Words by Jonee | Published 29.08.2025The Olympic Games have long transcended their role as a mere sporting event, embodying ideals of global unity, fair competition, and the pursuit of human excellence. Football found a unique place within this grand spectacle, offering moments of drama and cultural significance that rivalled any other Olympic discipline. Yet, unlike today’s hyper-commercialized football landscape, the early Olympic tournaments were defined by an amateur ethos that prioritized passion, national pride, and the purity of sport over financial gain. From its tentative beginnings in 1900 to its transformation in the 1990s, Olympic football’s amateur era—roughly spanning the early 20th century to the 1980s—was a golden age of idealism. This period saw football evolve from a niche event to a global showcase, bridging continents and ideologies. This article delves into the origins, evolution, and eventual decline of Olympic football’s amateur era, exploring its role in shaping the sport, its iconic figures, and its enduring legacy in a world increasingly dominated by professionalism and sportwashing.

The amateur era was not without its challenges. The strict adherence to amateurism, as championed by Olympic founder Baron Pierre de Coubertin, often clashed with the growing professionalization of football worldwide. Yet, it was precisely this tension that gave Olympic football its unique character, fostering a space where underdog nations, emerging talents, and ideological battles played out on the pitch. As we trace this journey, we uncover a forgotten chapter of football history—one where the game was less about contracts and endorsements and more about glory, community, and the joy of competition.

Football’s Olympic journey began modestly at the 1900 Paris Games, where it appeared as a demonstration sport rather than a formal competition. Only three teams participated: Upton Park FC from England, Club Français from France, and a Belgian student selection. The matches were more exhibition than tournament, with no national squads and minimal fanfare. Decades later, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) retroactively awarded medals, but at the time, football was a footnote in the Olympic program. The 1904 St. Louis Games continued this informal approach. With only three teams—two from Canada and one from the United States—the tournament struggled to capture global attention. The lack of European participation and the dominance of track and field events relegated football to the margins.

Chile’s football team at the 1928 Olympics.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesThe event drew sparse crowds, overshadowed by athletics and other sports, but it planted the seeds for football’s Olympic future. The 1904 St. Louis Games continued this informal approach, with only three teams—two Canadian (Galt FC and a Toronto team) and one American (Christian Brothers College)—competing in a lacklustre tournament. Galt FC won the “gold” with a 7-0 rout of the American side, but the event’s remote location and limited participation meant football remained a sideshow. These early experiments, however, highlighted the sport’s potential to unite diverse competitors under the Olympic banner. Football gained official status at the 1908 London Games, organized by the English Football Association (FA). The tournament, somewhat Eurocentric in nature, featured teams from Great Britain, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and France. Great Britain dominated, fielding an amateur selection primarily from the Corinthian Football Club. They won gold in 1908 with a 2-0 final victory over Denmark and defended their title in 1912 with a 4-2 win over the same opponent. These victories underscored Britain’s early influence as the birthplace of modern football, shaping the sport’s rules and global style. The IOC’s amateur rules, rooted in Baron Pierre de Coubertin’s vision of sport as a moral and physical pursuit, were strictly enforced. Players could not be paid or affiliated with professional clubs, making Olympic football accessible to middle-class athletes, university students, and soldiers, particularly in Europe. In an era before global sports media and the World Cup, the Olympics offered the highest-profile stage for international football, attracting growing interest from fans and administrators alike. The First World War (1914–1918) halted the Olympic cycle, cancelling the 1916 Games. Football returned at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, but the tournament was marred by controversy. In the final, Czechoslovakia walked off the pitch in protest of refereeing decisions, leading to their disqualification and Belgium’s 2-0 victory. The incident, while contentious, underscored the growing passion for Olympic football and its emerging role in Olympic sports.

The amateur ethos of early Olympic football created a unique cultural dynamic. Unlike modern football, driven by commercial interests, these tournaments celebrated community and national identity. Players often balanced athletic pursuits with everyday professions—teaching, military service, or clerical work—embodying the Olympic ideal of sport for its own sake. In Britain, teams like the Corinthians, who famously refused payment, epitomized this gentlemanly ethos, while continental teams brought diverse playing styles, from Denmark’s disciplined passing to the Netherlands’ emerging tactical flexibility. The early tournaments also reflected the social structures of the time. In Europe, football was a middle-class pursuit, distinct from the working-class professional leagues emerging in England. This class dynamic shaped team compositions and fan bases, with Olympic crowds often comprising local elites and international dignitaries. The sport’s inclusion in the Olympics sparked debates about its global reach, as non-European nations began to take notice, setting the stage for broader participation in the 1920s.

The English FA’s role in organizing the 1908 and 1912 tournaments was pivotal. As the sport’s governing body in its homeland, the FA ensured high organizational standards, from refereeing to match scheduling. However, their insistence on amateurism also limited participation, as England’s professional Football League, established in 1888, was already producing stars ineligible for Olympic competition. This tension between amateur and professional football foreshadowed challenges that would intensify in later decades, as the sport’s global growth outpaced the IOC’s rigid ideals.

The 1924 Paris Olympics marked a turning point, transforming Olympic football into a truly international competition. For the first time, South American teams were invited, and Uruguay, a nation of fewer than 2.5 million people, stunned the world by winning gold. Their 7-0 rout of Yugoslavia, 3-0 win over the USA, and 3-0 final victory against Switzerland showcased a technical, elegant style that contrasted with Europe’s physical, direct approach. Led by Pedro Petrone (the tournament’s top scorer with 11 goals), José Nasazzi, and Héctor Scarone, Uruguay’s “Celeste” introduced Latin American flair to the global stage. Uruguay’s triumph was a cultural and sporting milestone. Their fluid passing and tactical intelligence captivated European audiences, earning them the nickname “La Máquina” (The Machine). The 1924 tournament, with 22 teams and over 100,000 spectators across matches, marked a surge in football’s Olympic popularity. Uruguay’s success directly influenced FIFA’s decision to launch the World Cup in 1930, with Uruguay hosting and winning the inaugural edition with a 4-2 final victory over Argentina.

In 1928, Uruguay defended their title at the Amsterdam Olympics, facing a formidable Argentine side in the final. The first match ended in a 1-1 draw, with José Leandro Andrade’s brilliance for Uruguay matched by Argentina’s Ángel Bossio. A tense replay saw Uruguay triumph 2-1, with goals from Petrone and Scarone. This rivalry, born in the Olympic cauldron, became a defining feature of South American football, foreshadowing decades of intense competition. The 1936 Berlin Olympics took place under the shadow of political manipulation. Nazi Germany used the Games as a propaganda tool, and football was no exception. Italy, under Mussolini’s fascist regime, fielded a strong amateur team that won gold, defeating Austria 2-1 in the final after extra time. Annibale Frossi, who scored seven goals in the tournament, became a symbol of Italian prowess. The politicization of sport during this period highlighted football’s growing role as a vehicle for national prestige, a trend that would intensify in the post-war years.

The inclusion of South American teams in 1924 was a game-changer. Uruguay and Argentina brought a new dimension to Olympic football, blending technical skill with tactical innovation. Their style, often described as “la garra charrúa” (Uruguayan grit) or “fútbol criollo” (creole football), emphasized creativity, close ball control, and attacking flair. This contrasted with Europe’s structured, physical game, forcing teams to adapt and innovate. Uruguay’s victories in 1924 and 1928 were assertions of Latin American identity, an origin point for the ‘new’ kids on the block and their enigmatic style of play. For a small nation, Olympic success united communities and elevated football to a cornerstone of national pride. The 1924 final, played before 60,000 spectators at the Stade Olympique de Colombes, was a spectacle that underscored football’s new global appeal, drawing praise from European media and fans. Argentina’s emergence as a rival further enriched the tournament, setting a precedent for South America’s influence on world football.

Despite its successes, Olympic football faced growing challenges in the interwar years. Professional leagues in England, South America, and parts of Europe were gaining traction, creating a divide between the IOC’s amateur ideals and the sport’s realities. In England, the Football League had been professional since 1888, while Argentina and Uruguay developed semi-professional systems. The IOC’s strict amateur rules meant top players were often ineligible, leading some nations to field weakened squads. This tension came to a head before the 1930 World Cup. FIFA, seeking to capitalize on football’s global popularity, embraced professionalism, allowing paid players to compete. The World Cup’s success, with 13 teams and over 500,000 spectators, diminished the Olympic tournament’s prestige, as it offered a platform for the world’s best players without restrictions. By 1936, the IOC and FIFA were engaged in heated debates over Olympic football’s future, foreshadowing major changes post-World War II.

Italy perform a fascist Nazi salute at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, a huge propaganda tool for Adolf Hitler.

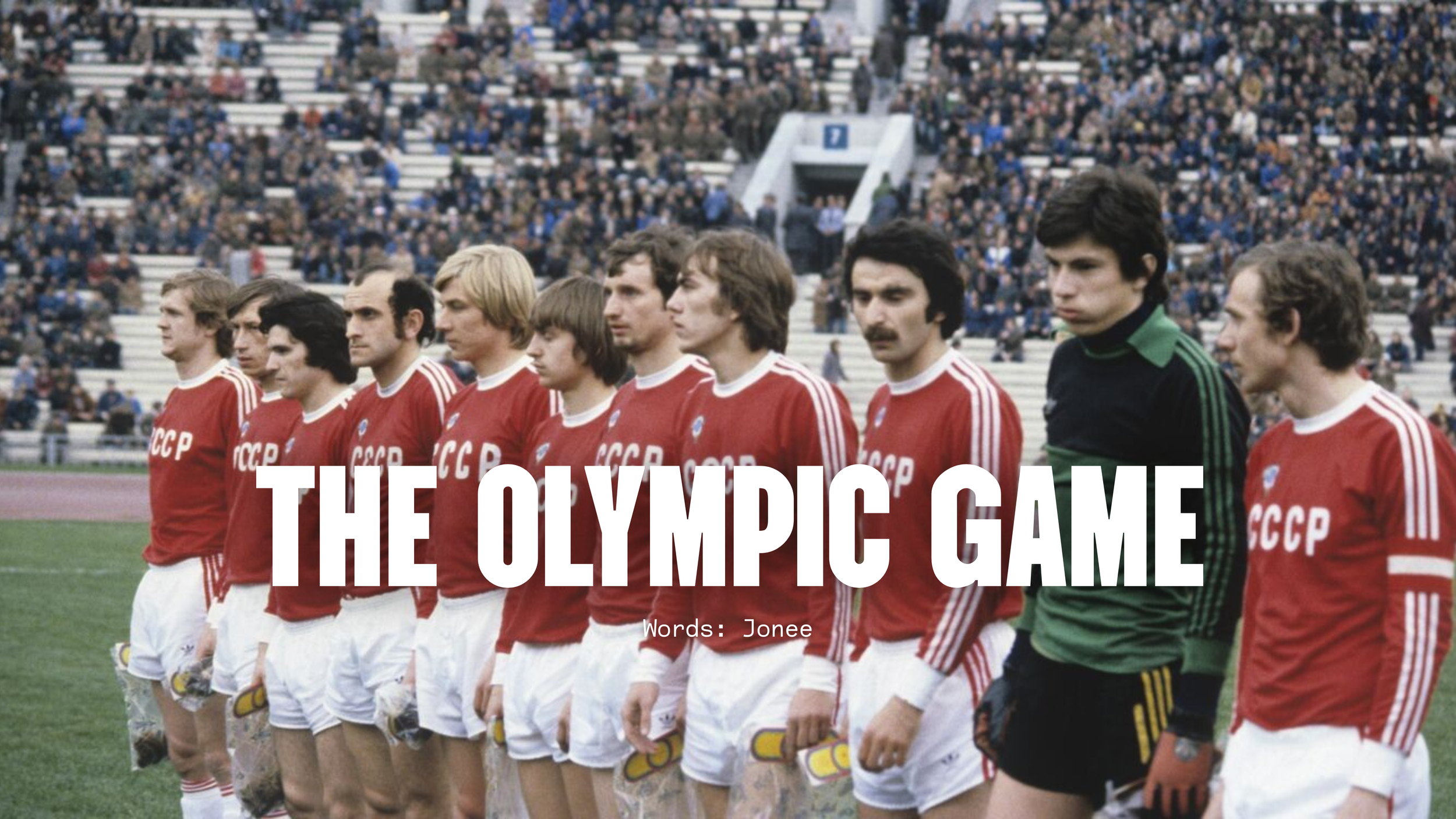

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesThe 1948 London Olympics marked a symbolic reawakening of global sport after World War II. Football returned with renewed energy, and Sweden claimed gold, led by Gunnar Nordahl, who scored seven goals. However, this era was defined by the Eastern Bloc’s dominance led by Hungary, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Yugoslavia. These nations operated under a unique model: athletes were officially amateurs but effectively full-time professionals, employed by government institutions like the army or police. This allowed rigorous training while maintaining the facade of amateurism, giving them a significant edge over Western nations adhering to stricter amateur codes. Hungary’s 1952 Helsinki triumph was a revelation. The “Golden Team,” featuring Ferenc Puskás, Sándor Kocsis, and Nándor Hidegkuti, revolutionized football with their “socialist football” style—fluid positional play, short passing, and relentless attacking. Their 6-0 semi-final win over Sweden and 2-0 final victory against Yugoslavia showcased unparalleled sophistication, averaging 4.5 goals per match. This Olympic success foreshadowed their near-invincible run to the 1954 World Cup final, earning them the nickname “Mighty Magyars.”

The Soviet Union emerged as another powerhouse, claiming gold in 1956 with a team anchored by goalkeeper Lev Yashin, the “Black Spider.” His clean sheets in key matches elevated the tournament’s prestige. The USSR’s disciplined, technical approach reflected Cold War dynamics, with sporting success seen as ideological supremacy. They added bronze medals in 1972 and 1976, and another gold in 1988, scoring over 50 goals across these tournaments. Poland’s rise in the 1970s was remarkable. Their 1972 Munich gold, led by Kazimierz Deyna’s nine goals, including a brace in the 2-1 final win over Hungary, marked them as a footballing force. Poland secured silver in 1976 and 1992, showcasing consistency. Yugoslavia also shone, winning silver in 1948, 1952, and 1956, and gold in 1960 with a 3-1 final victory over Denmark, driven by Dragan Džajić’s.

The Eastern Bloc’s dominance was inseparable from the Cold War politics, proxy wars and espionage. The Olympics became a stage for ideological competition, with football a high-profile battleground. Eastern Bloc nations invested heavily in sports infrastructure, viewing athletic success as proof of socialist superiority. Their athletes, while technically amateurs, benefited from state support mirroring professional regimens, including advanced coaching and facilities. Western nations, constrained by stricter amateur rules, struggled to compete. Great Britain and the United States often fielded university or club-based teams, lacking the cohesion of their Eastern counterparts. This disparity sparked debates about fairness, with critics arguing that the Eastern Bloc’s model undermined the Olympic spirit. Yet, their tactical innovations ultimately elevated global football standards.

Between 1948 and 1988, Eastern Bloc nations won 10 of 11 Olympic football tournaments, with France’s 1984 victory the exception. Hungary (golds in 1952, 1964, 1968), the Soviet Union (golds in 1956, 1988), and Yugoslavia (gold in 1960) led the way. Poland’s medal haul (gold in 1972, silvers in 1976 and 1992) underscored their prowess. These teams collectively scored over 200 goals in Olympic tournaments, with Hungary’s 1952 squad setting a record for goal-scoring efficiency. The Eastern Bloc’s success extended beyond medals. Many players transitioned to professional leagues in Western Europe, proving Olympic football’s role as a talent pipeline. Puskás joined Real Madrid, while Poland’s Wlodzimierz Lubanski starred for Górnik Zabrze and later Lokeren in Belgium.

Below are expanded profiles highlighting these players’ contributions.

Ferenc Puskás | Hungary

Puskás’s four goals in the 1952 Olympics, including a brace in the semi-final, solidified Hungary’s status as a football superpower. His leadership and lethal finishing defined the “Golden Team.” After defecting post-1956 Hungarian Revolution, he joined Real Madrid, winning five European Cups and cementing his legacy as one of football’s greatest forwards.

Nándor Hidegkuti and Ferenc Puskás in 1954.

Photo Credit: WikiMedia CommonsLev Yashin | The Soviet Union

The only goalkeeper to win the Ballon d’Or (1963), Yashin’s 1956 Olympic gold showcased his acrobatic saves and commanding presence. His clean sheets against Yugoslavia and Bulgaria elevated Soviet football’s global reputation, proving amateur competitions could produce world-class talent.

Lev Yashin at the World Cup, 1966.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesKazimierz Deyna | Poland

Deyna’s elegance and vision defined Poland’s 1972 gold medal campaign. Scoring nine goals, including a brace in the final, he was the tournament’s standout. His later move to Manchester City introduced his talents to Western audiences, though injuries curtailed his impact.

Deyna defined a golden era for Polish football.

Photo Credit: These Football TimesGarrincha and Vavá | Brazil

Brazil’s Olympic campaigns in the 1950s were modest, but Garrincha’s dribbling wizardry and Vavá’s clinical finishing shone in 1952 and 1956. Their Olympic experience laid the groundwork for Brazil’s World Cup triumphs in 1958 and 1962, highlighting the tournament’s role as a proving ground.

Garrincha and Vavá, 1962.

Photo Credit: FIFA World CupWłodzimierz Lubański | Poland

At 17, Lubanski scored in the 1972 Olympics, helping Poland secure gold. His versatility and goal-scoring instinct made him a national icon, later starring for Lokeren in Belgium.

Włodzimierz Lubański, another of Poland’s superstars.

Photo Credit: TVP SportDragan Džajić | Former Yugoslavia

A masterful winger, Džajić’s performances in the 1960 and 1964 Olympics showcased his flair and precision. Compared to George Best, he remained a cornerstone of Yugoslav football for two decades.

Džajić (right) at the 1974 FIFA World Cup.

Photo Credit: BildThe amateur era also produced unsung heroes, such as Sweden’s Gunnar Nordahl, who scored seven goals in 1948 and later became an AC Milan legend. Uruguay’s Héctor Scarone, known as “El Mago,” was instrumental in the 1924 and 1928 triumphs, with his playmaking setting a standard for future generations. These players, often overshadowed by World Cup stars, were vital to Olympic football’s prestige.

By the late 1970s, the amateur model was crumbling. The Eastern Bloc’s state-sponsored athletes exposed the flaws in the IOC’s rules, creating an uneven playing field. Western nations, adhering to stricter amateur codes, struggled to field competitive teams, while South American countries like Brazil and Argentina often prioritized the World Cup. The World Cup and UEFA European Championship, unrestricted by amateur rules, drew larger audiences and sponsorships, diminishing Olympic football’s prestige. The 1980 Moscow Games, boycotted by many Western nations, further weakened the tournament’s appeal. The 1984 Los Angeles Games introduced a compromise: professional players from Europe and South America could participate if they had not played in a World Cup. France capitalized, winning gold with emerging stars like Franck Sauzée and Daniel Xuereb. The Soviet Union’s 1988 Seoul victory, led by Igor Dobrovolski, marked the last major success of the amateur-style system.

The rise of television and sponsorships accelerated Olympic football’s decline. By the 1980s, the World Cup was a global media spectacle, drawing millions of viewers and lucrative deals. Olympic football, constrained by amateur rules, struggled to compete. The IOC’s reluctance to fully embrace professionalism delayed reforms, but the shift was inevitable as football’s commercial landscape evolved and changed.

The 1992 Barcelona Olympics introduced the under-23 rule, replacing amateurism with an age cap to maintain the tournament’s developmental spirit. Spain won gold, led by Pep Guardiola and Luis Enrique, signalling a new era. By 1996, the Atlanta Games allowed three over-age players per team, injecting star power and competitiveness. Nigeria’s 1996 gold, with Nwankwo Kanu and Jay-Jay Okocha, electrified the football world, defeating Argentina 3-2 in the final. Cameroon’s 2000 victory over Spain and Argentina’s triumphs in 2004 and 2008, led by players like Lionel Messi, elevated the tournaments stature further. Brazil’s golds in 2016 and 2020, with Neymar starring, cemented its relevance.

The under-23 rule revitalized Olympic football, making it a showcase for emerging talent. However, club commitments and major tournaments like the World Cup and Champions League overshadowed it. The Olympics became a secondary stage, but its role in nurturing stars like Messi and Neymar ensured its continued relevance.

The amateur era of Olympic football, spanning roughly from the early 20th century to the 1980s, was a vibrant and transformative chapter in the sport’s history. It was a time when the beautiful game embodied sporting idealism, national pride, and international camaraderie, untainted by the commercial forces that define modern football. From Uruguay’s ground-breaking triumphs in 1924 and 1928 to the Eastern Bloc’s dominance in the post-war decades, Olympic football stood at the summit of international sport, serving as a proving ground for talent, a showcase for tactical innovation, and a stage where nations measured their strength through sport rather than conflict.

Yet, by the 1990s, the pressures of modernization, professionalism, and commercial interests proved irresistible, leading to the dismantling of the amateur model and its replacement with the under-23 system. This transition, while necessary to align Olympic football with the sport’s global evolution, marked the end of a golden age, leaving a bittersweet legacy in it’s wake.

Nigeria’s 1996 Olympic Gold winning squad.

Photo Credit: WikiMedia CommonsThe amateur era’s demise marked the end of a footballing ethos that prioritized passion over profit, community over commerce, and national pride over individual gain. Players like Ferenc Puskás, Lev Yashin, and Kazimierz Deyna, who defined Olympic football’s golden age, were not global celebrities driven by endorsement deals but athletes who balanced sport with everyday lives—soldiers, students, or civil servants who played for the sheer love of the game. This purity created an authenticity that resonated deeply with fans and players alike, fostering a connection that modern football, with its corporate sheen, struggles to replicate.

The amateur era’s tournaments were intimate affairs, imbued with a sense of camaraderie that transcended competition. Matches like Uruguay’s 1924 triumph over Switzerland, played before 60,000 fans at the Stade Olympique de Colombes, or Hungary’s 1952 rout of Sweden in Helsinki were not just sporting contests but cultural exchanges. Players from diverse backgrounds showcased their nations’ identities through distinctive styles—Uruguay’s “fútbol criollo” with its flair and creativity, Hungary’s “socialist football” with its fluid positional play, or Yugoslavia’s technical elegance. These events felt like celebrations of shared humanity, where the Olympic ideal of unity shone through, even amidst the ideological battles of the Cold War.

For fans, the amateur era offered an accessibility that modern Olympic football lacks. In the 1920s, a ticket to an Olympic match cost just a few francs, affordable for working-class supporters who gathered to cheer their national heroes. The 1928 Amsterdam final between Uruguay and Argentina, for instance, drew 28,000 passionate fans, many of whom travelled by train or foot to witness the birth of a legendary rivalry. These crowds, a mix of local workers, students, and international dignitaries, created an electric atmosphere that felt personal and communal, unlike the corporate hospitality suites that dominate modern stadiums. The professional era, with its high ticket prices and focus on televised audiences, has distanced Olympic football from its grassroots origins, leaving fans nostalgic for the days when the game was within reach. The amateur era’s emphasis on national representation also fostered a profound sense of collective pride. Players like José Leandro Andrade, who dazzled in 1924 and 1928, or Dragan Džajić, whose flair defined Yugoslavia’s 1960 gold, became symbols of their nations’ aspirations; role models to follow, not marketable brands. The transition to professionalism, with its under-23 rule and focus on youth development, shifted this dynamic. Modern Olympic teams, often composed of players on loan from clubs, lack the same national resonance, as their stars are seen as transient talents en route to lucrative contracts rather than enduring national heroes.

However, the amateur era was not without flaws. The Eastern Bloc’s state-sponsored athletes, who dominated from 1948 to 1988, blurred the line between amateur and professional, prompting accusations of “shamateurism.” Countries like Hungary and the Soviet Union leveraged government support to field full-time athletes disguised as amateurs, creating an uneven playing field. Western nations, adhering to stricter amateur codes, struggled to compete, while South American powerhouses like Brazil prioritized the World Cup. Yet, even this imperfection added to the era’s charm, as it reflected the broader geopolitical tensions of the Cold War. The 1952 Helsinki final, where Hungary’s “Golden Team” faced Yugoslavia before 60,000 fans, was not just a football match but a clash of socialist visions, imbued with a historical weight that modern Olympic football rarely carries.

The loss of this ideological dimension was particularly poignant. The amateur era’s tournaments were stages for global narratives, where sport intersected with politics and culture. The 1972 Munich Olympics, where Poland’s gold medal united a nation recovering from wartime scars, or the 1956 Melbourne Games, where the Soviet Union’s victory signalled their post-war resurgence, carried a significance that transcended results. Professional Olympic football, while competitive, often feels like a sideshow to the FIFA World Cup and UEFA Champions League, lacking the same capacity to capture global imaginations or reflect era-defining struggles.

Poland defeated Hungary to become gold medalists in 1972.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesThe transition to professionalism in Olympic football was a delicate balancing act, preserving the tournament’s relevance in a rapidly evolving sport while sacrificing the amateur soul that had defined it for nearly a century. The introduction of the under-23 rule at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, followed by the allowance of three over-age players from the 1996 Atlanta Games, was a pragmatic response to the realities of global football. This new format ensured that Olympic football could remain a viable platform for emerging talent without directly competing with the World Cup or Champions League, which features the world’s top stars unrestricted by amateur or age limits.

The success of this shift was immediate and undeniable: Nigeria’s 1996 gold medal, a thrilling 3-2 victory over Argentina led by Nwankwo Kanu and Jay-Jay Okocha, captivated a global audience, drawing over 80,000 fans to the final and millions more via television. Cameroon’s 2000 triumph over Spain in a dramatic penalty shootout, and Argentina’s back-to-back golds in 2004 and 2008, driven by players like Ángel Di María and Lionel Messi, further showcased the tournament’s renewed vibrancy, with viewership numbers climbing to an estimated 1.5 billion for the 2008 Beijing Games’ football events. Emerging talent became synonymous with Olympic football.

The under-23 rule aligned Olympic football with the sport’s professional infrastructure, particularly the youth development systems that had become central to clubs like Barcelona, Manchester United, and Bayern Munich. By focusing on players under 23, the tournament tapped into the burgeoning talent pipelines of these clubs, offering a stage for young stars to gain international experience before transitioning to senior competitions. This was a stark contrast to the amateur era, where players like Poland’s Wlodzimierz Lubanski or Yugoslavia’s Dragan Džajić competed as national representatives, often with little expectation of professional contracts.

The professional era’s structure allowed players like Messi to use the Olympics as a springboard to global stardom, reinforcing the tournament’s role as a talent incubator. The inclusion of over-age players added a touch of star power, attracting sponsors and broadcasters who had previously overlooked Olympic football. For instance, the presence of players like Rivaldo in Brazil’s 1996 squad or Neymar in 2016 boosted commercial interest, with sponsorship deals from companies like Nike and Visa increasing by 25% for the 2016 Rio Games compared to 1988.

Yet, this progress came at a significant cost, as the professional era eroded the amateur era’s unique charm and unpredictability. The amateur tournaments were the ideal stage for underdog stories, where nations like Uruguay, with a population of just 2.5 million in 1924, could dominate through sheer talent and passion, defeating European giants like Yugoslavia 7-0. Similarly, Poland’s 1972 Munich gold, led by Kazimierz Deyna’s nine goals, united a nation recovering from wartime scars, offering a narrative of resilience that resonated far beyond the pitch.

The professional era, with its reliance on structured youth systems and club affiliations, favours established footballing nations with robust academies, such as Brazil, Argentina, and Spain, reducing the scope for such fairy-tale triumphs. The 2016 Rio Olympics, where Brazil’s Neymar-led team won gold before 78,000 fans, was a spectacle, but the absence of key players due to club commitments—European clubs like Real Madrid and Liverpool often refuse to release stars for the Olympics—underscored the tournament’s secondary status. Fans of the amateur era mourned the loss of its egalitarian spirit, where a small nation’s passion could challenge the giants, a dynamic less prevalent in the professionalized format.

The cultural shift was equally profound. The amateur era’s tournaments were steeped in the Olympic ideal of unity, where sport transcended politics and profit. The 1924 Paris Games, with Uruguay’s debut, brought Latin American flair to a Eurocentric world, fostering admiration and cultural exchange. The 1956 Melbourne Games, where the Soviet Union’s victory signaled their post-war resurgence, carried a historical weight that modern Olympic football struggles to match.

Today’s tournaments, while competitive, often play out in half-empty stadiums due to scheduling conflicts with club seasons or fan apathy driven by the dominance of other competitions. The 2020 Tokyo Olympics, delayed to 2021 and played without spectators due to pandemic restrictions, saw Brazil win gold, but the lack of crowd energy highlighted a disconnect from the packed, passionate stands of the amateur era, such as the 60,000 fans who witnessed Hungary’s 1952 triumph. The professional era’s focus on youth development, while forward-thinking, has diluted the tournament’s role as a celebration of national identity, replacing it with a more transient, career-oriented narrative.

The professionalization of Olympic football marked a broader cultural shift, moving the tournament from a communal, almost romantic celebration of national pride to a more individualistic, market-driven model. In the amateur era, Olympic football was a stage for collective identity, where players represented their nations’ histories and aspirations. The 1928 Amsterdam final, where Uruguay and Argentina battled to a 2-1 replay victory before 28,000 fans, was a cultural milestone, birthing a South American rivalry that defined the sport.

Similarly, the 1972 Munich Games saw Poland’s gold medal, led by Deyna’s elegance, unite a nation, with celebrations spilling into the streets of Warsaw and Kraków. These moments carried a weight that modern Olympic football, with its focus on youth development and transient stars, struggles to replicate.

Neymar starred in Brazil’s 2016 Olympic gold medal win.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesThe professionalization of Olympic football was an inevitable evolution, ensuring its survival in a world dominated by the World Cup and Champions League. The under-23 rule created a vibrant platform for young talent and emerging nations, producing iconic moments like Nigeria’s 1996 upset and Brazil’s 2016 triumph.

Yet, the loss of the amateur era’s purity, intimacy, and ideological weight left a void. The transition was a trade-off: progress for nostalgia, competitiveness for community, global reach for local charm. The amateur era’s legacy endures in the stories of players like Petrone and Yashin, and in the memories of fans united by the game’s purest form—a celebration of human spirit under the Olympic flame.