Words by Göker Giresunlu | Published 07.05.2025In the 2023-2024 season Bayer Leverkusen, a club originally founded as a gymnastics club by Bayer factory workers in the early 1900s, stunned football by suffering just one defeat all season, winning the German Bundesliga and DFB Pokal and reaching the UEFA Europa League final. Demir Çelik Karabükspor, or Kardemir Karabükspor as it is now known, was founded in 1938 as a gymnastics club by workers at a state-owned iron and steel factory in Turkey. Despite sharing a similar origin story, the club does not share a similar fate to Bayer Leverkusen because it completely collapsed in 2018, after peaking in the same decade. From the local amateur league to the Turkish top flight, and even the Europa League playoffs, this is the story of a modest but significant football club.

Life in the small and remote Turkish village of Karabük changed dramatically when the state decided to build a huge iron and steel production complex on the banks of the river that ran alongside it. Thousands of people, including British engineers and workers, began to either live around the factory or commute there on a daily basis. It was not an ideal place to live. The village was turning into a town, and then a city, but it had no previous social infrastructure. Two things came to the aid of the workers who were destitute in the face of long working hours and harsh living conditions: cinema and football. A love for football was perhaps one of the few things that British and Turkish colleagues of the factory had in common. Demir Çelik Youth Club was born out of these conditions as the factory’s amateur football club in 1938, then merged with the city’s second football club Karabük Youth Club in 1969 and became a professional football club. Over the decades, the club's fortunes have mirrored those of the city, with the exception of the glorious decade of the 2010s, which ended in its complete collapse.

At a time when football in Turkey was largely an amateur affair, Demir Çelik was well-placed thanks to the financial backing of the state-owned iron and steel works. The club's first modern stadium was built in 1958 and held more than 4.000 spectators when the city’s population was only around 30.000. It probably transferred players illegally by employing them in the factory. However, this advantage was not sufficient to win competitions. They were up against Zonguldak Kömürspor, the club of state-owned coal enterprises, which had a larger population and greater financial resources. Zonguldak was also the administrative center of the district. For years, Demir Çelik and its fans believed that they were being discriminated against in the local amateur league. The expectations were quite high, but performance was not enough. They only won the local league once in the early 1940s and were often eliminated by Kömürspor or other Zonguldak teams in many instances. The club was heavily criticized by locals and the press for their lack of success.

However, the club was still beloved, as it was a symbol, a representative of a city that was made up of migrant workers only two decades prior. Demir Çelik’s fierce competition with Zonguldak led to many conflicts, including bloody fights and decisions to abandon the league. In fact, Demir Çelik abandoned the league one season when it was the favorite to win it, and the local press fully supported this decision. This was a period when Karabük was growing as a city and trying to throw off the “yoke of Zonguldak” as an administrative center. Demir Çelik emerged as the symbol of this movement. But it was not loved without conflict. Another team, Karabük Gençlik, was founded in the early 1950s and represented the other side of the city. While the factory workers and their families supported Demir Çelik, many other residents who felt discriminated from the privileges of being a factory member supported Karabük Gençlik. The games between them were mostly violent, as evidenced by the number of injuries taking place in each game.

Kardemir Karabükspor in their infancy.

Photo Credit: Independent TürkçeWhen professionalism became the trend in Turkey in the 1960s, Karabük also wanted to jump on the train, but they arrived late, partially because of this conflict. In 1969, Demir Çelik was founded after months of in-depth discussions on how to run the club. The Karabük Gençlik side rejected the idea of a factory-dominated management and club, while the factory side tried to put its weight into the management. The club was set up in a unique way, in which the directors’ board consisted of five representatives from the city and five representatives from the factory. The problems ensued when they had to find a president and arrange a legal and formal way to finance the club. The club spent decades in the lower divisions of Turkish football until a surprise promotion to the First Division in 1993. The final months of their first season in the First Division witnessed one of the most dramatic events in Turkish football history.

State enterprises were considered among one of the main reasons for Turkey’s economic problems in the 1980s, which led right-wing governments to consider closures and privatization in various industries. The profitability of Karabük Iron and Steel Factories was also part of the debate. As Karabükspor struggled to find its way in the first division, the factory, which was responsible for the social and economic life of the town, was under threat of closure. Karabükspor finished the first half of the season at the bottom of the table with just one win in 15 games. However, the team's performance improved in the second half of the season, while the threat of survival continued to grow. The rise of Karabükspor, a modest team from a modest town, attracted sympathy across the country, especially when people thought they were going to achieve the impossible by avoiding relegation. That sympathy grew to an astonishing degree when Prime Minister Tansu Ciller announced on 5 April that the closure of the Karabük Iron and Steel Factories was one of the government's priorities.

In Karabük, the fight against relegation and the fight against neoliberalism went hand in hand. After three or four decades, Karabükspor regained its symbolic importance in the city's political and economic struggles. This, and the people's decision to resist closure or privatization, became crystal clear when the players took to the pitch with a banner that read: "The closure of Karabük Iron and Steel Factories is a social and economic murder". When Karabükspor drew with Galatasaray and won against Beşiktaş early in the second half of the season, the newspapers hinted at the possibility of a miracle escape from closure and relegation which attracted many other onlookers in the country. When the Turkish Football Federation decided that the game between Karabükspor and Sarıyer would be played in Bursa instead of Karabük, thousands of Bursaspor fans came to support Karabükspor.

When a reporter asked the home-grown Levent Açıkgöz how he felt after the win over relegation rivals Sarıyer, Levent was clear: “What can I say? We are happy. Nobody can touch or harm Karabük”. The following week, Karabükspor played Bursaspor in Bursa. Interestingly, the Bursaspor fans supported Karabükspor against their team. Every Karabükspor player explicitly said that they would either die there or win. When they won 4-0, thousands of Bursaspor fans celebrated with them. Tarik Yurttaş, another home-grown player, responded in the post-match interview to those who mocked Karabük for being a small town that resembled a village: “Let them come and see if Karabük is a village or not. We respect them no matter what they say, but they have to respect Karabük too”. Karabük had become more than a town or a city at that point. It was a feeling, a culture and a movement.

The Karabükspor side of 1993-94.

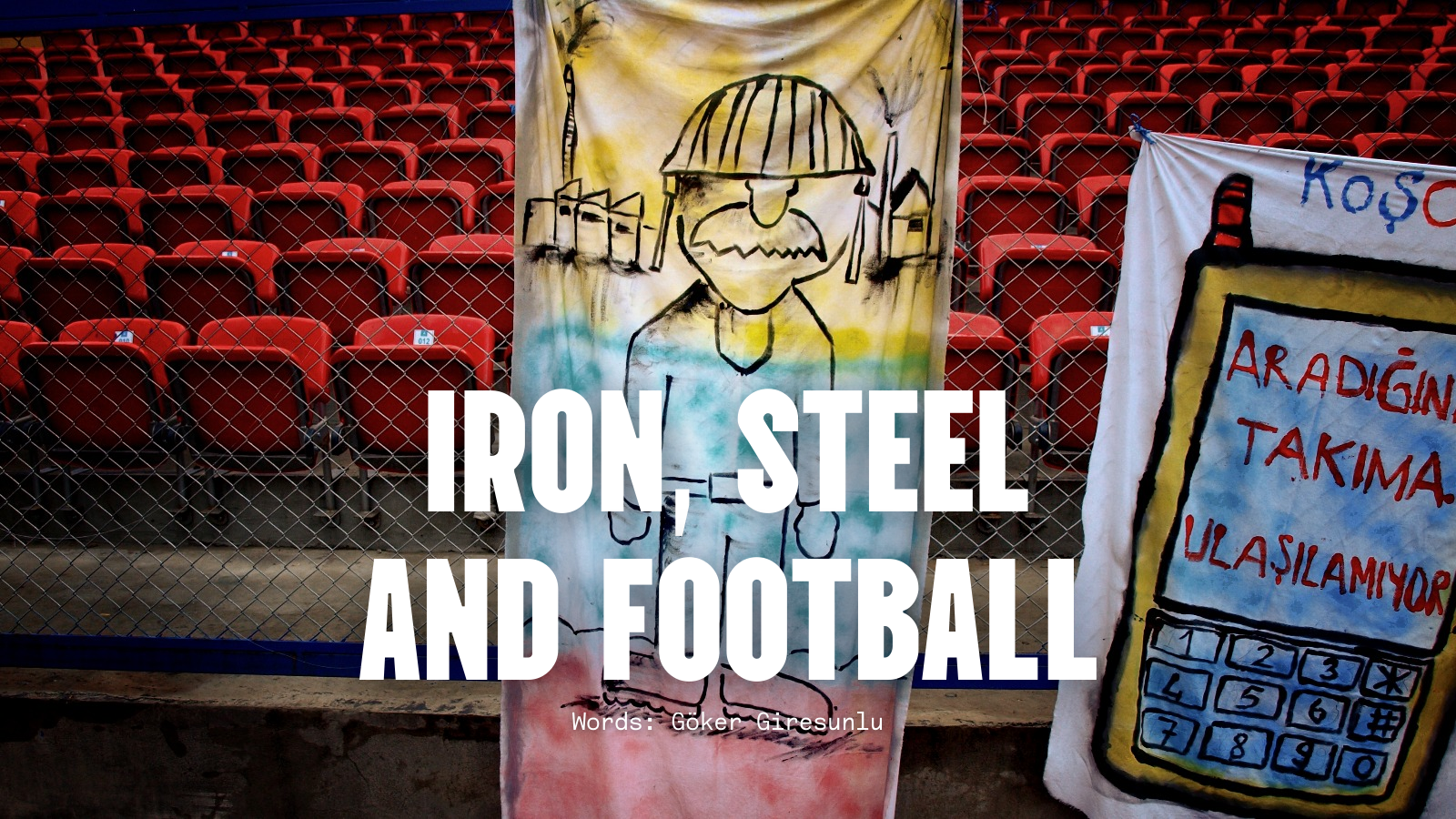

Photo Credit: 10 HaberThis feeling reached its euphoria in the final week of the season when Karabükspor faced Zeytinburnuspor, a team standing just above them at the league table. A draw would have been enough for Karabükspor to stay in the league. The people were confident but nervous about the game. Many of them arrived at the stadium early in the morning to find a seat. People from other cities, such as Ankara and Bursa, who support their local teams, came to Karabük at night and stayed overnight around the stadium to support Karabükspor. However, many of them could not find a place to sit because of the crowd. The stands were filled with people and decorated with banners from fan groups and unions. In particular, the banners of the trade unions implied that the closure of the factories would be a betrayal of the country and the city. One of them addressed the late Atatürk, the founding father of Turkey, and said: “Protecting the Republic and the factories that you entrusted to us is a duty of honor”.

Joy and euphoria gave way to fear when Kemal Yıldırım scored for Zeytinburnuspor in the 31st minute. The overconfidence in Karabük was replaced by an extraordinary sense of fear, anger, and hopelessness in the stands. On the pitch, however, the team performed well. Especially in the second half, Karabükspor created many chances. When Nejat had a good shot that looked like it was going in, everyone in the stadium went crazy, but it turned out to be the other side of the net. The game was an emotional rollercoaster. A few minutes later, in the 74th minute, Hasan scored the equalizer and the stadium erupted. Just 15 minutes without conceding a goal would have meant everything to Karabük. But in the 90th minute, a header from an ill-judged cross found the back of the net to seal Karabükspor’s relegation. The stadium fell silent. Yurttaş later said that the referee told him to pick up the ball quickly and score. Even the referee tried to bring Karabük back to life, but it was impossible. When the game was over, some players and supporters remained silent for hours, while others tried to start fights. Yurttaş said he felt the city could not breathe after the game, as if someone had cut its veins.

Although the battle against relegation was in vain, the battle against closure achieved a partial victory after months of resistance. On 8 November, not only the factory, but the whole city of Karabük went on a strike against the closure. Political parties closed their offices and covered their signboards with black sheets to prove that this was about more than political competition. Parents did not send their children to the schools, and shopkeepers did not open their doors. They also closed the tunnel, which was the only way into the city at the time. This organized resistance led to a compromise. The government privatized the factory and sold the shares to the workers, businessmen, and other people of Karabük. The following years were a time of transition for both the town and the team. Karabükspor spent two years in the first division between 1997 and 1999, but local politics and rivalry between the unions dampened the enthusiasm around the club.

The enthusiasm came back when a modest group of players won promotion to the Super League with a record-breaking run in the second division in 2009-2010. Emmanuel Emenike, who would later play for Fenerbahçe and West Ham, was the gem of the team. He was joined the following season by Florin Cernat. Karabükspor spent five consecutive seasons in the Turkish Super League. In 2012-2013, the club faced both relegation and European qualification in the same season. In 2013-2014 it managed to secure a European spot. In the 2014-2015 Europa League qualifying round, Karabükspor surprised everyone by eliminating Rosenborg. In the playoffs, it faced a great St Etienne side and took them to penalties with some great defending on the road. However, a poor performance in the shootout meant elimination for Karabükspor, which was compounded by relegation in the same season. Despite spending just one year in the second tier and returning to the Super League with a last-day win over Göztepe to secure second place in the table, the 2015 relegation was the beginning of the end. In 2016-2017, former Juventus defender Igor Tudor was brought in as manager and enjoyed a good spell in charge, with Karabükspor's style of play winning over fans and other football enthusiasts. However, he left for Galatasaray, and the club’s financial problems began to show.

Karabükspor before making their continental debut.

Photo Credit: Kirmizimavi.orgWhen Karabükspor sold Emenike to Fenerbahce for €9 million in 2011, the club's fans and presidents boasted that the club had no debts. The factory and the union were still the club's main sponsors, and all the successes of recent years had been achieved on a modest budget. At the same time, the club was starting to renovate its stadium. Everything seemed perfect. In 2017, however, the picture was completely different. The club was in a financial crisis, with debts of over 150 million Turkish Liras predicted. After a summer of mediocre transfers, Karabükspor was relegated in 2018 after winning just three and drawing three during the season. At the same time, the Karabük Republican Public Prosecutor's Office prepared a report, which Atilla Türker revealed in his article. Apparently, the club spent millions of liras on player management companies, from which the club never transferred any players. Some expenses, such as "player scouting expenses", were left vague in the club's financial accounts. Some other expenses had no invoices. More interestingly, the report states that a former employee of the club, who worked as a general coordinator, continued to use the club's official signature for a long time. In 2020, Türker wrote a new article about Karabükspor. The article revealed that many former presidents and board members of the club had been implicated in corruption in an ongoing court case. For example, certain personal expenses, such as clothes for the president's wife, were charged to the club. In addition, certain players were paid much more than they were valued or paid by their previous clubs.

This corruption led to Karabükspor's complete collapse. The club was relegated in successive seasons, with the exception of one year when relegation was frozen due to the pandemic, with negative results due to the use of inexperienced youth team players due to a transfer ban. Eventually, the club was relegated from the Regional Amateur League, in which it did not even participate, to the lowest division. Today, the club exists on paper but does not play in any league at any level. A businessman called Adem Aydım took over a local amateur club and changed its name to Karabük İdman Yurdu. The club was promoted to the third division in 2022-2023 and has stayed there this season. So, there is hope for a phoenix club in the city. However, the factory is reluctant to support the club financially, and local politicians are not too concerned about the situation. As a result, it is very possible that the phoenix project could collapse at any moment.

Though they are on the rise again as Karabük İdman Yurdu, they have work to do to stop the future of football in Karabük looking so bleak.

Karabükspor in action.

Photo Credit: Kirmizimavi.orgEndnotes

For a detailed account of Demir Çelik Karabükspor’s political significance in local politics during 1950s please see: Göker Giresunlu and Can Nacar, “‘Her Zaman Siz Dayak Yersiniz, Bu Sefer de Siz Vurun’: 1950’lerde Karabük-Zonguldak Rekabetini Futbol Üzerinden Okumak,” Tarih ve Toplum: Yeni Yaklaşımlar, no. 22 (Fall 2023): 152–75.

There are clear divergences in the clubs’ name throughout history; while the former is literally called Iron-Steel Youth Club, referencing the name of the factory, other is called by the name of the city.

Quotes from banners and interviews in the article are from the documentary 15mayıs94, produced and published by Kırmızı Mavi Karabük Sports Culture Association in 2017. This is a must-watch documentary about Karabükspor’s venture in 1993-1994 season. “15mayıs94: Ve şehir kapkara suskunluğa bürünür” (15mayıs94: The day when the city fell into silence), May 15, 2017, Kırmızı Mavi Karabük Spor Kültürü Derneği, https://youtu.be/GdsmAx0kRhM?si=UnbBiERz9IsFICRg.

Turkish First Division is called Turkish Super League since 2001-2002 season. I refer to the league accordingly as First Division for seasons before 2001, and as Super League for seasons after 2001.