martin and his team had earned their break.

However, some were trying to buck the trend. By this point I’d become a regular contributor to a Stoke City magazine that was very much rooted in fanzine sensibilities. Duck was launched in 2013 by Anthony Bunn and Lee Hawthorne, their aspiration to produce a zine that they would want to buy themselves. It was a little different from the traditional fanzine in that it was glossy and contained advertisements, but it was a damn fine product, featuring some excellent fan produced content, and guest writers. And it didn’t just cover Stoke City and football; music, fashion, and art all popped up in the pages of Duck.

I once produced a review of a Rolling Stones gig at Old Trafford. As well as putting out first class content, the Duck team were about far more; they were deeply committed to North Staffordshire and went out of their way to support local charities and good causes, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, distributed free electronic copies of the magazine far and wide. Sadly, it was probably the pandemic that put Duck into end days territory. When football returned it was behind closed doors which impacted hugely on circulation, and when the gates were finally opened again, the matchday habits of many changed. After 78 issues and ten years, Duck was no more. It was another sad loss.

Others try to strike a balance and continue to maintain hybrid models, publishing a few print issues per season while engaging online between matches; the medium may have changed, but the values of DIY publishing, fan independence, and community criticism live on. But while new technology has provided a significant challenge, some traditional fanzines have persisted into the digital age.

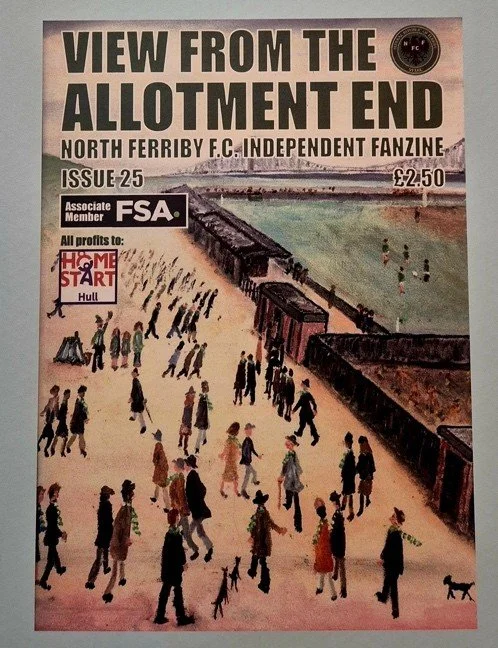

While it does have a strong online presence, When Saturday Comes remains in print and continues to be popular throughout the football community. But one of the best around can be found in the non-league game. Fans of North Ferriby who compete in the Northern Premier League Division One East continue to put out View from the Allotment End to great acclaim. One of their most memorable issues saw them create their own version of L.S. Lowry’s ‘Going to the Match’ which adorned the cover of issue 25, a copy of which formed part of the Leeds exhibition.

View from the Allotment continues to survive despite the challenges thrown up by the Internet.As the recent exhibition at Leeds Central Library demonstrated, fanzines have now become valuable historical documents, and university archives and museums like the National Football Museum in Manchester have begun collecting and preserving old zines, their value and importance recognised through their unique, grassroots perspective on football history, culture, and society, which can educate newer fans about their clubs’ heritage, struggles, and fan heroes beyond what’s found in official narratives.

And while times have changed, the original fanzine spirit and passion for protest is still alive and well. In recent times, modern fanzines have been central to fan protests and mobilisations. During the 2021 European Super League debacle, fanzine writers were among the first to mobilise opposition. Manchester United’s United We Stand, the Chelsea fanzine The Blue and White, and others produced impassioned defences of football’s traditions and supporter rights, while fan-led movements like Spirit of Shankly at Liverpool and The 1894 Group at Manchester City often collaborate with or have emerged from fanzine communities.

It is perhaps quite apt that Football Heritage is running an article about England’s football fanzine culture. While Football Heritage has emerged as an online project, it is very much rooted in fanzine values, with a strong DIY ethic that is the hallmark of fanzine ethos. For me, it is very much a continuation of the tradition, and I’m proud to be a part of it.

Fanzine culture in English football is a testament to the creativity, passion, and resilience of supporters. Born out of frustration with officialdom and footballing hierarchies, and a desire for authenticity, fanzines created a unique space for fan voices to thrive and gain influence. Through critique, nostalgia, humour, and activism, the fanzine movement has influenced how football is experienced, understood, and remembered.

While the medium may have shifted in the digital age, the spirit of the fanzine endures. As football continues to evolve, so too will the methods by which fans assert their presence. Whether in photocopied publications put together on the kitchen table and handed out outside grounds, or digital blogs shared worldwide, fanzine culture remains a powerful reminder that football is, and should always be, for the fans.

All images by Dave Proudlove unless otherwise stated.