Words by Andrew Newton | Published 31.01.2026Thomas Marie Madawaska Hemy is a notable gentleman of the Victorian era, and not just for his slightly outlandish name. Slightly outlandish names were very popular amongst the Victorians; just look at Joseph Rudyard Kipling (named after a lake), Egerton Castle (that’s a person, not a place), and Euthanasia Sherman Meade (not a particularly reassuring name for a physician).

In Thomas’ case, the ‘Marie’ part pertains to the Hemy family’s Catholic faith. The ‘Madawaska’ part is in honour of his birthplace.

Which was a ship.

Thomas was born onboard the Madawaska, off the coast of Brazil, during a voyage to Australia in 1852. The ship, which was registered in Canada, was named after the river in Ontario.

Although they had intended to emigrate, the Hemy family appear to have returned from Australia quite quickly and settled back in Newcastle, where Thomas’ father worked as a music teacher. At the age of 14, Thomas went away to sea, and later recounted this period of his life in his book Deep Sea Days, published in 1926. He served in both the British Merchant Navy and the United States Navy and seems to have had plenty of adventures at sea.

An 1894 article about him in The Boys Own Paper, states that Hemy ‘sailed both Pacifics, both Atlantics, and the Indian Sea [and] has seen murder and mutiny aboard ship’. The same article indicates that he had endured ‘terrible things’ at the hands of the press gangs in South America and that he’d been involved in several shipwrecks. At one point, the ship that Hemy was serving on was becalmed off Cape Horn for two months and, due to a lack of provisions, the crew almost starved to death.

What Thomas was truly notable for was art; he was a painter. When he finished his naval career and returned to land, in 1873, he studied at the Newcastle School of Art and in Antwerp. His nautical experiences appear to have influenced the choice of subjects for his paintings, as he became known for maritime scenes, particularly those of shipwrecks. Amongst his best known works are The Wreck of the ‘Birkenhead’ and The Burning of the ‘Kent’ East Indiaman. Thomas Hemy’s work was regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy and at provincial galleries throughout the country.

The Hemy family appears to have been a particularly artistic one, at least three of Thomas’ twelve siblings also became artists. The eldest of the four artists, Charles Napier Hemy, is the best known and, like Thomas, was known for maritime scenes but another older brother, Bernard Benedict Hemy, and a younger brother, Oswin Bede (a great North East name) Hemy, are also known to have been painters.

A portrait of Thomas M. M. Hemy.

Photo Credit: Searle CanadaSo, what has all of this got to do with football? Well, his maritime paintings aside, one of Thomas Hemy’s best known works is a painting of a football match. This painting is considered to be the first oil painting of an Association Football match and dates to 1895. Football had featured in art prior to this in, for example, Thomas Webster’s painting Football or The Football Game, which dates to 1839. This painting did not, however, depict soccer, as the rules hadn’t been formulated at this time, but instead one of the numerous proto-football games that existed at this time.

This painting is interesting as, contrary to commentary regarding it on certain art history websites, the game portrayed in it is not one of the mass participation games of mob football. Neither is it one of the well-known public school games. It appears to be an informal but small-sided game, as it shows a group of approximately 20 players bearing down on a single, rather small, individual who appears to be acting as a goalkeeper.

‘Football’ by Thomas Webster, 1839.

Photo Credit: Ray PhysickThere, were, of course several artistic depictions of soccer prior to Hemy’s 1895 painting and, indeed, Hemy himself is known for a watercolour painting called Goal!, dating to 1885, and depicting an amateur game between a team wearing yellow and brown shirts and one wearing red shirts and navy blue ‘knickers’ (as they were known at the time), which was originally created for The Boy’s Own Paper. These earlier sketches, drawings and paintings were usually created, like Goal!, as illustrations to appear in publications of various kinds. This was not the purpose of Thomas Hemy’s famous oil painting of 1895.

The painting portrayed a game between Sunderland and Aston Villa, in January 1895, which was played at Sunderland’s Newcastle Road ground (they wouldn’t move to Roker Park until 1898) and finished in a four-all draw. Villa took the lead through Dennis Hodgetts after 15 minutes. James Gillespie equalised for Sunderland on 30 minutes.

Villa then took a 3-1 lead with a goal from Steve Smith and a Jack Reynolds penalty. Jimmy Hannah then pulled one back for Sunderland to make it 3-2 to Villa at half-time. Sunderland found an equaliser through Jimmy Miller after a little more than hour and went 4-3 up 20 minutes from the end through Gillespie’s second of the game. Villa had made it 4-4 by the 80th minute with a goal from Jack Devey.

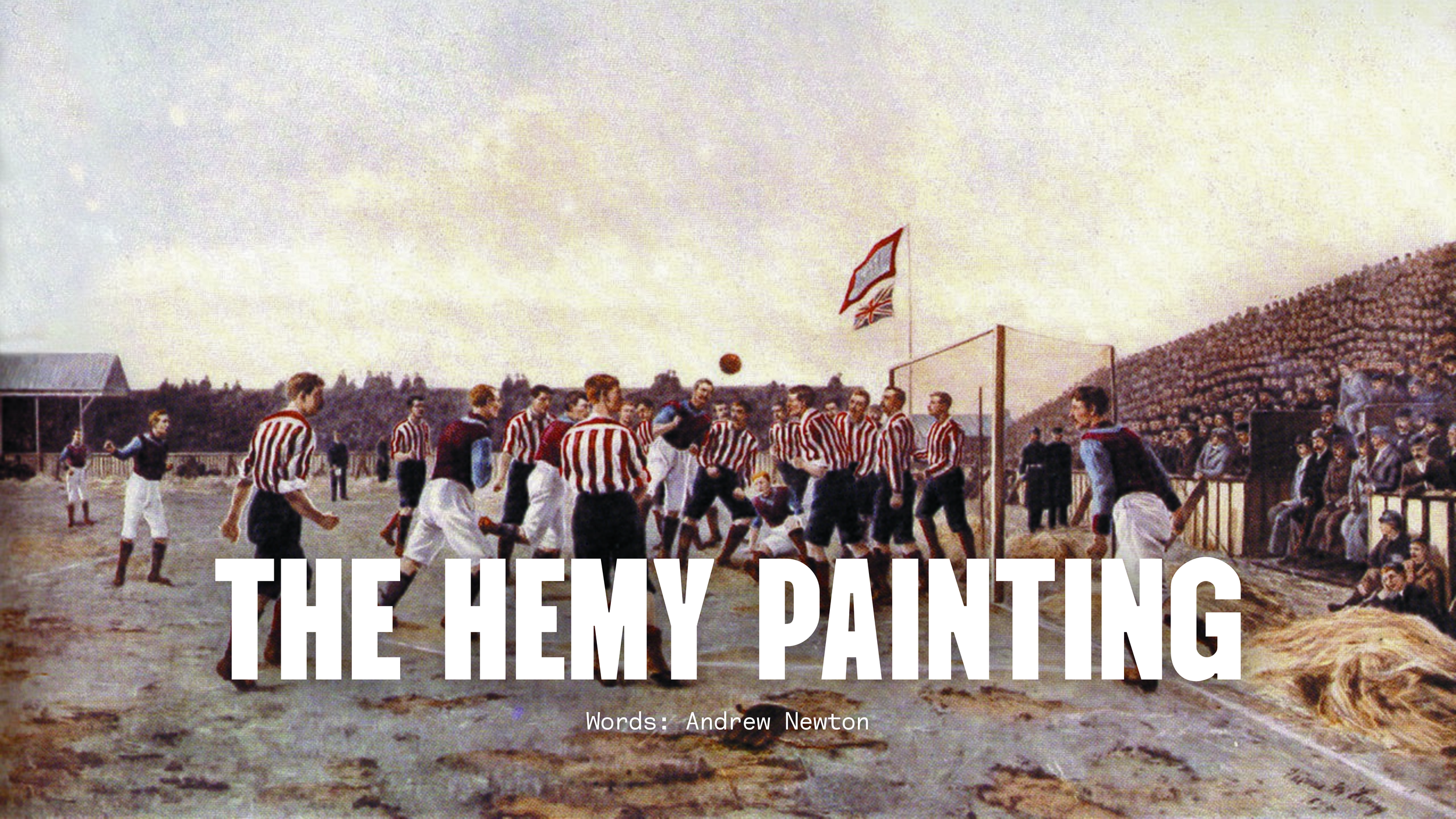

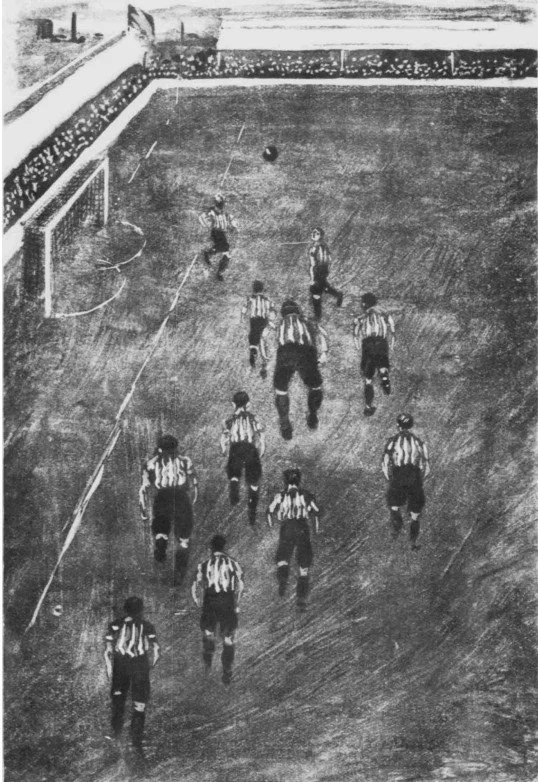

Hemy’s 1895 painting of Sunderland versus Aston Villa - ‘The Hemy Painting’.

Photo Credit: WikipediaThe painting is a large one, measuring 12 feet in length and 8.5 feet in height, making it possibly the largest painting of an Association Football match. It is displayed in an ornate gilded frame with the name of each player and official etched on individual pieces of ivory placed along the bottom of the frame in line with their relative position in the painting. Over the years, it has been known by several titles, including Sunderland v Aston Villa 1895, A Corner Kick, and The Last Minute-Now or Never. Despite this, it is generally referred to by Sunderland fans as ‘The Hemy Painting’.

It is widely suggested that the painting was commissioned by Sunderland AFC to celebrate winning three league titles in four seasons (1892, 1893, and 1895). We know that Thomas Hemy was in attendance at the Villa match on the 7th January 1895 as the Sunderland Echo’s edition of that date records him being so and recounts his conversation with their reporter. At this point, neither the club nor Hemy could have known for certain that Sunderland would win the title that season, so Hemy can’t have been commissioned to create a painting celebrating the 1895 title prior to his attendance at this game.

What is more likely is that the club, knowing of Hemy’s presence at this, and possibly other matches, asked him to create the painting, either from memory or from sketches (Hemy is known to have produced over 100 sketches of the scene), following the conclusion of the season. The Aston Villa game would have been an appropriate one to appear in such a commemorative work as Sunderland and Villa were great rivals during the late 19th century and were the country’s leading clubs at this time. Although it has been suggested in some quarters that Hemy just speculatively produced the painting and then offered it to the club for sale, it would seem unlikely that an artist would produce a work of this size and scale without a guaranteed buyer.

By 1898, it was being reported that Sunderland would hold a draw, with the painting and associated ‘proofs’ (presumably Hemy’s preliminary sketches) as the prize. At the club’s AGM on 11th July 1900, it was reported that the painting had been raffled but that no one had stepped forward to claim their prize. It was suggested that the painting might be donated to the Borough Art Gallery or the Town Hall, but no decision was taken and it remained in the premises of the furniture dealers where it was being stored.

By the 1920s, the painting was hanging in the grill room of The Bells Restaurant, Grill and Lounge at 14, Bridge Street, Sunderland. The proprietors of this establishment were James Henderson and Sons. J P Henderson, son of the owner of The Bells, had been chairman of Sunderland AFC at the time that the painting was produced. In 1929, Sunderland opened a new grandstand, designed by the renowned football stadium architect Archibald Leitch, at Roker Park. Now that the club had a space to house the painting it was presented to them by former chairman Samuel Wilson. To get to the new stand at Roker Park from Bridge Street, where it had been kept until this time, the painting had to cross another new addition to the Sunderland skyline; the brand new Wearmouth Bridge.

This bridge, which replaced an older version, accompanied the adjacent Monkwearmouth Railway Bridge which had been constructed in 1879, the year that the club was founded. From this point on, the painting remained at Roker Park until around 1990, when it was removed for cleaning and restoration and then subsequently displayed at the Sunderland Museum and Art Gallery. It was always intended that the painting would be displayed at the club’s new stadium. The reception area at the Stadium of Light was designed with this in mind and it hangs there now, behind protective glass, dominating the marbled main entrance atrium and looking magnificent.

The Hemy Painting hanging in the entrance foyer of the Stadium of Light.

Photo Credit: Chris Cummings ArtNot only is the Hemy painting a striking piece of art, but there are several things about it that people notice and comment on, and these are all historically interesting features. The first of these is that the painting contains eleven players wearing the famous red and white stripes of the Wearsiders. Seemingly Sunderland, who are defending, don’t have a goalkeeper, but this is not the case, he’s just dressed the same as everyone else. Goalkeepers were not required to wear a different colour to their teammates until the 1909/10 season and so, usually, wore the same shirt as the rest of the team with the only distinguishing feature being an occasional cap. It was, however, not unusual for goalkeepers to don different colours for international matches.

Another notable aspect of the painting is the strange pitch markings. The six yard box appears to be semi-circular. In fact, it consists of two equal and conjoining semi-circles. These are the result of an 1891 change to the rules of the game which formalised the goal kick. The rules stated “…the ball…shall be kicked off… within six yards of the goal-post nearest the point where the ball left the field of play”. These arcs were introduced to mark a six yard radius of each goalpost, indicating where a goal kick may be taken from.

At around the same time, penalty kicks were introduced and this led to the introduction of 18-yard and 12-yard lines both extending the width of the pitch. These marked the area in which a foul would result in the awarding of a penalty kick and the location, 12 yards from the goal line, from where the kick may be taken. A penalty kick could be taken at any point along this 12-yard line. Modern pitch markings were not introduced until 1902 and the penalty arc (the ‘D’ at the front of the penalty area) did not appear until 1937.

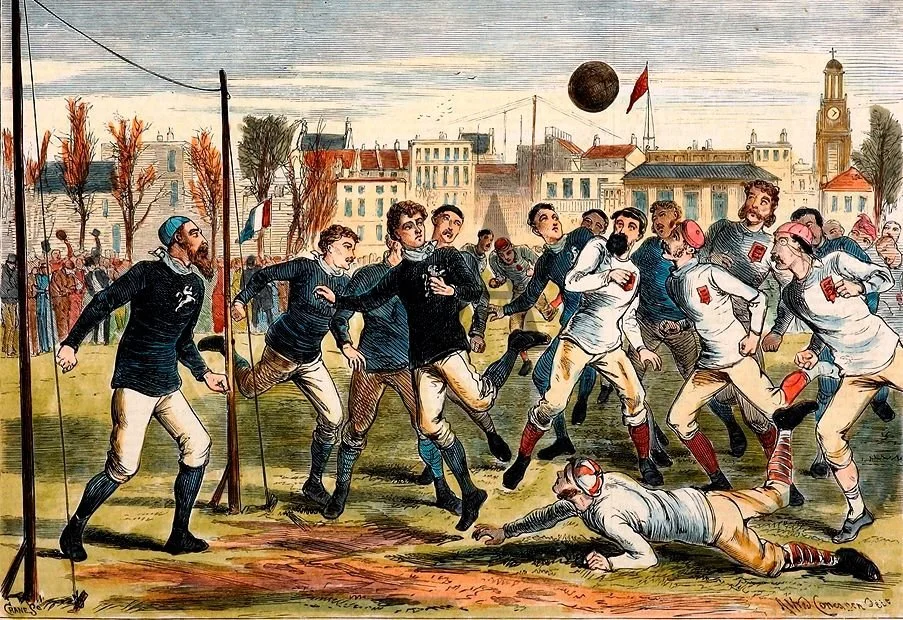

If you look closely at the players in the painting, they all appear to be making fists with their hands. It has been suggested that this is because Thomas Hemy was more familiar with painting ‘pugilists’, but there don’t appear to be any known paintings by Hemy of boxers or boxing matches. The pugilist theory is, therefore, hard to verify. Perhaps it’s just that our Thomas wasn’t very good at doing hands, which, let’s be fair, are really hard to draw. However, if you look at broadly contemporary illustrations of football matches- the drawing of the England v Scotland match at The Oval in 1879 is a good example- many of the players have clenched fists and display the same stiff-backed, upright stance of the players in the Hemy painting.

It’s possible that Victorian footballers all ran around in this awkward-looking posture but it is perhaps more likely that this is a stylistic choice. It seems that Hemy, and other Victorian artists, chose to depict players in a pose which, to them at least, portrayed the noble, manly vigour that was supposed to be embodied by Victorian sportsmen. This is perhaps a reflection of the concepts of ‘muscular Christianity’ and ‘muscular Judaism’, which were popular at the time. These linked physical fitness and athletic competition with moral and spiritual virtue.

Engraving of action during the England versus Scotland match at The Oval, 1879 which originally appeared in The Graphic.

Photo Credit: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 1879Keen students of the history of Sunderland AFC will also point out that the painting depicts piles of straw around the edge of the pitch. In the days before under-soil heating, straw was regularly used to insulate pitches in cold weather, to prevent them freezing. It is sometimes said that the piles of straw in Hemy’s painting are an eerie foreshadowing of one of the greatest scandals in Sunderland’s history which, as it occurred in the 1950s, he would have known nothing about.

Like the majority of clubs, Sunderland sought to find ways around the maximum wage rule that existed in English football between 1901 and 1961. In 1957, they were caught carrying out some creative accounting, hiding money for additional payments to players in their expenditure on straw to insulate the Roker Park pitch. This led to a variety of fines and bans for the individuals involved. The following season, Sunderland were relegated for the first time in their history and some older fans hold that the club have never really been forgiven for their crime.

The Hemy Painting is significant not just because it contains interesting historical details about the development of professional football (and about the early years of Sunderland AFC, and to a lesser extent Aston Villa); illustrations, engravings and lithographic impressions also captured such details from the early period of the game, prior to the widespread use of photography (which didn’t really appear in newspapers until the first years of the 20th century).

Its importance also lies in the fact that, despite the rapidly increasing popularity of football in the late 19th century, it is a subject that was largely ignored by fine artists. Indeed, according to sports historian Ray Physick (who wrote a fascinating PhD on the subject of representations of football in art), it was not until 1992 and the dawn of the Premier League that football came to be considered to be a suitable subject for art. This, of course, is a bit of a generalisation and Physick points to the work of L. S. Lowry, Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, Sybil Andrews, Carel Weight, Cecil Beaton, Nigel Henderson, and Peter Blake as exceptions to this rule.

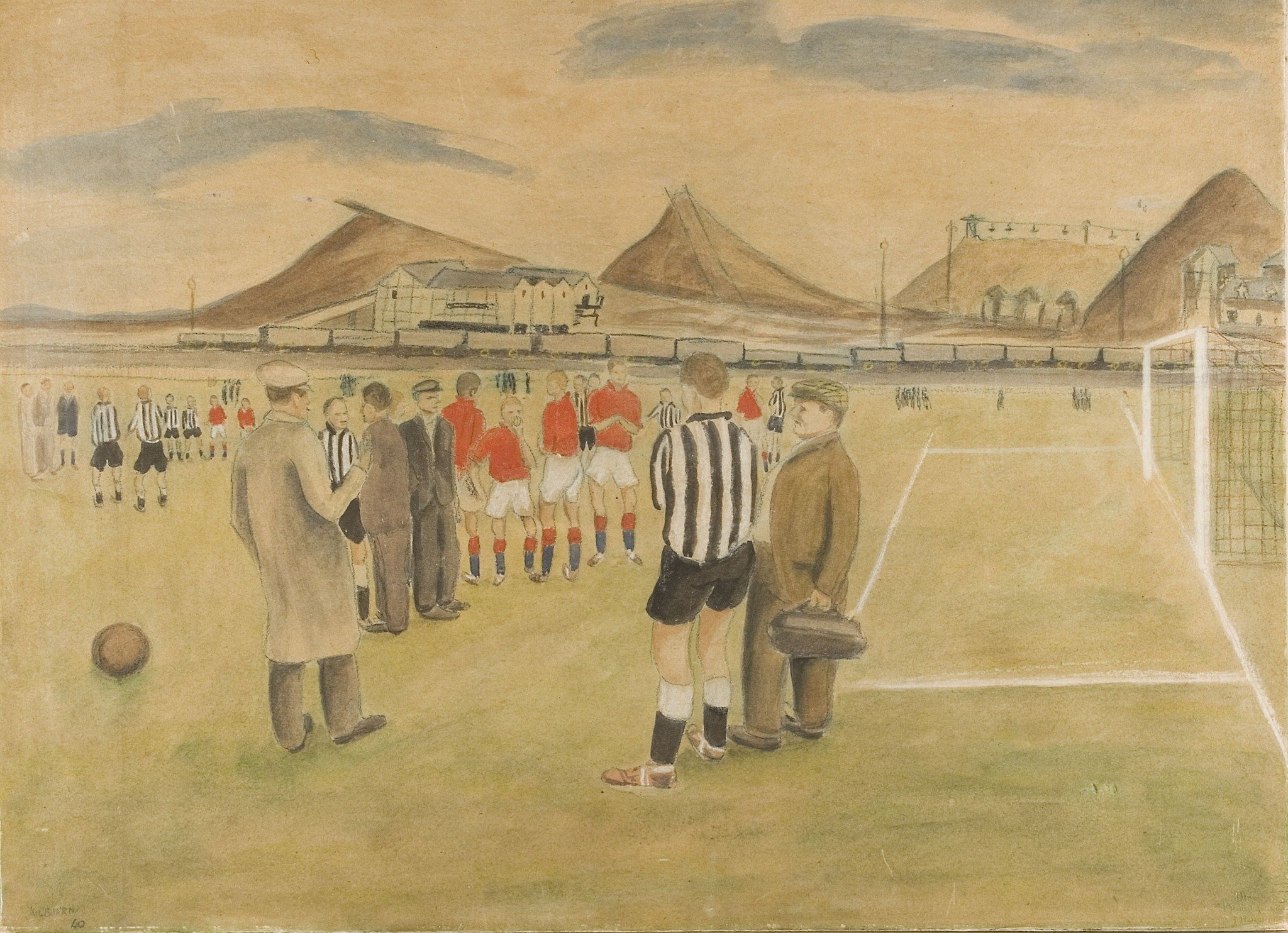

One of the most interesting artists to have used football as a subject for their paintings prior to 1992 is Oliver Kilbourn. Kilbourn was a founding member of the Ashington Group, sometimes known as the Pitmen Painters. This was a small society of artists based in Ashington, Northumberland most of who were mine workers in the Ellington and Woodhorn Collieries. The group originated as a branch of the Workers’ Education Association, a body set up in 1903 to provide further education to working adults. Beginning in 1927, the Ashington Group took evening classes in a variety of subjects before eventually deciding to study art appreciation. The WEA and Durham University arranged for the painter Robert Lyon to tutor them. The members quickly grew dissatisfied with the course and Lyon suggested that they took up painting themselves to develop their understanding and appreciation of art. This was highly successful and the Pitmen Painters’ work, showing life above and below ground in Northumberland’s coal mining districts, became famous.

Kilbourn’s 1938 painting Half Time at the Rec, depicts events at the midway point of a football match played at Ashington Recreation Ground. This was sporting venue established by the local collieries from 1886 onwards for local people to use. Upon opening, it had a gymnasium, a 771 yard bicycle track, a bandstand, a handball wall, a grandstand, and several football pitches.

Oliver Kilbourn’s 1938 painting ‘Halftime at the Rec’.

Photo Credit: Woodhorn MuseumAlthough it was the earliest depiction of football in art, the Hemy painting did have some near contemporaries. Two other oil paintings from the 1890s constitute early artistic representations of football. One of these is The Football Match by Clarence Bletherik, painted in 1897, and the other is J. W. T. Manuel’s Sheffield United-The Parade, which dates to 1899. Bletherik’s painting is in the tradition of realism but it appears that it is not possible to identify the ground at which the game depicted in it is being played. Manuel’s painting has been described as ‘an impressionistic piece’ which appears to be intended to demonstrate the ’patterns of movement of the players’.

Some critiques of these works suggest that Hemy’s painting does not capture the intensity of professional football but in Bletherik’s and Manuel’s work there is a sense of movement on the field of play. Art is, however, subjective and other assessments might consider Manuel’s painting, for example, to be naïve and childlike, lacking accuracy, depth and realism.

J. W. T. Manuel’s ‘Sheffield United-The Parade’, painted in 1899.

Photo Credit: Ray PhysickThe Last Minute-Now or Never, the ‘Hemy Painting’, is painted in a way that captures the event in a realistic style, albeit with some artistic licence (that stance of noble manly vigour and the terraces at the Newcastle Road ground appear to be slightly steeper than they were in reality). What is important about this is that this is the style of painting in which 19th century artists depicted important historical, military, social, and cultural events.

Good examples include Wellington at Waterloo by Robert Alexander Hillingford, Washington crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze, and Proclamation of the German Empire by Anton von Werner. Arguably, Hemy is treating the fixture between Sunderland and Aston Villa in a similar manner, as an event of some significance. With dimensions of 12 by 8 ½ feet and in its ornate, golden frame, the Hemy painting is grand, and perhaps a little pompous, but this would appear to be the point.

‘Wellington at Waterloo’ by Robert Alexander Hillingford, 1892.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsIt is meant to stand as a fitting tribute to the first club to win the English League title three times and to portray this achievement as being momentous and socially and culturally important. This is football being taken seriously, not just as an amusing diversion for former public schoolboys or a form of entertainment for the proletariat. This is football being favourably compared to spheres of human endeavour like politics, warfare, and science, which were all popular subjects for this type of art in the 19th century.

It is appropriate that Sunderland celebrated their historic third league title with a painting of their game against Aston Villa. In the years following the production of the Hemy painting, Villa would become the second club to win three league titles. In a reversal of these roles, Villa were the first club to win six league titles, and Sunderland the second.

It seems that Thomas M. M. Hemy, as well as being interested in maritime scenes, had an artistic interest in football, in the widest, Victorian, sense of the word. As well as the painting that now hangs in the Stadium of Light and Goal!, which was produced for The Boys Own Annual, Hemy painted The Eton Wall Game, which is dated to 1887, and Harrow School Footer Field, depicting the form of football played at Harrow School. In 1894, Hemy painted A Rugby Match, which depicts the Durham School 1st XV mid-scrum, playing against a team in red and white hooped shirts. There is something of a mystery surrounding who this team is.

Durham School’s rugby fixtures for that season do not mention any team known to have played in those colours. However, cross referencing of the painting with team photos of the time have allowed several well-known rugby players to be identified, including Graham Campbell Kerr, the Scotland international. Hemy is also known to have painted a cricket match at Rugby School.

‘The Proclamation of the German Empire’ by Anton von Werner, 1885.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia‘A Rugby Match’ by Thomas M.M. Hemy, 1894.

Photo Credit: Durham Cathedral Schools FoundationHemy’s interest in public school sports derived from the suggestion from a publisher that he could make money by painting scenes of the ‘great schools of England’, and he is known to have painted other aspects of life at Eton College. He found that this was a fairly saturated market and, endeavouring to find a niche, he enquired of pupils and staff members about their interests, which led him to produce scenes illustrating the characteristic traditions and games of these institutions. This experience in painting public school sports is, perhaps, what led to him painting a scene incorporating two of the great institutions of professional football.

Later in life, Hemy appears to have been living in London, at Belsize Studios, 4 Glenilla Road, Camden. This was an area of London that was home to a number of artists in this period. The building where Hemy lived still exists and is described as having a ‘bright and voluminous reception space, and quiet isolation’; perfect conditions for an artist. Thomas M. M. Hemy died on the Isle of Wight on 30th March 1937, the year after Sunderland won their historic sixth league championship and the same year that they would finally win the FA Cup.

Although not particularly widely known, ‘The Hemy Painting’ is hugely significant in the world of football, not just because it captures important details about the game at the end of the 19th century but because it, in its own right, marks a hugely important point in the history of the game- the moment that Association Football became a serious enough undertaking to be a subject for fine art.