Words by Jonee | Published 04.06.2025The story of Goodison Park begins with a split. In the late 19th century, Everton Football Club played its matches at Anfield. But disputes over rent and ownership between the club and the landlord, John Houlding, led to a dramatic schism in 1892. While Houlding would go on to form a new club — Liverpool FC — Everton’s directors made a bold decision: to build a new, independent home. That home would be Goodison Park.

This was no ordinary move. At a time when football was still growing from its amateur roots into a national obsession, most clubs shared grounds or played in rudimentary facilities. Goodison Park, by contrast, was designed with ambition and permanence in mind. It became the first purpose-built football stadium in England, and was a serious statement of intent from Everton and their owners.

Situated in the Walton area of Liverpool, nestled tightly within residential streets, the stadium was a marvel for its era. Designed by architect Henry Hartley, it featured grandstands, terracing, and — unusually for the time — separate seating for directors and officials. The site had previously been a nursery garden, and Everton paid £8,000 (a significant sum at the time) to construct the ground. Its opening in August 1892, which involved a friendly against Bolton Wanderers, heralded a new era for football in England.

Goodison was continually evolving. In 1895, it became the first football stadium to have a double-decker stand. By the early 20th century, electric lighting, press boxes, and dedicated changing rooms were added — all innovative for the time. The ground ultimately became not just a place which hosted football matches, but an arena which enhanced the experience of football as spectacle.

As a side note, Goodison also solidified independence for the Toffees. While many clubs were tenants in shared grounds, Everton owned their home. That autonomy gave the club stability and status — something reflected in their early success and stature within the Football League.

By the time the 20th century was underway, Goodison was already more than a stadium. It was a beacon of innovation and a pillar of the professional game. It had become, quite literally, the model others looked to as they built their own homes. The Grand Old Lady had arrived.

The FA quickly recognized and acknowledged Goodison’s stature. It hosted FA Cup semi-finals, England international fixtures, and even British Home Championship matches, underlining its standing as one of the country’s premier venues.

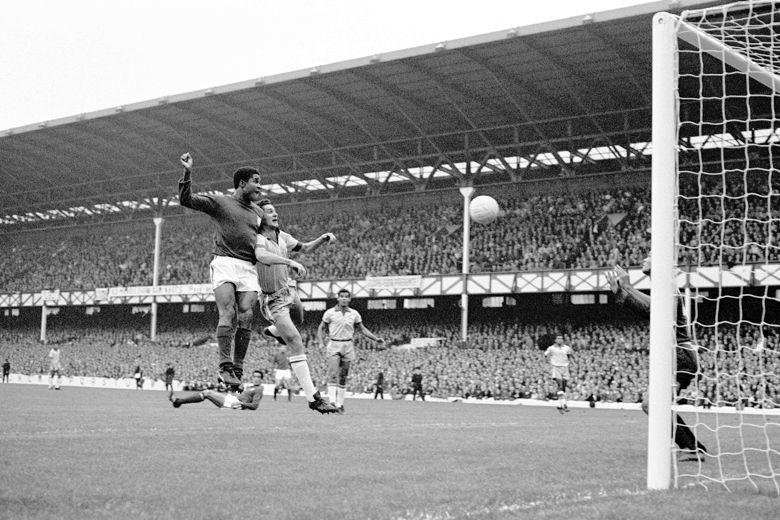

Perhaps its most globally significant role came during the 1966 FIFA World Cup. While Wembley grabbed the headlines, it was Goodison Park that arguably saw the tournament’s most dramatic football. The stadium hosted five matches, including a quarter-final clash between Portugal and North Korea — widely considered one of the greatest World Cup games ever played. Eusebio’s four-goal performance, dragging Portugal from 3-0 down to a 5-3 win, has become the stuff of legend.

The mighty Eusebio plying his trade at Goodison Park.

Photo Credit: The TimesLong before the rise of modern “super stadiums,” Goodison was already setting the standard. It was the first English ground to install under-soil heating, and the first to have a dedicated players’ tunnel. In 1931, it became the first stadium in Britain to have a cantilever stand, allowing for unobstructed views — an innovation later adopted widely across the country. These advancements helped turn football from a rudimentary spectator sport into a more immersive experience.

Goodison was also one of the earliest adopters of floodlights, illuminating night matches long before it became the norm. The Bullens Road Stand, designed by renowned stadium architect Archibald Leitch, remains one of the most iconic structures in football — its crisscross latticework and exposed steel a defining feature of old-school British football design and a hallmark of Leitch’s work

But it wasn’t just the architecture or innovation that gave Goodison its power — it was the atmosphere. The proximity of the stands to the pitch, the steep angles, and the tightly packed rows of seats created a cauldron of noise and intensity. It was, and still is, one of the most intimidating places for visiting teams to play.

Managers and players have long acknowledged Goodison's unique feel. Sir Alex Ferguson once described it as one of the toughest away grounds in the country, not just because of the team, but because of the environment. The roar of the Gwladys Street End, the groans of frustration, the cheers of hope — they all created a living, breathing pressure that few grounds could replicate.

In many ways, Goodison's contribution to English football mirrors Everton's own — steady, foundational, often underappreciated, but deeply influential. While clubs like Manchester United and Liverpool have often dominated the spotlight, Everton and their home ground have provided the league with continuity and character.

While Goodison Park’s architectural innovations and historic matches are integral to its legacy, its soul has always come from the people who fill its stands. Goodison has a deep connection to the community around it, and this intangible culture makes it more special than an ordinary football stadium.

Words: Everton’s supporters play a huge role in the culture which surrounds Goodison Park.

Photo Credit: Liverpool EchoFrom its inception, Everton was a club of the people. Everton’s identity has always been tied to the communities around it and the supporters who lived in the tightly-packed houses where Goodison can be found. Goodison Park was built not in isolation on the city’s fringes, but right in the middle of terraced streets, among rows of red-brick homes, pubs, corner shops, and churches. Even today, a glance around Goodison reveals houses backing up to the perimeter walls, St. Luke’s Church nestled into one corner of the stadium, and generations of fans walking to the ground from the same streets their families have lived on for decades.

This proximity — literal and emotional — has always mattered. Goodison wasn’t just in the neighbourhood; it was part of it. It was the meeting place, the focal point, the stage where families gathered every other Saturday. Fathers, mothers, sons, daughters — all part of the same ritual. It wasn’t unusual for entire families, even generations, to sit together in the stands. This is what creates identities, communities and place.

In a time when football has increasingly become a TV product, Goodison has remained one of the last bastions of a traditional match day experience — unfiltered, unpolished, and authentic. To visit Goodison Park is to visit something akin to a museum, a cultural hotspot of football memory and remembrance.

Goodison Park has witnessed nine league titles, five FA Cups, and a litany of European adventures. From dominance under manager Theo Kelly to the glory days under Howard Kendall, Goodison has been the stage of champions throughout numerous decades.

In the mid-1980s, Kendall’s Everton side were arguably the finest in the club’s history. The team played electric football and dominated domestically. In the 1984–85 season, Everton won the First Division, the European Cup Winners’ Cup, and the Charity Shield, while only narrowly missing out on a historic treble.

Goodison’s European nights during this era were legendary. The most iconic came in the semi-final of the Cup Winners’ Cup in April 1985, when Everton beat Bayern Munich 3–1. The atmosphere was electric — the sound, the passion, the intensity unmatched. Howard Kendall later said, “It was the greatest night I ever had in football,” and many fans still rank it as Goodison’s greatest evening.

Football stadiums are often measured in square metres and seating capacity, but their true significance lies elsewhere — in the rituals, the myths, the emotions they conjure. Every inch of Goodison carries tradition. Fans sit in the same seats their fathers did. Scarves are tied the same way. St. Luke’s Church, a unique building in it’s own right, has become a meeting place for fans pre-match, or in some cases a place for memorial services to take place. It’s part of Goodison’s story and legacy.

Goodison under the lights, radiating it’s magic aura.

Photo Credit: MetroGoodison is a keeper of memories. It holds within its walls decades of first games, family traditions, heartbreaks, and elations. Supporters speak about the stadium in personal, almost spiritual terms. Many have had ashes of loved ones scattered beneath the pitch, a final resting place chosen out of a belief that no place meant more.

The conversation about leaving Goodison is not new. For over two decades, Everton have explored relocation — with earlier proposals in the 1990s and 2000s failing to materialize. The reasons have always been practical: modern football demands modern facilities. Goodison, despite its charm, lacks the infrastructure required for a club with Premier League ambitions and global appeal.

Restricted space, aging facilities, and the inability to significantly expand seating capacity have made it increasingly difficult for the club to compete financially. Match day revenue lags behind rivals, and modern hospitality demands cannot be met within Goodison’s tightly packed footprint. As much as the stadium is loved, the economics of football have made its limitations impossible to ignore.

In 2017, the club announced its intention to build a new stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock, part of Liverpool’s former UNESCO-listed northern waterfront. After years of consultation, design revisions, and planning hurdles, construction began in 2021. The new stadium will meet Everton’s modern needs, and the Toffees will take to the field there for the first time in the coming season.

And yet, for all the excitement, the move brings an inevitable sense of grief. The final season at Goodison has taken on a more emotionally charged atmosphere. Each match has felt heavier, more meaningful. Fans lingered longer after full time. They didn’t want to let go.

For many fans, the new stadium will have to earn its status. Atmosphere can’t be manufactured. Tradition takes time. It will take years — perhaps generations — to replicate the emotional architecture that Goodison holds.

The scenes around Goodison Park on Everton Men’s last match there.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesWhen the final whistle blew on the final game at Goodison Park for Everton Men’s team, there were tears. But Everton fans can take comfort in the fact that Goodison will not be demolished; instead, Everton Women will become the new custodians of the Grand Old Lady, breathing new life into Goodison and heralding the arrival of a new culture of football.

For many though, this is still goodbye.

I’m not an Everton Football Club fan, nor do I have any special connection to the club itself, but I do feel a certain attachment to Goodison Park. It was the first stadium where I attended a game after moving to the UK, and it left an everlasting impression on me. Maybe it’s the beautiful blue, or the walk through the crowd of supporters on the way to the stadium — maybe even the feeling that football history surrounds the place. Whatever it is, it left a mark on me.

I was lucky enough to say my goodbyes during its last Premier League game, which means a lot to me.

I may not be an Everton FC supporter, but I will always be a Goodison Park fan. You’ve done well, our Grand Old Lady.