Words by Jonee | Published 25.06.2025Football kits are far more than fabric; they are vibrant emblems of identity and dynamic canvases of creativity. From the heavy woollen shirts of the 19th-century to the sleek, aerodynamic jerseys of the modern era, football kits have evolved in lockstep with the sport, mirroring societal transformations, technological breakthroughs, and the global explosion of the beautiful game. The “golden age” of football kits, in my mind, spans multiple decades, defined by designs that became symbols of national pride, club devotion, and street fashion.

Let’s delve into the rich history, artistry, and cultural weight of football kits.

Every football kit tells a story. They weave narratives of triumph, misery and belonging. The Netherlands’ orange kit, born in the 1974 World Cup, embodies the fluidity of Total Football, its vibrant hue igniting “Oranjegekte” across Dutch streets. Nigeria’s 1994 kit, with its bold green and black geometric patterns, announced the Super Eagles’ global arrival, resonating with fans from Lagos to London. Brazil’s yellow shirt, reinvented after the 1950 Maracanazo, radiates the samba flair of Pelé and Ronaldinho. Colombia’s colourful designs, from 1980s diagonals to 2018’s retro stripes, mirror a nation’s vibrancy amid adversity. Nike’s 2000s kits, like Arsenal’s deep red or Brazil’s golden glow, fused cutting-edge performance with cultural cachet, while Adidas and Umbro transformed kits into fashion staples. These designs have become cultural touchpoints for people in the modern day, and we see football kits worn in stadiums, at protests, and in music videos. They crop up everywhere.

The evolution of kits reflects football’s journey. Early designs prioritized function—wool for warmth, colours for distinction—but grew into symbols of identity as clubs and nations codified their legacies. The post-war era saw kits globally prominent, their spread amplified by television. The 1970s introduced commercialization, with brands like Adidas branding the Netherlands’ orange with three stripes. The 1980s embraced bold patterns, as Colombia’s kits dazzled. While the 90s globalized kit culture, with Nigeria’s designs sparking streetwear trends.

Adidas and Umbro, alongside Nike, have been architects of this legacy for decades now. Adidas’s three-stripe motif, from 1970s tracksuits to Y-3 couture, bridges sport and style, while Umbro’s heritage designs, like Liverpool’s 1977 red, evoke terrace pride. Adidas and Umbro’s fan fashion influence, doubled with their embrace of terrace culture, created a legacy that endures on pitches, streets, and beyond.

Marco van Basten models The Netherlands’ 1988 home kit.

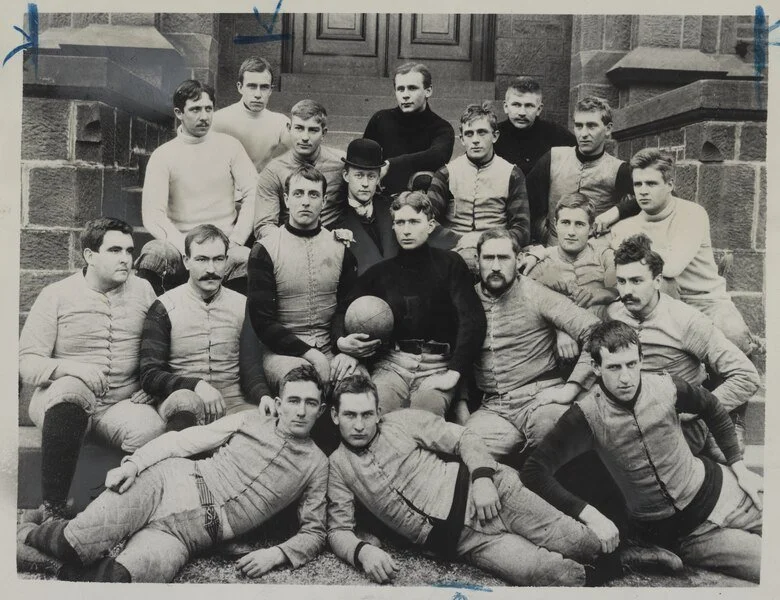

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesFootball’s earliest kits were rudimentary, born from necessity rather than design. In the mid-19th century, when the sport was codified in England, players wore heavy cotton or woollen shirts, often in colours borrowed from school or club affiliations. These early kits were practical but cumbersome. Teams distinguished themselves with simple patterns—stripes, hoops, or halves—since standardized uniforms were rare. The 1870s saw the first international match between England and Scotland, where players donned makeshift kits: England in white, Scotland in navy. These choices laid the groundwork for national identity in kit design.

By the late 19th century, clubs began adopting consistent colours, driven by the growing popularity of the Football League. Arsenal’s red and white, inspired by Nottingham Forest’s donated shirts, and Manchester United’s red (then as Newton Heath’s green and gold) emerged as early examples of kits becoming symbols of local pride. Manufacturers like Umbro, founded in 1924, entered the scene, producing tailored shirts that prioritized function over flair. Umbro’s early designs set a standard for reliability, earning the trust of clubs across England and eventually the world. These kits weren’t yet fashion statements, but they marked the beginning of a visual language that would define football.

The 1920s and 1930s saw incremental improvements. Cotton replaced wool, reducing weight, while designs became more structured, with collars and buttons adding a touch of formality. Clubs like Everton and Tottenham introduced crests embedding local heritage and enhancing the contribution of the football kit to club and supporter identity. International kits also evolved, with England’s white shirts featuring the three lions and Brazil’s early white kits reflecting neutrality. The era’s simplicity laid a foundation for the bold designs that would follow in the post-war era, as kits began to carry the weight of more than just club colours.

The Rutger College football team of 1891, in their rudminetary kits.

Photo Credit: WikiMediaThe post-World War II era saw football kits evolve into powerful symbols of national and cultural identity, as the sport globalized through events like the World Cup. Brazil’s yellow kit, introduced in 1950, became one of the most iconic designs in football history. After the 1950 Maracanazo, where Uruguay stunned Brazil in the World Cup final, a national contest was held to redesign Brazil’s kit, previously white. The winning design, a vibrant canary yellow shirt with green trim, nicknamed “O Canarinho” (The Little Canary), was created by 19-year-old Aldyr Garcia Schlee. The kit debuted in 1958, when a young Pelé led Brazil to their first World Cup title in Sweden. The yellow shirt, paired with blue shorts and white socks, became synonymous with samba football—fluid, joyful, and unstoppable.

The Brazil kit’s brilliance lay in its simplicity. The yellow evoked the sunlit optimism of a nation rebuilding after war, while the green trim reflected the Amazon’s lush vitality. By 1970, when Brazil won their third World Cup in Mexico, the kit was immortalized in colour television. Today, Brazil’s yellow shirt is a cultural icon, worn not just by fans but as a symbol of Brazilian identity, from Carnival to street protests. Its influence extends to fashion, with brands like Nike (Brazil’s kit maker since 1996) producing retro-inspired streetwear that nods to the 1970 design.

Across the Atlantic, Umbro continued to shape kit culture in England. The brand supplied kits for the 1966 World Cup, including England’s red away shirt, worn during their 4-2 final victory over West Germany. Umbro’s designs were understated yet functional, with lightweight cotton replacing wool and subtle details like embroidered crests adding prestige. Umbro’s work with clubs like Manchester United and Everton also fostered a sense of tradition, as fans began wearing replica shirts to matches, a trend that laid the foundation for kits as fan fashion. By the 1960s, Umbro’s influence was global, with the brand outfitting teams in South America and Africa, cementing its role as a pioneer in kit manufacturing.

Adidas, emerging in the 1950s, brought innovation to the scene. Their 1954 World Cup kit for West Germany, a white shirt with black shorts and three stripes, marked their football debut. The use of synthetic blends improved flexibility, while the bold branding set a new standard. Adidas’s early designs, like Hungary’s red and green kits, showed their ability to blend national colors with modern aesthetics, laying the groundwork for their later dominance in kit design and fan fashion.

West Germany, World Cup Winners 1954, wearing an early Adidas kit.

Photo Credit: FIFAThe 1970s marked a pivotal shift for football kits, as commercialization and colour television transformed the sport into a global spectacle. The advent of vibrant broadcasts demanded eye-catching designs. The Netherlands’ orange kit, debuted during the 1974 World Cup in West Germany, stands as one of the era’s defining creations. Designed by Adidas, the kit’s radiant orange—rooted in the national colour of the House of Orange-Nassau—was paired with black trim, black shorts, and the brand’s iconic three stripes along the sleeves. This sleek, minimalist shirt, with its tailored fit and lightweight polyester, contrasted sharply with the bulkier cotton kits of the past.

The 1974 kit was inseparable from Total Football, the revolutionary philosophy pioneered by Rinus Michels and Johan Cruyff. This fluid system captivated audiences, and the orange kit became its visual emblem. Worn during the Netherlands’ run to the World Cup final, the kit shone in matches like the 4-0 thrashing of Argentina, where Cruyff’s artistry dazzled. Despite the 2-1 final loss to West Germany, the orange shirt became a symbol of Dutch creativity and resilience. Cruyff’s personal rebellion—removing one of Adidas’s three sleeve stripes due to his Puma sponsorship, creating a two-stripe version—added another layer of uniqueness, making the kit legendary in football lore.

Adidas’ design, with its prominent trefoil logo and lion crest, introduced branding as a core element of kit identity, setting a precedent for the commercial partnerships we see today. They dominated the 1970s kit market, leveraging innovations like synthetic fabrics and heat-pressed logos to enhance performance and aesthetics. Adidas’ ability to incorporate cultural elements, like flags or heraldic motifs, helped kits transcend the pitch, influencing casual sportswear trends. Their tracksuits, worn by 1970s subcultures like reggae fans and early hip-hop artists, laid the groundwork for kits as fan fashion.

On the other hand, Umbro excelled in club kits, producing designs like Liverpool’s 1977 red shirt, worn during their first European Cup triumph over Borussia Mönchengladbach. The kit’s simple red base, with white trim and an embroidered Liverbird, became a symbol of the club’s golden era. Their reach eventually expanded globally, extending to South America, with kits for Peru’s 1978 team, featuring a red. Umbro’s replicas, increasingly affordable, were worn by fans in pubs and terraces, making football kits more accessible and helping the spread of terrace culture to the streets. By the decade’s end, Umbro’s craftsmanship and Adidas’s innovation had transformed kits into vehicles of identity, setting the stage for the bold designs of the 1980s.

The Adidas Peru kit of 1978.

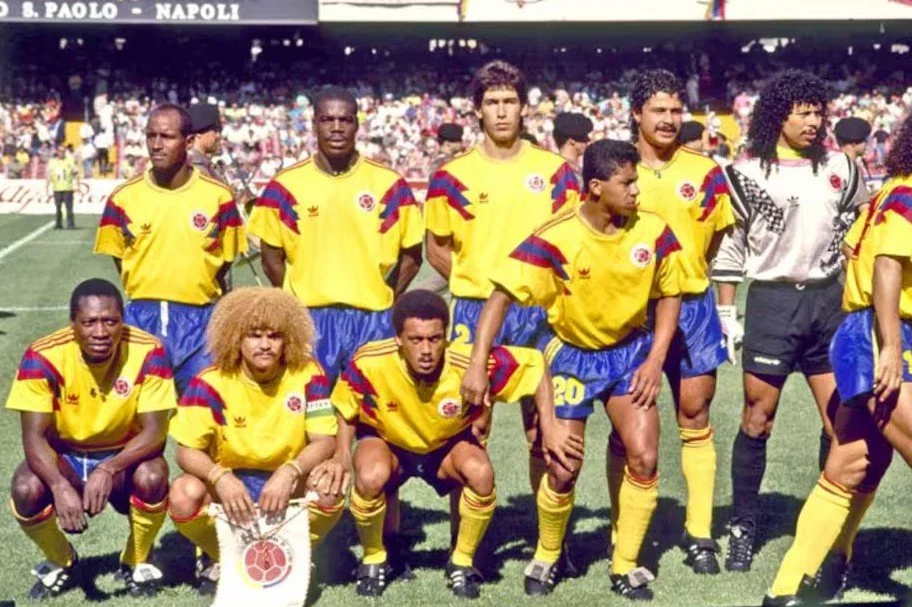

Photo Credit: NASL JerseysThe 1980s were a golden age for football kit design, defined by audacious patterns, vivid colours, and a fearless embrace of experimentation. Kits became visual spectacles, reflecting cultural identities and pushing creative boundaries. Colombia’s national team kits, crafted by Adidas, epitomized this exuberance. The 1986 World Cup qualifying kit, a radiant yellow shirt with bold red and blue diagonal stripes across the chest, captured Colombia’s vibrant spirit. Paired with navy shorts, the design drew inspiration from the nation’s carnival culture, its geometric flair echoing the colourful street art of Bogotá.

Colombia’s 1990 World Cup kit took the vibrancy further, featuring red, yellow, and blue colour blocks that paid homage to the national flag. Worn during Colombia’s first World Cup appearance in 28 years, the kit shone in their 2-0 win over the United Arab Emirates and a dramatic 1-1 draw with West Germany, where Freddy Rincón’s last-gasp goal sparked celebrations. The kit’s bold design resonated deeply with fans during a turbulent decade in Colombia’s history.

Adidas drove kit innovation further. Their 1986 Denmark kit, a halved red-and-white shirt with chevron details, showcased sublimated prints—patterns embedded into the fabric. Adidas’ work with clubs, like Juventus’s 1985 black-and-white stripes with yellow accents, blended sport with art. The brand introduced moisture-wicking polyester, improving player comfort.

Umbro refined its craft with iconic club kits, notably Liverpool’s 1985-86 double-breasted red shirt, featuring pinstripes and a crown logo honouring the club’s European dominance. Worn during their First Division title under Kenny Dalglish, the kit’s embossed Liverbird and tailored fit made it a fan favourite. Umbro’s 1990 World Cup kit for England, with subtle blue diamond patterns, balanced tradition and modernity, its design later inspiring retro streetwear brands.

Umbro’s attention to heritage made their kits timeless, coveted by fans who saw them as extensions of identity. Their work with smaller clubs, like Lens’s 1980s gold-and-red kits in France, preserved a grassroots charm, while global contracts, such as Scotland’s 1986 navy kit with white accents, showcased versatility. Umbro’s replicas, increasingly affordable, flooded terraces and pubs, bridging sport and culture. By the late 1980s, kits were no longer confined to the pitch; they were fashion statements, worn with jeans and Doc Martens, influencing 1980s youth movements from casuals to ravers.

The 1980s kit boom reflected football’s growing commercialization, with brands leveraging World Cups and European competitions to reach new markets. They set a high bar for the 1990s.

The Colombia squad at Italia ‘90.

Photo Credit: El EspectadorThe 1990s were a transformative decade for football kits. Nigeria’s national team kits, crafted by Nike, became immensely popular, redefining kit design with their bold aesthetics and cultural resonance. The 1994 World Cup kit, a vibrant green shirt adorned with black and white geometric patterns inspired by Yoruba and Igbo textiles, was a radical departure from the era’s more conventional designs. Worn by stars like Jay-Jay Okocha, Rashidi Yekini, and Sunday Oliseh, the kit earned the Super Eagles a cult following. The loose fit, typical of 1990s kits, and its intricate patterns made it a visual standout.

Nike’s work with Nigeria showcased their knack for fusing cultural heritage with modern aesthetics. The 1994 kit’s design drew from traditional Nigerian art, with angular patterns evoking woven fabrics, making it a wearable symbol of national pride. Its global appeal was immediate, with replicas selling out across Europe and North America. The 1996 Olympics kit, building on this legacy, featured a deeper green with intricate eagle motif. Worn during Nigeria’s gold-medal run, including a 3-2 upset over Brazil, the kit cemented the Super Eagles’ reputation for iconic designs. These kits influenced global fashion, with urban brands like Fubu and Sean John adopting similar bold prints and sporty silhouettes. The 2018 World Cup kit, a Nike revival with a zigzag green-and-white pattern, paid homage to 1994, selling three million units pre-release and becoming a streetwear staple worn by celebrities like Wizkid and Skepta.

Brazil’s 1998 World Cup kit, also by Nike, reinforced the yellow shirt’s status as football’s most iconic and recognisable design. Building on the legacy of the 1958 “O Canarinho,” the 1998 kit featured a modernized fit with subtle blue star accents above the crest, representing Brazil’s four World Cup titles, and a sleek collar for a polished look. The kit became a global bestseller. The kits basically sold themselves. Nike’s marketing, with campaigns featuring Ronaldo’s step overs and Rivaldo’s flair, amplified the kit’s reach. The kit’s influence extended to fashion, with Nike producing retro-inspired streetwear lines in the 2000s.

Nike’s designs for Nigeria and Brazil highlighted their 1990s ascendancy. Their global marketing machine, fuelled by stars like Okocha and Ronaldo, turned kits into commodities, worn by fans and non-fans alike. The 1994 Nigeria kit’s streetwear appeal, with its oversized fit, inspired hip-hop artists, while Brazil’s 1998 kit became a favourite item to be worn outside of the stadium.

Adidas, also produced iconic kits like Germany’s 1990 World Cup shirt, with its black, red, and yellow chest pattern evoking the reunified nation’s pride. Worn during their 1-0 final win over Argentina, the kit’s bold design and ClimaCool technology set a standard. Adidas’s 1998 Real Madrid kit, with purple accents, worn during their Champions League triumph, blended elegance with innovation. The brand’s three-stripe motif became a cultural shorthand, influencing hip-hop and rave subcultures, with logoed tracksuits worn by artists like Run-DMC. Adidas’s kits, from Germany’s tricolour to Jamaica’s 1998 green-and-yellow debut, showcased their ability to merge national identity with global appeal, laying the groundwork for fan fashion’s crossover.

Umbro, rooted in heritage, produced nostalgic 1990s kits like England’s 1996 Euro shirt, with indigo details evoking 1966. Worn during the “Football’s Coming Home” era, the kit resonated with fans, its replicas flooding Wembley. Umbro’s Manchester United 1999 Champions League kit, a red-and-black design worn during their dramatic 2-1 comeback against Bayern Munich, reinforced their legacy. Umbro’s focus on classic cuts and embroidered crests appealed to purists amid football’s commercialization, with replicas becoming everyday fashion, worn with jeans and trainers. Their work with smaller clubs, like Lazio’s 1990s sky-blue kits, preserved a grassroots charm, bridging sport and culture in a globalized world. The 1990s, with Nigeria’s bold prints and Brazil’s golden glow, marked a peak in kit culture, setting the stage for the 2000s’ design revolution.

The 1990s proved to be a significant era for kit design; not just for the iconic kits produced throughout, but for how kit design was somewhat reigned in as we entered the new millenium.

Nigeria at the 1996 Olmpics.

Photo Credit: These Football TimesThe 2000s marked a golden age for Nike’s football kits, as the brand redefined the meaning of football kits with daring designs and cutting-edge technology. Nike’s 2002 World Cup kits showcased their ambition to fine-tune what was already a successful template for kits, but in many ways, their quest for perfection led to some design choices being sacrificed in favour of simplicity. Still, it doesn’t make them any less iconic.

Brazil’s yellow kit featured subtle green piping and a modernized fit, worn during their fifth World Cup triumph in Japan and South Korea, while Nigeria’s fresh design continued the Super Eagles’ tradition of vibrant expressionism while tapping into shared heritage. The green shirt, with a gradient fade and eagle-inspired chest pattern, evoked the 1994 classic while introducing Nike’s Dri-FIT technology for breathability. Its oversized fit aligned with 2000s streetwear trends, which have come back in fashion today. The design’s cultural roots, drawing from Nigerian textiles, made it a favourite among Nigerian people both home and abroad. The Netherlands’ 2006 World Cup kit, a modernized orange shirt with black accents, paid homage to the 1974 Total Football era. Worn during their 2-1 win over Ivory Coast, the kit’s sleek silhouette and lion crest embodied Dutch pride. These kits became driver during international tournaments, empowering people and contributing to the cultural celebration of football across the globe.

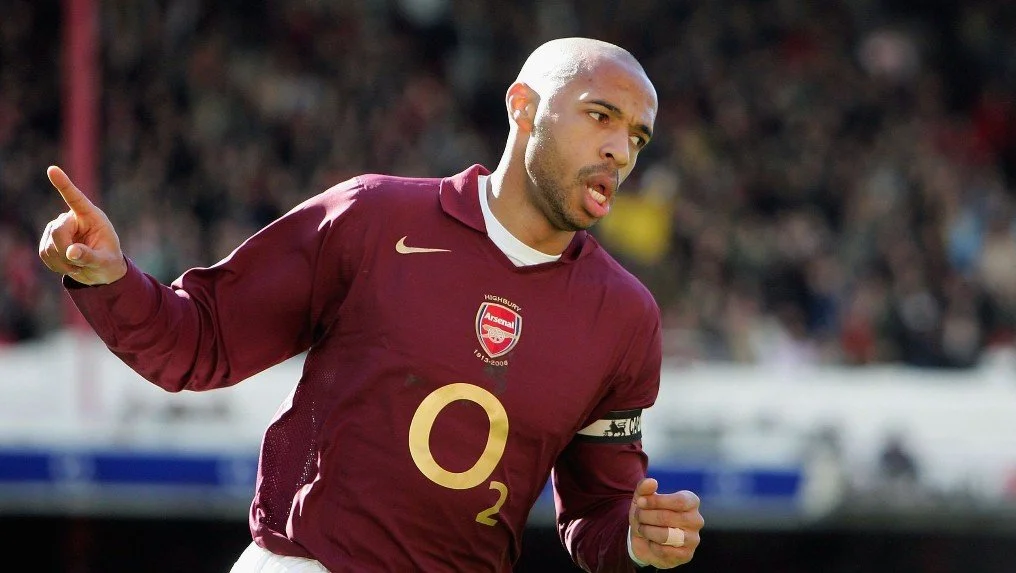

Nike’s 2000s club kits were equally transformative and still have mass appeal today. Arsenal’s 2005-06 “currant red” kit, marking their final season at Highbury, featured gold trim and a retro crest, blending nostalgia with modernity. Worn by Thierry Henry during Arsenal’s unbeaten Premier League run, the kit became a fan favourite. Manchester United’s 2008 Champions League kit, a red-and-white halved design, was worn during their 2-1 final win over Chelsea in Moscow. While performability was prioritised, the aesthetic appeal of these kits turned them into fashion statements.

Reebok contributed a rare entry in Colombia’s 2001 Copa América kit. The yellow shirt, with red and blue geometric patterns inspired by the national flag, celebrated Colombia’s first Copa title, hosted on home soil. Led by Iván Córdoba, Colombia’s 1-0 final win over Mexico sparked nationwide euphoria, with fans donning replicas in Bogotá’s plazas. Reebok’s brief foray into football kits demonstrated how smaller brands could challenge Nike and Adidas by embracing daring aesthetics, though their limited market share kept them niche.

Adidas’s influence on fan fashion likewise great further, through collaborations with designers like Yohji Yamamoto, whose Y-3 line fused sportswear with haute couture. Their three-stripe tracksuits, worn by hip-hop artists like Jay-Z, became 2000s fashion staples, bridging football and urban culture. The produced classics like France’s 2006 World Cup kit, a blue shirt with a red stripe, worn during Zinedine Zidane’s iconic head-butt in the final. Adidas’s Bayern Munich 2001 Champions League kit, with silver accents, and Argentina’s 2006 sky-blue and white stripes, worn during Lionel Messi’s World Cup debut, likewise blended heritage with modernity.

Umbro continued to be a presence within the kit scene, though less dominantly, and began work with smaller clubs. They produced Lens’s 2000s red-and-yellow kits and Santos’s white offers. Though less dominant, they produced nostalgic gems like England’s 2009 kit, a tailored white shirt with red trim evoking memories from 1966. Worn during their 5-1 qualifier win over Croatia, the kit appealed to purists, its classic cut contrasting Nike’s flashiness.

We didn’t know at this stage that foundations had been put in place for the football kit scene to boom, and in the decade that followed, kits took on a completely different meaning.

Thierry Henry in Arsenal’s famous 2005-06 jersey.

Photo Credit: Vocal MediaThe 2010s marked a transformative era for football kits. Fuelled by social media, the boom in retro streetwear style and the need for clubs to push the boat out, football kits became a mixture of jersey, fashion and culture.

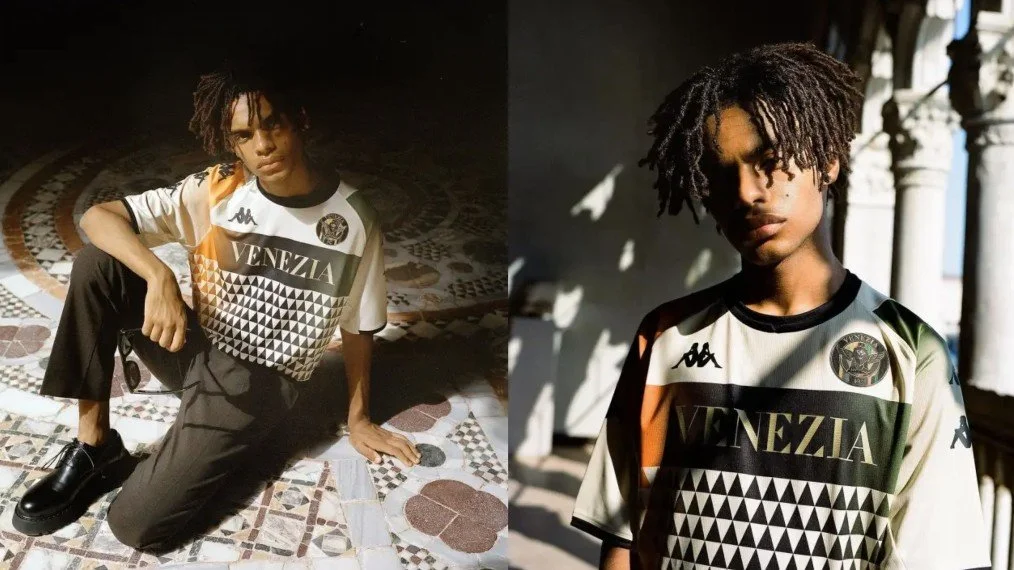

While national kits like Nigeria’s 2018 Nike design with its green-and-white zigzag pattern, the Netherlands’ 2014 minimalist orange, Brazil’s 2018 textured yellow, and Colombia’s 2018 tricolour stripes captured attention, the decade’s true revolution came from clubs redefining kit fashion. Teams like Venezia, Paris Saint-Germain, Juventus, Ajax, Roma, and Arsenal really raised the bar, crafting jerseys that transcended football to become items which blended art, culture, and commerce in unprecedented ways.

Venezia FC, emerged as football’s style icon, dubbed the sport’s most fashion-forward club. Their 2021-22 Kappa kits, designed with New York’s Fly Nowhere studio, featured mosaic-inspired patterns and gold accents evoking Venice’s Ca’ d’Oro palace. The home kit, blending black, green, and orange, sold out instantly, with fans praising its artistic elegance over traditional football aesthetics.

Venezia’s 2024-25 Nike Nocta kits, backed by Drake’s sub-brand, introduced blue-and-gold designs supporting local environmental initiatives, their sleek look books resembling Vogue spreads. Unlike mass-market national kits, Venezia’s jerseys targeted fashion elites, appearing in Milan’s boutiques and influencing designers with their architectural motifs, from tailored jackets to avant-garde accessories.

Paris Saint-Germain’s 2018 Jordan collaboration redefined kit culture, merging football with streetwear’s prime. The black-and-white third kit, featuring the Jumpman logo, was a historic crossover, worn by Neymar and Kylian Mbappé during PSG’s Ligue 1 dominance. Its sleek design, with red accents nodding to Jordan’s Chicago Bulls, became a fashion staple, styled at Paris Fashion Week and urban festivals. The 2020-21 Jordan fourth kit, a gradient purple with gold logos, further blurred sport and style, its hype driven by Instagram campaigns featuring PSG’s global stars. Fans embraced the kits as symbols of status, pairing them with Air Jordans, cementing PSG’s role as a fashion juggernaut beyond football’s traditional fan base.

Juventus, under Adidas’s stewardship, pushed boundaries with their 2019-20 third kit, a collaboration with London’s Palace skate brand. The fluorescent green shirt, with optical-illusion graphics and neon logos, fused Turin’s calcio heritage with street culture, worn during Juventus’s Serie A title run. Its bold aesthetic landed on fashion runways, inspiring designers like Virgil Abloh to incorporate similar high-vis elements. Juventus’s 2021-22 fourth kit, with geometric patterns inspired by Turin’s nightlife, continued this trend, its pink-and-blue palette a social media darling. These kits elevated Juventus beyond club loyalty, appealing to global trendsetters who saw them as wearable art.

Ajax’s 2021-22 third kit, by Adidas, paid homage to Bob Marley’s “Three Little Birds,” a fan anthem. The black base, with red, yellow, and green reggae-inspired accents, sold out rapidly, worn during Ajax’s Eredivisie campaign. Its cultural resonance, blending Amsterdam’s music scene with football, made it a festival favourite, styled with bucket hats and vintage denim. Roma’s 2021-22 New Balance kits, with their deep red and mustard yellow evoking 1980s retro, drew inspiration from the Eternal City’s architecture. The home kit, worn during Roma’s Europa Conference League triumph, featured a subtle Colosseum motif, resonating with fans and fashionistas alike. Arsenal’s 2022-23 Adidas third kit, a pastel pink with navy accents, nodded to London’s diversity, its clean design a streetwear hit, worn by Bukayo Saka and styled at urban events.

These clubs, unlike national teams with broader appeal, crafted kits ways to boost engagement, visibility and revenue. Venezia are the best example of this. Their artisanal approach contrasted with PSG’s hype-driven model, while Juventus and Ajax leaned on subcultural collaborations. Roma and Arsenal tapped into local heritage, creating jerseys that doubled as cultural touchpoints for supporters. Their success was driven by social media, where fans shared unboxings, styling videos, and custom designs on platforms like Instagram and TikTok.

Limited-edition releases, like Venezia’s numbered kits or PSG’s Jordan drops, sparked frenzy, with resellers demanding almost double the price for some. Streetwear brands like Supreme, Off-White, and Patta collaborated with kit makers, producing hybrid jerseys that merged football crests with graphic logos, while fans customized kits with retro name sets or ironic prints, turning them into personalized artefacts.

Adidas, Kappa and Umbra have played pivotal roles in this era. The trefoil logo and luxury-inspired accents have hit runways, blending terrace culture with high fashion. Collaborations with Stella McCartney and Palace elevated Adidas’s three-stripe aesthetic, appearing on bomber jackets and sneakers, reinforcing their fan fashion dominance. Umbro, revitalized, crafted heritage-driven kits like Peru’s 2018 white-and-red sash and Chapecoense’s green design. Umbro’s subtle approach appealed to purists.

Because of this, the 2010s saw football kits take on new meaning as they transcended sportswear and became incrddibly fashionable, with many leaving behind their working-class roots on the terraces.

One of many popular and stylish designs released by Venezia.

Photo Credit: Sole SupplierFootball kits have transcended their origins as sportswear, becoming integral parts of fan fashion and cultural expression. Adidas and Umbro, two of football’s most successful brands, have been architects of this transformation, crafting kits that embody identity, innovation, and style. Their influence stretches across decades, from the Netherlands’ blazing orange to Nigeria’s bold patterns, Brazil’s radiant yellow, and Colombia’s colourful exuberance, shaping a global culture where kits are as much about fashion as fandom.

While Nike’s rise in the 2000s pushed boundaries, Adidas and Umbro’s legacy of blending heritage with modernity cemented their role as fan fashion pioneers, creating a sartorial language that resonates worldwide.

It can’t be understated how much Adidas’s crossover into terrace fashion exploded through subcultures—hip-hop artists like Run-DMC rocked three-stripe tracksuits in the 1980s, while 1990s ravers paired Adidas kits with baggy jeans. Their three-stripe motif is a cultural juggernaut, instantly recognizable from the 1970s West Germany kit to today’s cutting-edge designs. The brand’s early work, like the 1974 Netherlands orange kit, introduced branding as a design cornerstone, with stripes adorning sleeves and tracksuits. By the 1980s, Adidas’s kits for Colombia, with their tricolour diagonals, embedded national pride, while the 1990 Germany shirt’s black-red-yellow pattern became a reunification emblem.

The 2000s saw Adidas elevate kits to high fashion with Y-3, Yohji Yamamoto’s collaboration blending Juventus’s 2010s designs with couture silhouettes. Kits like Real Madrid’s 2014 dragon-inspired third shirt, worn during their Champions League triumph, doubled as runway pieces, influencing designers like Balenciaga to adopt sporty aesthetics.

Adidas, Umbro and Nike have all understood the value of kits as storytelling tools, weaving club and national histories into fabric. This is, ultimately, what makes them successful, and provides the driver for football kit to be truly representative of fan and club identity.

Today, Adidas’s three-stripe logo is a fashion shorthand, adorning sneakers, bomber jackets, and customized kits, uniting fans and trendsetters in a shared aesthetic.

Umbro, rooted in English football’s heart, crafted kits that evoke nostalgia and authenticity, resonating with purists and fashion enthusiasts alike. Their 1966 England red kit, worn during the World Cup final’s 4-2 victory, remains a cultural touchstone, its embroidered three lions a symbol of national pride. Umbro’s 1977 Liverpool kit, a simple red with white trim, worn during their first European Cup win, became a terrace icon, its replicas flooding Anfield. The brand’s tailored cuts and embossed crests, seen in Everton’s 1980s blue kits, contrasted with flashier trends, fostering a grassroots ethos.

Umbro’s global reach included Brazil’s 1970 yellow kit, a nod to their versatility, and Peru’s 1978 red-sashed design, evoking Andean heritage. In the 1990s, Umbro’s England Euro 96 shirt, with indigo accents, captured the “Football’s Coming Home” zeitgeist, its retro replicas surging in vintage shops today. The 2000s saw Umbro craft understated gems like England’s 2009 white kit, worn during a 5-1 rout of Croatia, appealing to fans craving tradition amid commercialization. Umbro’s work with smaller clubs, like Santos’s 2010s white kits honouring Pelé, preserved football’s romantic soul, their jerseys styled at music festivals with retro trainers and bucket hats, blending sport with bohemian flair.

Adidas’s Nigeria 1980s kits, with green-and-white patterns, and Umbro’s Manchester United 1999 red-black Champions League design, worn during their dramatic 2-1 comeback, became cultural artefacts, their replicas cherished by collectors.

The 2010s amplified this legacy, with Adidas’s Juventus 2019 Palace collaboration and Umbro’s Peru 2018 sash kit sparking social media frenzies. Fans shared styling tips on Instagram, pairing Adidas’s Germany 2014 kit with high-top sneakers or Umbro’s Lens 2000s designs with distressed denim, creating hybrid looks. Streetwear giants like Supreme and Off-White drew inspiration, producing football-inspired tees, while fans customized kits with retro name sets—Cruyff, Valderrama, or Okocha—turning jerseys into personal canvases.

Adidas and Umbro’s influence endures in a world where kits are dual-purpose: performance-driven and culturally resonant. Technologies like Adidas’s PrimeKnit and Umbro’s lightweight weaves prioritize athlete comfort, while sustainable materials reflect modern values. Their designs, from Adidas’s Y-3 elegance to Umbro’s nostalgic simplicity, bridge generations, worn by fans chanting in stadiums, rapping on stages, or strutting at fashion weeks.

As football’s golden age of kits continues, Adidas remains its beating heart, crafting a legacy where the beautiful game’s style unites the world, from pitches to runways, in a vibrant tapestry of identity and pride.

Football kits have carved a unique space in our lives, threading together the fervour of fan hood with the freedom of personal taste, transcending the boundaries of club allegiance to become vibrant expressions of who we are. No longer confined to the colours of the team we inherit from family or hometown, kits have evolved into a canvas where passion for the beautiful game meets individual style. They are worn not just to chant from the terraces but to declare our aesthetic, our mood, our identity.

The act of choosing a kit, with its bold hues or subtle patterns, reflects a love for football’s drama and a desire to stand out, blending the collective roar of the stadium with the quiet confidence of personal flair, but it also solidifies a decision in nailing your colours to the mast. From teenagers pairing retro designs with sneakers to artists reimagining jerseys as protest art, kits have become a universal language, unbound by geography or loyalty. They carry memories—of late-night matches and shared triumphs—yet also invite reinvention, as fans mix and match colours that spark joy, from vibrant oranges to deep reds, regardless of club crest.

This duality makes kits enduring: they anchor us to football’s tribal roots while liberating us to craft our own narrative. In a world of fleeting trends, football kits remain timeless, their fabric stitched with stories of devotion and defiance, worn by those who see football not just as a game but as a way to live boldly. As the beautiful game evolves, so will its kits, forever a mirror of our passions and a palette for our individuality, uniting us in a shared love that transcends the pitch and paints our lives with colour.