Words by Miguel Sanchez | Published 17.09.2025In June 1967, after 18 league games with only four to play (with two points awarded for a win), KF Tirana were leading the Albanian league with 33 points, two ahead of KS Dinamo Tirana and eight ahead of KF Partizani Tirana, their opponents on Matchday 19.

Needless to say, this was a decisive derby in the title race.

While Dinamo were hoping that Tirana would slip up, Tirana were looking to secure their third consecutive title after clinching the 1964/65 and 1965/66 championships. To find their titles before then, you had to go back as far as 1937 - three decades of significant change in Albania, both politically and in football. Firstly, KF Tirana was no longer called that, but 17 Nëntori (17 November), a reference to the date on which the partisans liberated Tirana from German occupation in 1944.

The problem was that the Albanian communist dictatorship, which had forced the name change, had its own plans for the outcome of the 1966/67 season: to prevent 17 Nëntori from becoming champions. To do this, Partizani (a team linked to the army) had to win their derby against 17 Nëntori, and then the entire state machine would ensure that Dinamo (linked to the Ministry of Internal Affairs) would eventually win the championship. Unsurprisingly, the match between 17 Nëntori and Partizani was a tense one, and when 17 Nëntori's Bahri Ishka scored to make it 2-1 with a few minutes to go, several players got into a brawl which escalated when the referee decided to call the game off. In the end, 17 Nëntori won and, to make matters worse, Dinamo were held to a goalless draw by KF Vllaznia.

Those results apparently betrayed the dictatorship's hopes, but it eventually found a solution. A few days after 17 Nëntori-Partizani, the Federation (at the behest of the regime) announced that both teams were excluded from the competition, due to the unsporting behaviour exhibited at the end of that match. The 2-1 result turned into a 0-3 defeat for both teams, and neither team played their remaining matches, with the points automatically awarded to their opponents. By taking 17 Nëntori out of the title race, Dinamo's path was cleared, while by doing the same to Partizani, the regime tried to convey the idea that there was no unequal treatment. But it wasn’t convincing at all; the regime's dislike of 17 Nëntori was evident.

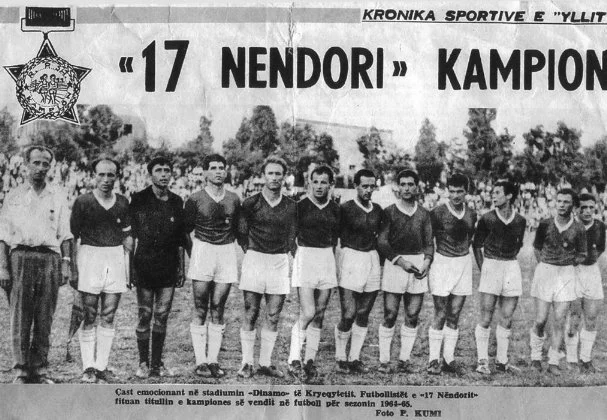

Newspaper article showing the 17 Nëntori squad.

Photo Credit: Kronika SportiveIt was August 1920 when several young people met at the Café Kursal in Tirana and founded the Sport Klub Tirana. This was just six months after the government headed by Sulejman Delvina declared Tirana the capital of Albania, ahead of other more developed cities such as Shkodra or Korça. National institutions would be installed in Tirana, designed to be the new centre of power, with the goal of extending the presence of the state to the rest of a young country whose independence from the Ottoman Empire was recognised in 1913 (after the First Balkan War) and whose foundations were still to be laid.

William of Wied accepted Principality of Albania’s throne in February 1914, but left the country on the eve of World War I, unable to assert his authority and undermined by a failed coup d'état, a peasant revolt and neighbouring countries trying to destroy the country's sovereignty. During the chaos of the war, Albania was swallowed up by Italians, Serbs and Greeks, but once ended, it was able to retain its independence with the support of the United States.

Despite efforts to consolidate Albanian institutions, its constant inter-clan struggles, as well as its economic and social underdevelopment, were too much of a burden for the country, which suffered great political instability throughout the 1920s, with as many as five people parading through the prime minister's office in the second half of 1921 and several attempts to establish authoritarian rule. One of the most prominent figures in Albania's troubled politics was Ahmet Zogú who, aided by Yugoslavia, overthrew the government in 1924, proclaimed the First Republic of Albania and was elected president with dictatorial powers. In 1928 he changed course, proclaimed himself king (Zog I), turned his back on Yugoslavia and placed the country under the protection of Mussolini's Italy.

Due to Albania's structural weakness, Italy began to take charge of the country's development in all areas. For example, the National Entity ‘Albanian Youth’ was founded, which operated with Italian technical assistance, but had to have the approval of King Zog I to undertake any activity. It was this entity, which included the Albanian Sports Federation, that organised the first five Albanian league championships between 1930 and 1934. That year, the Entity was transformed into the Albanian Youth Department of the Ministry of Education, while in 1935 the Federation of Cultural and Sports Associations was created, chaired by the Minister of Education and vice-chaired by the head of the Albanian Youth Department. The Federation, ultimately under state control, decided on all aspects of the sports clubs (even their maintenance staff) and was responsible for organising the league championships of 1936 and 1937.

Of the seven league championships held in the 1930s, SK Tirana won the trophy in six of them. A success for the capital that became a success for the state and Zog I, and vice versa. However, some of these titles were marred by controversial episodes that showed a certain favouritism towards the Tirana club.

In 1930, a match in the capital against Skënderbeu Korça brought numerous protests from the visiting team, who were claimed two penalties and had a goal disallowed. The Federation proposed a play-off in Korça, but the club, believing that this would only reassert the refereeing injustices, did not attend the match. In 1937, SK Tirana lost 1-2 against Vllaznia from Shkodra, their main rivals in the title race, although the match officials asked the referee committee to change the result of the match, claiming that he had been pressured by the Vllaznia players to award the penalty resulting in the winning goal. After many months of internal debate, the Federation finally decided to replay the match, but the Vllaznia players did not attend the match.

Fatmir Frashëri leads KS 17 Nëntori out for the fateful fixture against Partizani at the end of the 1966/67 season.

Photo Credit: memorie.alAfter that year, the league was not resumed until the end of World War II. In the meantime, Italy invaded Albania in April 1939, after years of economic and political intervention in the country. Despite initial support, various communist groups, with the help of Yugoslavia, came together in 1941 to form the Communist Party of Albania, which in 1942, led by Enver Hoxha under the banner of the National Liberation Movement, rebelled first against Italian and then German occupation. After taking control of the country in November 1944, a provisional government was set up under Hoxha, who, after annihilating the exponents of the former monarchy and his political enemies, designed and implemented a brutal communist regime faithful to Stalinist doctrine.

Internationally, Hoxha's regime was characterised by hermeticism and a compulsive isolationism, which prompted him to build and break ties with Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union and China. This affected Albanian football: Hoxha denied the national team participation in numerous European Championship and World Cup qualifiers, because of political reasons and the absence of diplomatic relations with other countries. Furthermore, Albania is the only country to have boycotted no less than four editions of the Olympic Games. On the domestic front, Hoxha undertook an absolute centralisation of power and invaded, through the state, all aspects of the country's socio-cultural life. This included, of course, football. Thus, following the example of the other communist countries, he took advantage of the growing popularity of football to create teams through which the state could also express itself on the pitch.

FK Partizani, named after the Albanian partisans who participated in the liberation of the country, was founded in 1946 based on Ushtria (‘Army’), which was the result of the merger of two military teams that participated in the 1945 league. Although it did not have such a bad reputation among Albanians (after all, the Partisans had fought for the country), it was the favourite team of Politburo members, who were regular attendees in the stand.

But no one took their hobby as seriously as Petrit Dume, Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces since 1956, who would usually head down to the dressing room at half-time and order that underperforming players were replaced. Once, when FK Partizani was returning to Tirana after a defeat, Dume followed the team bus, stopped it and got on to insult the players. Apart from Partizani, KS Dinamo, linked to the Ministry of the Internal Affairs, was also created in 1950. The two teams shared all the league championships between 1947 and 1964, as they were reinforced with players doing their military service and, from time to time, the government ordered the country's best players to join one team or the other.

17 Nëntori v Ajax in the European Cup, 16 September 1970.

Photo Credit: memorie.alIn that football landscape, KF Tirana was the missing piece - a symbolic link to the old monarchic era. The regime tried to sever this connection by renaming it 17 Nëntori, but its fans continued to call it ‘Tirana’ - a clear gesture of opposition to the dictatorship. Moreover, because they continued to produce good talent, 17 Nëntori was a regular victim of the regime's transfer policy: many players were called up for military service and, once they had finished, were forced to stay at either FK Partizani or KS Dinamo. In 1961, Skënder Halili disobeyed the order to remain with KS Dinamo after his military training and was suspended without playing for a year. Later, when he returned to play for 17 Nëntori, he was arrested for alleged smuggling when $60 was discovered at his home under dubious circumstances. This and other similar cases provoked outrage, until in 1963 the regime took the decision that state-owned clubs would no longer retain players who had completed their military service.

Many players returned to their home clubs, and 17 Nëntori became a competitive team again. Thus, in the 1964/65 season, they managed to break the FK Partizani and KS Dinamo duopoly by winning their first league title after World War II with a one-point lead over both teams, while in the 1965/66 season, 17 Nëntori and FK Partizani finished level on points. How were they to break the tie? In the past, the Federation had used the ratio of goals scored to goals conceded, but on this occasion, that rule would result in 17 Nëntori being champions. To deprive them of the title, the Federation opted for a play-off match between 17 Nëntori and FK Partizani. As expected, several members of the Politburo came to the stadium, where they saw 17 Nëntori winning 2-1 and claiming the title. The ecstatic fans chanted not only ‘Tirana up!’, reviving the club's former name, but also ‘Down with the Reds’. Yes, the FK Partizani players wore red shirts, but that message was clearly aimed at the communist leaders present in the stadium.

That was too much for the regime. Convinced that 17 Nëntori could not win the title again in 1966/67, the Politburo devised subtle ways of undermining their potential, such as sending two of their best players, Ali Mema and Gëzim Kasmi, off for military service. Nevertheless, 17 Nëntori led the standings from the start, and went into the derby against FK Partizani on matchday 19 undefeated. And just like the previous year, 17 Nëntori won again - the same result, 2-1, and identical claims against the ‘reds’. 17 Nëntori's audacity had gone too far, so the regime took the expeditious decision to exclude them from the competition along with FK Partizani, in a show of false equidistance. KS Dinamo won their last three league matches, and thus claimed the championship. UEFA, however, did not give credibility to the farce and did not allow them to participate in the following season's European Cup. Nëntori, on the other hand, managed to recover by winning the league in the following two seasons, proving that the resistance to Enver Hoxha's manufactured football was still alive.

17 Nëntori squad, 1980s.

Photo Credit: Balkanic Football