Words by Paul Grech | Published 12.09.2025It shows up without invitation yet always feels like it belongs. Tucked into the shadows of hostel lobbies, wedged between vending machines in office break rooms, glowing beneath the lights of rooftop bars. It waits, not grand or loud, but resolute.

No screen, no login, no instructions. Just a handful of figures, a ball, and the sound of wood or plastic coming alive in bursts of sudden, communal energy.

You’ll find it in Berlin, where techno blares and night stretches into morning. And in a dusty Sicilian bar, where old men nurse coffee and grappa, and teenagers square off with shouts that echo into the street. It’s both local and universal, unbranded but unmistakable.

This is not just a game, but a ritual. An elemental clash of reflex and rivalry, where strangers become teammates, and the line between play and passion disappears.

It’s where office grudges are settled and friendships are made in four-goal bursts. It’s as much a part of modern mythology as the jukebox or the dartboard, passed from generation to generation without ceremony.

You don’t schedule a game; rather, you stumble into one, and suddenly you’re in a battle for the ages. No matter the city or the decade, it’s there, spinning, rattling, reminding you what joy feels like when it’s unscripted and shared. Not an icon by design, but by endurance.

A symbol of connection, chaos, and something very close to magic.

Table football is all of that and, somehow, still more.

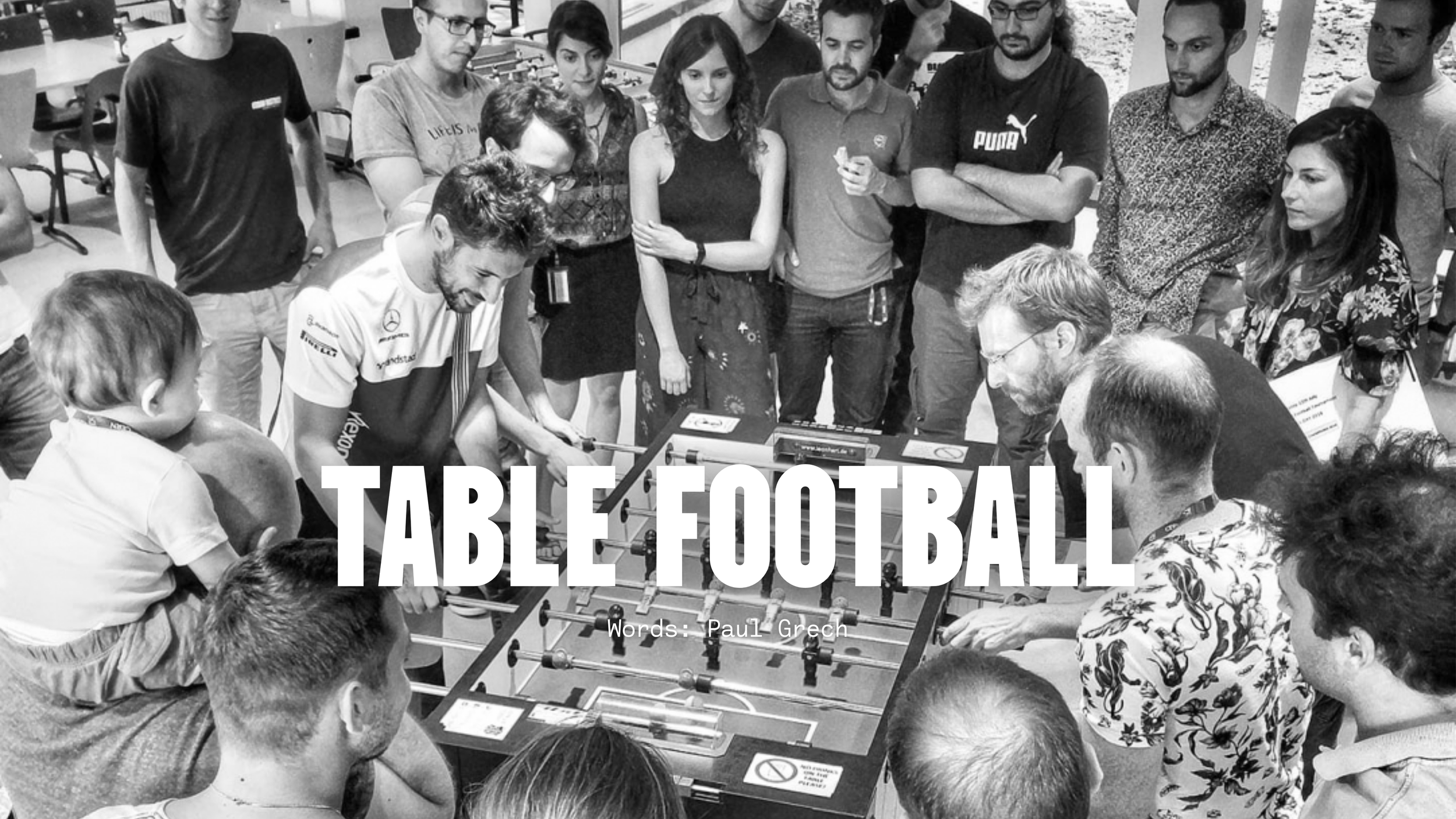

A charity table football tournament takes place every year at CERN, Geneva.

Photo Credit: Parul PantThat, at least, is the name with which the game is known in some parts of the world. In the United States and Canada, for example, it is widely known as foosball, a term derived from the German word Fußball, meaning "football". The term stuck in North America and became the standard despite the game itself having European origins.

In Germany, the game is commonly referred to as Kicker, a name also used in Austria and Switzerland. The French tend to refer to it as baby-foot while in Italy, it's called calcio balilla, and in Spain, futbolín.

These names often reflect both cultural preferences and linguistic quirks, showing how a single game can be deeply integrated into different regional identities.

Despite the variations in name, the essence of the game remains the same: players manipulate rods with attached figures to strike a small ball into the opponent’s goal.

When a game like table football becomes as widespread and familiar as it is today, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking it has always been part of our cultural fabric. Its simplicity and physicality make it feel older than it is, a kind of analogue heirloom that predates screens and consoles, passed down through generations. For most people, it is an echo of their childhoods.

But in truth, table football is a relatively recent invention, with its origins tracing back less than a century. Various prototypes emerged across Europe in the early 20th century. In particular, the game as we know it today owes much to one man in particular: Alejandro Finisterre.

While his story is not widely known, Finisterre lived a truly remarkable life. Born as Alexandre Campos Ramírez in 1919 in Finisterre, a windswept coastal town in Galicia, Spain, he grew up in a region steeped in folklore, resilience, and maritime tradition. From an early age, he displayed a strong intellectual curiosity and a flair for the arts.

His family moved to Madrid during his adolescence, where he came into contact with a vibrant cultural scene and the growing political tensions that would soon erupt into civil war.

As a young man, Finisterre was swept up in the fervour of the Spanish Civil War. He aligned with the Republican cause and found himself on the front lines of one of the most turbulent periods in Spanish history. Deeply affected by the violence and upheaval, he developed a lifelong commitment to anti-fascism and artistic expression.

During the Spanish Civil War, Finisterre remained in Madrid, a stronghold of the Republican forces, which fought to defend Spain’s democratically elected government against the fascist uprising led by General Franco. His commitment to these ideals was not only political but also personal. He risked his life by staying in Madrid.

This presence in the besieged city reflected both his solidarity with the Republican cause and his belief in the power of culture as a form of resistance. Yet it came at a huge cost. The city suffered heavy bombardment during this period and, in one such shelling in 1936, he was severely injured and was hospitalized for a long period.

Despite the chaos and violence surrounding him, Finisterre remained engaged in literary and political circles, contributing to anti-fascist publications and maintaining connections with fellow artists and thinkers.

Like many Republicans, when Madrid fell to Franco’s forces in 1939, Finisterre was forced to flee. Facing the threat of imprisonment or execution under the new regime, he crossed the border into France, joining the wave of Republican exiles escaping retribution.

Initially, like many refugees, he endured difficult conditions in border camps or temporary housing. Despite these challenges, he remained intellectually active and politically committed. He continued to write and engage with anti-fascist circles, maintaining contact with fellow exiled artists, writers, and political activists.

Eventually, not even France felt safe. The political climate shifted with the onset of World War II and later the consolidation of Franco’s dictatorship. France became increasingly precarious for those who had opposed the regime.

Alejandro Finisterre, the founder of table football, in 2006.

Photo Credit: Mercè GamellMore specifically Finisterre, with his history in publishing, had been under threat from Francoist agents even while in exile. The Spanish regime actively pursued prominent Republican exiles abroad, especially those involved in journalism, literature, or political activism. There were credible threats against him, and the risk of extradition or abduction loomed large.

Given the increasing reach of the Franco regime and the growing web of post-war intelligence networks that often collaborated with authoritarian states, Finisterre made the decision to leave Europe altogether. South America offered a more distant and welcoming refuge, a place where he could continue his intellectual work with less immediate danger and in the company of fellow exiles and sympathetic allies.

His first port of call was Ecuador, he immersed himself in the world of literature, founding a poetry magazine in Quito called Ecuador 0° 0' 0" that quickly became a sanctuary for exiled Spanish writers and a platform for avant-garde thought.

By the early 1950s, Finisterre moved to Guatemala, drawn by its energetic cultural life and revolutionary spirit. It was there that he deepened his relationship with León Felipe, a fellow Spanish exile and one of the most poignant poets of the Republican diaspora.

Felipe, with his white beard and thunderous verses, had become a voice for those silenced by Franco’s regime. Finisterre, recognising the power and urgency of Felipe’s words, took it upon himself to preserve and promote his legacy. He published Felipe’s work at a time when it was politically dangerous to do so, ensuring that the poet’s voice continued to echo across continents.

Decades later, in Mexico, Finisterre would organise a public homage to Felipe in Chapultepec Park, installing a bronze bust that still stands as a quiet but powerful act of remembrance.

But Finisterre’s time in Guatemala was abruptly cut short. In 1954, following a US-backed coup, the political climate once again turned hostile. One day, he was abducted by agents of the Franco regime and bundled onto a plane bound for Madrid. But Finisterre, ever resourceful and defiant, acted. Concealing a bar of soap in silver foil, he declared it a bomb mid-flight, announcing himself as a political refugee and demanding asylum. His bluff worked. The plane made an emergency landing in Panama, where he stepped off, free once again.

It was a moment of audacious resistance that seemed ripped from fiction.

Eventually, Finisterre made his way to Mexico City, another haven for Republican exiles. There, he founded Editorial Finisterre, a small but prolific publishing house that produced hundreds of titles, many by writers whose works were banned in Spain. He created a home for voices that would have otherwise been erased.

Mexico also brought him into contact with Frida Kahlo. The two moved in overlapping circles of artists, writers, and political dissidents. Theirs was not merely a friendship. Over the course of several years, they developed an intense, clandestine relationship deeply rooted in shared ideals of art, resistance, and emotional honesty.

Kahlo, already marked by physical pain and emotional betrayals, found in Finisterre a final, vital flame.

In her letters, she called him “my beautiful poet boy” and “my last great love,” entrusting him with intimate objects, poems, and confessions in the final months of her life. She wrote with urgency and vulnerability, thanking him for bringing her back to life, even as she teetered on the edge of death.

For Kahlo, Finisterre was both a sanctuary and a spark - someone who, as she wrote, made her believe in love again when everything else was falling apart.

Alejandro Finisterre in 2007.

Photo Credit: LavanguardiaAll of this is evidence of Alejandro Finisterre’s remarkable life. But where does table football come in?

For that, we have to go back to the bombing during Spanish Civil War which saw Finisterre being severely injured and taken to a hospital in Montserrat to recover. There, he was surrounded by young children, many of whom were also victims of the war caused them to become bedridden or maimed.

Seeing that they could no longer play football outdoors, Finisterre was struck by the idea of creating a version of the game that could be played indoors on a tabletop, and most importantly, by anyone, regardless of physical ability.

Drawing inspiration from table tennis, he sketched out the concept of a miniature football pitch, complete with fixed rods holding rows of players that could be spun and slid to kick a small ball across the surface.

The idea was part recreation, part rehabilitation; a way to restore joy and movement to children whose worlds had been turned upside down by conflict. With help from a Basque carpenter named Francisco Javier Altuna, the first prototype was built. In 1937, Finisterre filed a patent for the invention in Barcelona.

However, that was only the beginning of the story. During his escape over the Pyrenees into France, he lost nearly all of his belongings, including the precious patent papers. By the time he settled in Latin America in exile, the rights had effectively slipped away.

Though variations of the game began to appear across Europe and South America, Finisterre never financially benefited from his invention, although he did finance his publishing by manufacturing and selling the game both when in France and in South America.

Still, he remained proud of the idea and continued to claim authorship of what had become one of the most universally beloved pastimes in the world.

In typical Finisterre fashion, he didn’t dwell on what was lost. For him, table football was always less about commercial gain and more about restoring a small sense of normality to those robbed of it by war.

A table football tournament taking place in Fapim, Italy.

Photo Credit: Fapim MuseumIn his later years, Alejandro Finisterre’s life remained as unconventional as the earlier chapters that had taken him through war, exile, and invention. After decades spent abroad, he returned to Spain in the 1980s following the death of Francisco Franco and the restoration of democracy. Though he had lived much of his life in the margins of history, his return was met with quiet curiosity and a certain reverence from those who remembered or had learned of his creation.

Spain was a different country than the one he had fled, and Finisterre, by then in his seventies, found himself unexpectedly celebrated as a folk hero. He was invited to events, interviewed by journalists, and honoured for having invented something that had become a fixture of Spanish culture.

Schoolchildren played futbolín in bars and youth clubs across the country, often unaware of the man who had created it in a hospital bed during the Spanish Civil War.

Now, the man behind the game was finally being recognized.

Despite the acclaim, Finisterre remained humble and often reflective, even melancholic, about what he had lost. He had never regained the patent for table football and as a result never profited from its widespread adoption.

In the final years of his life, Alejandro Finisterre became a symbol of the forgotten inventors, of those who leave a lasting mark not through wealth or fame, but through simple ideas born of empathy and necessity.

He died in Zamora, Spain, in 2007, aged 87. His passing was noted by national newspapers, not with grand headlines, but with a kind of affectionate recognition. Spain had, at last, made peace with one of its quiet revolutionaries.