Words by Andrew Newton | Published 29.10.2025Many good stories start in a bar, so I’m going to start this one in a bar, but probably not in the kind of bar you’re imagining that a story about the early history of football would start in. No, this one starts in my favourite bar in Las Vegas. I’m not going to tell you its name because I don’t want you turning up and stealing my seat, but I will tell you that it’s known for flair bartending and some of the greatest flair bartenders in the world work, or have worked, there.

Anyway, early one afternoon a couple of years ago, my wife and I were chatting to one of the up and coming bartenders (bartending in bars like this is nothing like pulling pints in your local Wetherspoons), when the conversation turned to sport. One of the bar backs, who’d been half joining in the conversation, piped up and said “You know why it’s called football, don’t you?”, referring to the gridiron game played on that side of the Atlantic. I said, “Well, I know why, but I suspect you’re going to tell me something different”.

He asked what I thought and I explained about early forms of ‘Soccer’ and Rugby, which would have both been referred to as ‘football’, being played at America’s Ivy League universities and the gradual, and deliberate, evolution of their own set of rules for ‘football’.

“No”, he said, “It’s because the ball is a foot long”. Which, of course, is not the reason. In fact, it’s almost as infuriatingly wrong as when people believe ‘backronyms’, like club sandwich stands for chicken and lettuce under bacon (it doesn’t of course, in case I need to point this out).

Not only is it not the reason, but this explanation doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. The specified length of an American Football is between 11 and 11.25 inches, which clearly isn’t a foot. Interestingly, a regulation sized Rugby Union ball is between 11 and 12 inches in length. So, if we’re using the dimensions of the ball to name sports, Rugby Union is more deserving of the name ‘football’ than the American game. It’s possible that this pseudo-explanation is a result of an argument I’ve seen many fans of the round ball game make about American Football; “how can a game that is played 95% with the hands be called football?”

What this conversation made me realise is that, despite various forms of football being amongst the world’s most popular sports, many of the public are unaware of the origins of these games, their relationships to one another, and how they became the games that we know today.

First of all, let’s look at the term ‘football’ and some of the other names that the game is known by. As we all know, there are various games named football, Association Football being just one of them. Others include Rugby Union, Rugby League, American Football, Australian Rules, and Gaelic Football, and most of these are related or connected to each other to a greater or lesser extent. Up until about the 1960s, British newspapers would publish lists of football results and these lists would be subdivided in to “Association”, “Rugby Union” and “Rugby League”.

Interestingly, I recently came across an American newspaper article, from the Buffalo Evening News of the 28th June 1927, which referred to “soccer football”. The term ‘football’ was widely used as the colloquial term for either form of rugby throughout the UK until at least the First World War. Until quite recently, commentators on televised Rugby League games would regularly refer to the sport as ‘football’. Using the term ‘football’ solely for the Association rules version of the game is a fairly recent thing.

This is why some football clubs qualify which set of rules they play in their official names, for example London Welsh RFC, Nottingham RFC, St Helens RFC, Sunderland AFC, Bradford City AFC, and AFC Bournemouth. With the ‘R’ obviously standing for Rugby and the A for Association. Others, of course, don’t bother including such things, so we have Chelsea FC, the Barbarian FC, Harlequins FC, West Ham United FC, which, unless you’re in the know, you could believe played either version of the game. Some rugby clubs go even further, adding an ‘L’ or a ‘U’ to indicate which version of rugby they play.

The Victorians considered ‘soccer’ and Rugby to be variations of the same thing, for the very good reason that that is exactly what they are. Victorian participants in football developed slang terms to distinguish between the different codes. The Oxford University terms became the most widely used. Oxford slang often involved the shortening of a term, plus the addition of ‘-er’, from which we get the terms fiver and tenner to refer to five and ten pound notes.

The football related terms became rugger for rugby and for the Football Association rules, the word ‘Association’ was adapted to assoccer and then soccer. ‘Soccer’, therefore, is an English term and, as much as I’ve encountered Americans who think using the term winds us up, is not offensive to Englishmen (or anyone else from the UK). The man usually credited with inventing the term ‘soccer’ is Charles Wreford-Brown who, according to tradition, used it in response to an 1863 invitation from a group of his fellow Oxford students to join them in a game of ‘rugger’. It’s likely, however, that this story is more myth than reality.

Charles Wreford-Brown, Oxford Student and the supposed originator of the term ‘soccer’.

Photo Credit: WikiMedia CommonsThese different forms of football did not emerge fully-formed in the 19th century, they were the results of a convoluted process of evolution. They are descendants of a wide variety of broadly similar games that were played in north-western Europe or, more specifically, the British Isles, from at least the medieval period onwards. When people think of medieval football, they often think of the famous games of mob football, some of which are still played annually in places like Ashbourne in Derbyshire, Alnwick in Northumberland, and Kirkwall in Orkney.

A similar game to these, called Cnapan, was also played in the western counties of Wales. It involved large numbers of people, usually the majority of the male population from two neighbouring parishes. The object of the game was to take a ball, slightly larger than a cricket ball, which had been soaked or boiled in oil or animal fat to make it harder to handle, to the church of your own parish, using any means necessary.

La Soule, was another similar game, played in France. It also pitted parishes against one another and required a ball, or soule, to be transported to a particular location, often your own parish church, or your opponents’ parish church. There are indications that, occasionally, more than two parishes might compete in the same game. The soule could be made of wood or leather stuffed with materials such as horse hair, bran, moss, or hay. This game could be played with or without sticks to propel the ball, making it sometimes similar to hurling in Ireland. La Soule was a popular game and quite widely played.

It was also, like the other forms of mob football, a quite aggressive contest that often led to injuries occurring to the participants. As the game increased in popularity, some of its rules were standardised. For example, in 1412, it was decreed that the ball should be small enough to hold in one hand. The game appears to have been played in both rural and urban settings. Its practice had become very limited by the 19th century and the last recorded games were probably played sometime between 1930 and 1945. However, since 2011, a championship involving six teams has been held in Normandy.

The Ba’ Game, Kirkwall, Orkney. A still—practiced form of mob football in the modern world.

Photo Credit: The OrcadianAll of these games of mob football were associated with special occasions, such as holy days or even weddings. Games of football were played much more regularly than this in the medieval and post-medieval periods but even some of the best and most well-known books on the history of football concentrate solely on these large, violent, mass-participation games. While these books, and their esteemed authors, are correct in saying that games played in the British Isles are the progenitors of the modern codes of football, it is a variety of games played on smaller scale, but probably more regularly than mob football, that the modern games originate from.

The first recorded description of a game considered to be football comes from the 12th century. William Fitz Stephen was the personal household clerk to Thomas Becket, Lord Chancellor, Archbishop of Canterbury, and later sanctified as St Thomas of Canterbury. In 1174, Fitz Stephen, in his work Descriptio Nobilissimae Ciuitatis Londinae, recorded the popularity of football in London, stating that ‘after luncheon all of the young men of the city go out into the fields to play at the famous game of ball’. The description is, however, quite vague and could even relate to a hockey- or hurling-like game.

A similar reference to young men playing ‘ball’ comes from 1280. During a game at Ulgham in Northumberland, Henry, son of William de Ellington, received an accidental wound from a knife worn at the belt of David le Keu when a group of players collided. While we can’t be certain that the game being played was a form of football, the circumstances in which Henry received his injury could conceivably be the type of thing that would happen during a game of this kind.

A game referred to as football was certainly being played in London in 1314 when Nicolas de Farndon, Lord Mayor of the City of London, issued a decree banning it. In 1363, football is mentioned, amongst other games and sports, in an edict issued banning them in favour of archery, which was important to the defence of the realm.

Although the young men of London, who were banned from playing football in 1314, may have played to a fairly common set of rules particular to the area, there was no standardisation and the games varied from place to place. In some places handling was allowed, while in others it wasn’t; some games required the ball to be driven between two upright stakes, in others the ball had to be propelled across a line extending the width of the playing area.

The ball used in these games also varied quite widely, although it has been suggested that in locations where handling formed the predominant aspect of the game, balls were harder and possibly smaller, whereas balls tended to be larger and made of softer materials, or inflated, in areas where the focus of the games was on kicking.

From at least the 14th century, until around the 18th century, a game known as ‘camp-ball’ was played in Essex, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, and Suffolk. This had a complex set of rules and was played on specialised playing fields, referred to as ‘camping closes’. Teams consisted of between 10 and 15 players and the ball was approximately the size of a cricket ball. It appears that the ball was mostly carried and when a player was caught in possession, he was required to throw it to a team mate.

Players referred to as ‘sidemen’ acted in a similar way to blockers in American Football, attempting to keep would-be tacklers away from the man in possession. A ‘notch’, or ‘snotch’, was recorded when one team managed to carry or throw the ball through the goals. Despite the apparent lack of kicking involved in this game, it was described as a form of ‘foott balle’ in the Promptorium parvulorum, the first English-Latin dictionary, compiled in 1440, possibly by Geoffrey the Grammarian, a friar who lived in the vicinity of Lynn, Norfolk. A very similar game, known as ‘hurling to goals’ was played in Cornwall and lives on as an annual tradition in St Columb Major and St Ives.

It seems that football of some form was being played in the Stirling area in the mid-16th century. The Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum contains the world’s oldest football. This was recovered from the roof of Stirling Castle in 1981 and it is believed that it somehow became lodged in the rafters of the Queen’s Chamber during James V’s reconstruction of the castle between 1537 and 1542. There is also documentary evidence from Stirling during this period consisting of an order to “buy fut ballis to the King”.

The World’s oldest football. Found in the rafters of Stirling Castle and dated to between 1537 and 1542.

Photo Credit: The BBCShakespeare mentions football in both King Lear and The Comedy of Errors, suggesting that the game was well known amongst the general population. In King Lear, the Bard refers to ‘base football players’, suggesting that his opinion of the game and its participants wasn’t good. In The Comedy of Errors, Dromio ask Adriana “Am I so round with you as you with me, that like a football you do spurn me thus?”. An archaic meaning of ‘spurn’ is ‘to kick’, possibly suggesting that the version of football that Shakespeare was most familiar with was predominantly a kicking game.

In a publication dated to 1581, Richard Mulcaster, headmaster of Merchant Taylor’s School in 1561 and of St Paul’s School by 1596, indicates that football in England had, by this time, grown to “greatnes… [and was] much used in all places” He noted the positive educational value of football and was the first writer to refer to teams, positions, and a “training master” or coach. The game that Mulcaster describes is played between two small-sided teams under the auspices of a referee, or “judge of the parties” and offers clear evidence that the game being played was not the same as the mob football that people now think of as the main antecedent of the modern game.

These varying forms of football were played both in urban and rural areas. Most writers on the subject suggest that the game was played by the ‘lower orders’ of society, although Mulcaster’s work suggests that it was played in the Public Schools and the Stirling order of 1547 suggest that the Scottish Royal family had an interest in the game. There were certainly numerous attempts by the authorities to suppress it, which might suggest that it wasn’t a pastime that the aristocracy and ruling classes partook of.

However, in the early years of the Restoration, it is understood that Charles II and his court experimented with football. It would be nice to think that they did this as a reaction to the Puritan Commonwealth, under which a concerted effort was made to purge the country of football, and anything else fun.

Charles’ grandfather, King James I of England, and VI of Scotland, definitely thought that football was a good tool to annoy the Puritans with. In his Book of Sports, published in 1618, people are instructed to play at football every Sunday afternoon after worship. This seems to be an attempt to counteract the Puritans’ strict ideas about the keeping of the Sabbath.

We have good evidence for football being played in the 17th century at a site in Kirkcudbrightshire. Early forms of football appear to have been particularly popular in Scotland. Between 1627 and 1638, Reverend Samuel Rutherford, theologian, Presbyterian minister, and an extremely important figure in the history of the Church of Scotland, was the rector of Anwoth in Kirkcudbrightshire.

Letters that he wrote at this time indicate that he was unhappy that “on Sabbath afternoon the people used to play foot-ball” at Mossrobin Farm, close to Anwoth Kirk. To prevent his parishioners using this plot of land to play football, Rutherford had a line of stones placed across this playing area. Archaeological investigation of the area, instigated by the Scottish Football Museum, identified these stones and recovered dating evidence to prove that they had been placed there during the approximate period of Rutherford’s time in the parish.

The line of stones placed across the playing field in Anwoth to prevent the 17th century parishioners from playing football.

Photo Credit: The TimesIt appears that the Enclosure Acts of the 18th and 19th centuries might have limited the available spaces for people to play football as the common land was increasingly taken into private ownership. However, in his 1801 book ‘The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England’, the writer and folklorist Joseph Strutt described football as being played by two teams of ‘an equal number of competitors’ and on a playing area broadly the same size as that of a modern pitch.

Nonetheless, Enclosure, other government policies, and changes in society appear to have put pressure on football, limiting its practice. It survived better in some places than others, one of those being South Yorkshire in and around the villages of Penistone, Thurlstone, and Holmfirth. Matches were played according to the local, well-structured rules, with equal sides of limited numbers, between teams from the area were being organised well into the 1850s. It is clear that the local football tradition led to the prominence of the Hallam and Sheffield clubs that would later help to refine the Football Association rules.

While ‘folk football’, as it is often referred to, was under increasing pressure in the 18th and early to mid 19th century, other forms of football were well established, and part of the fabric of life, in the country’s elite public schools. The most famous of the football-playing public school is, of course, Rugby School. Although popular folklore insists that Rugby football was invented in 1823 when William Webb Ellis, during a game of football, caught the ball and ran with it, this is almost certainly a myth, with no first-hand evidence to support it and is dismissed by most historians.

The first set of written rules for Rugby football were compiled between the 25th and 28th August 1845 by three senior pupils at the school, William Delafield Arnold (the 17 year old son of the former headmaster), W. W. Shirley, who was just 16 at the time, and Frederick Hutchins. Although these rules have undergone several revisions since then, they are broadly recognisable in modern Rugby Union and Rugby League.

Many sources claim that the game of football played at Harrow School can be traced back for 200 years, but the oldest surviving rules for Harrow football date to 1858. An earlier date seems entirely reasonable though and it is believed that the game was played exclusively at Harrow School, between teams of boys currently at the school and between teams of current and former pupils, well before 1858. The game is played predominantly with the feet but the ball can be caught if it has not touched the ground since it was kicked and the kick was not a forward pass from a team mate.

The ball is of a shape that has been likened to that of a pork pie and measures approximately 18 inches in diameter and 12 inches in depth. Two even-numbered teams compete to propel the football into the other team’s goal, thereby scoring a ‘base’. The pitch is rectangular with the only markings consisting of the touchlines, goal lines, and a half-way line. The goals, or bases, consist of two upright posts placed 6 yards apart. The standard form of tackling, known as ‘boshing’, is essentially a shoulder barge which, to be performed legally, must come from either the side or the front and cannot include the use of elbows or raised arms.

A Harrow football. The vaguely pork pie shaped ball that is still used in the version of football played at Harrow School

Photo Credit: The Schoolwear SpecialistsAt Eton School, there are two distinct forms of football. The most famous of these is the Eton Wall Game, which is played on a strip of ground that is 110m long and 5m wide, immediately adjacent to a slightly curving brick wall. The wall against which the game is played was built in 1717 but precisely when the game was developed is unclear.

Writing in 1892, W. H. Tucker indicates that between 1811 and 1822, ‘football was almost confined to the wall game’, indicating that it was well-established by the early 19th century. The rules were first written down in 1849 and have been revised on 16 occasions since. The aim of the game is to move the ball to the opponents’ end of the playing area into an area called ‘the calx’. Within the calx, the attacking team can earn a ‘shy’, which is worth one point.

This requires a player to lift the ball against the wall with his foot and another player to touch it with his hand and shout “got it”. If the umpire gives this (by shouting “given”) the scoring team can attempt a goal which is worth a further 9 points. They do this by throwing the ball at a designated target; at one end, a garden door, at the other, a tree.

A player can also score a kicked goal, worth 5 points, if he kicks the ball at, and hits, one of the goals during the normal course of play. Despite this being the better known of the two forms of traditional Eton football, only a very small number of the boys in each year group take part in the game.

Eton school boys playing the Wall Game.

Photo Credit: ReutersThe lesser-known, but more widely played, code of football at Eton is the Eton Field Game. The first set of written rules date to 1847 but it was certainly played well before this date. It was one of the first varieties of football to be reported on in the English press, with the 29th November 1840 issue of Bell’s Life describing a game played on the 23rd of that month. The game is similar to modern Association Football inasmuch as the ball is round (one size smaller than a standard football), cannot be handled, and teams consist of 11 players.

Other rules, particularly the offside rules, are more akin to rugby, as are the positions of the players on the field of play. Scoring can be achieved by kicking the ball into the opponents’ goal, thus scoring a goal, which is worth three points. ‘Rouges’, the other method of scoring, are more complicated. The ball becomes ‘rougeable’ if it comes off a defender and crosses his own goal line or if a defender kicks it so that it rebounds off an attacker and over the goal line. Pupils at the school describe it as being similar to winning a corner in soccer. When a ball is rougeable, both teams race to reach it first.

If a defender reaches it, he can claim a single point or a ‘bully’, similar to a scrum, close to the opponents’ end of the pitch. If they drive the ball over the end of the pitch they score a ‘bully rouge’, worth 5 points. If an attacker reaches the ball first when it is rougeable, he scores a rouge, also worth five points. In both instances, the team scoring the rouge attempts to convert it. This requires the ball to be moved along a set of tramlines at the end of the pitch from the side towards the goal. The ball must be kept moving and remain within the tramlines. They can then attempt to score a goal or hit the ball off a defender to claim a rouge.

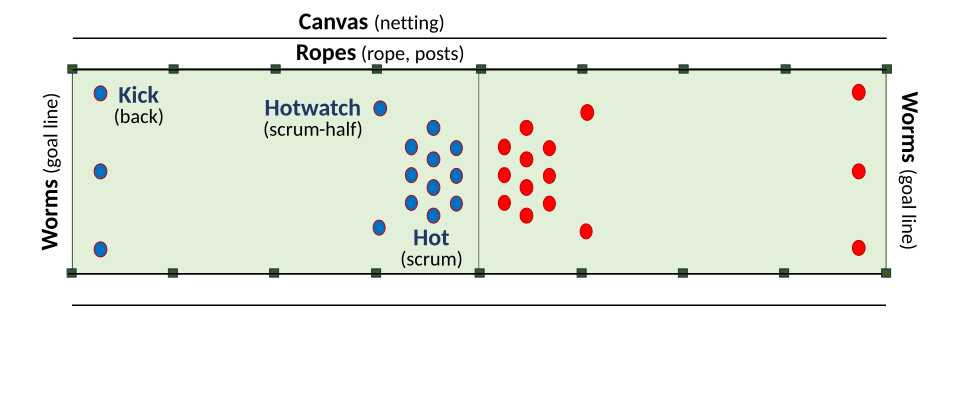

Perhaps the strangest of the public school games is that played at Winchester College. This game, sometimes referred to as “Winkies”, is played on a narrow pitch with dribbling banned, and shots on goal having to be below shoulder-height unless they are taken on the volley. Each team can only touch the ball once before the other team touches it and the aim is to get the ball, which is round, into the ‘worms’, the area at the opposing team’s end of the pitch.

There are similarities to Rugby; restarts occur through a scrum-like set piece called a ‘hot’, positions are similar with the ‘hotwatch’ performing a similar role to a scrum-half and ‘kicks’ operating a bit like full backs in Rugby Union. The offside rule is like a more extreme version of that used in Rugby. The ‘kicks’ are allowed to control the ball with their hands but the other players are banned from handling unless they catch the ball on the full toss. The Financial Times has suggested that a “Kasparov-like mind” is required to understand the complex and ever-changing rules.

The pitch or ‘canvas’ used in Winchester College Football and the positions taken up by the players.

Photo Credit: WikiWandBy the early 19th century, social factors, such as the enclosure acts, but also the Industrial Revolution, and the limits that this imposed on the free time of many working people, had caused football to become less widespread. This is possibly why the mob-football games played on holidays and feast days have endured in the public consciousness; these games were still played by the common man on the rare occasions that he had time off work.

The public schools were one of the places where the tradition of playing games of football were maintained, as the pupils here had sufficient free time and energy to partake in leisure activities. Initially, however, these games were scorned by those running the schools and even banned in some cases. This began to change as the concept of ‘Muscular Christianity’, the idea that physical strength and moral character were interconnected and so engaging in athletic activities could instil positive character traits, rose in popularity.

The games that were played at these schools were derivations of the folk games that were played in the countryside surrounding the schools or in the areas that the boys attending the school came from. Although these games were played in the English public schools, the character of the student body at these schools means that influences may have been drawn from across the British Isles. The public school games were, obviously, adapted over time, due to the various influences that boys coming from different parts of the country would bring with them and to suit the available spaces in which to play, leading to the codified versions at each school having a character of its own.

The existence of the Eton Wall Game and the fact that at Charterhouse and Westminster Schools football was originally played in the cloisters demonstrates that football was a game that could be adapted to suit the space available. This demonstrates a clear thread running from the folk games of the medieval period, through the public school games, to kids playing football in the street in the modern period, where the rules of the game are altered and refined to suit the circumstances of the locale where the game is taking place. This tradition of innovation can also be seen in the more formal modern variations of Association Football, such as 5-a-side, futsal, and even beach soccer.

By the late 1830s, public school football enthusiasts were gathering together at the nation’s great universities. They all wanted to continue playing the game they loved but encountered the obvious problem that they all played to different sets of rules. H. C. Malden, one of the early footballers at Cambridge, wrote that “every man played the rules he had been accustomed to at his public school” which led to confusion and arguments. In 1848, Malden and a group of other students, who had been at Eton, Rugby, Shrewsbury, Winchester, and Harrow, joined together to try to establish a common set of rules.

An initial meeting, which lasted almost eight hours, was followed by several more but eventually a set of rules was agreed upon. These were known as The Cambridge Rules, and they contained no place for the Eton ‘rouge’, catching was permitted but the ball had to be immediately kicked and could not be carried, a string was stretched between the goal posts which the ball had to pass under for a goal to be scored, and the offside rules followed the strict traditions of the public schools and effectively ruled out the possibility of passing in a forward direction.

Although a Cambridge Football Club was established which played to these rules, and they persisted, through various refinements and compromises, which allowed games to be played against teams from other institutions, into the early 1870s, these rules were never popular. The Public Schools showed no interest in adopting them. Rivalries between the different schools were strong and each thought that their version of the game was superior. In his excellent book Beastly Fury, Richard Sanders reports that the Eton men considered the game played at Rugby School to be ‘plebeian’ while the Rugby men thought that the Eton game was ‘effeminate’.

Another problem was that these games were deeply entrenched in their own customs, traditions, and history often with terminology unique to each school. The emotional ties to these games were so strong that no one could bring themselves to abandon their own game in favour of the hybrid, or ‘mongrel’, Cambridge Rules.

From the late 1850s, a number of football clubs began to appear in the London area, including the Forest club, which was established by the eldest sons of a wealthy shipbroker from Sunderland, Charles and John Alcock. The Forest club, who would later become the famous Wanderers club, played to a slightly modified version of the Cambridge Rules. Games between these clubs were genteel social occasions and, although many of the members were former public school boys, many, despite being middle class, were not from the same stratum of society and had learnt the game outside of the public schools.

The Forest Football Club XI of 1863.

Photo Credit: Historical Football KitsThe emergence of these clubs, and others, all playing different types of rules, led to renewed calls for a uniform and common set of laws. A fierce debate began in the sporting press and this precipitated, from the autumn of 1863, a series of meetings at the Freemason’s Tavern in central London. The public schools and the universities showed little interest and the attendees mainly consisted of representatives from clubs such as Forest, Barnes, Blackheath, Kensington School and others from the London area. It was at these meetings that the Football Association was formed. Arthur Pember of the Kilburn club was named president.

During the first couple of meetings there was acrimonious disagreement between those delegates that wanted ‘hacking’ (deliberately kicking the shins of an opponent) to be permitted and those who didn’t. The pro-‘hacking’ lobby held a small majority going into a meeting on the 24th November, which followed a trial match held four days earlier, at which it was intended that the new laws would be finalised. However, at this meeting, FA secretary Ebenezer Cobb Morley drew the delegates’ attention to the Cambridge Rules, which banned running with the ball in hand and ‘hacking’.

Discussion of this delayed the final decision on the laws to a further meeting, which was held on the 1st December. Many of the representatives who favoured ‘hacking’ and carrying the ball were absent from this meeting. As a result, these aspects of the game were banned in the final published 1863 version of the Football Association rules. Several clubs, such as Blackheath, who favoured a game more closely based on the Rugby rules, which allowed for ‘hacking’ and carrying, declined to join the Football Association. It is at this point that Rugby Football and Association Football diverged, leading to the creation of the two games we know today.

On 4th December 1870, Edwin Ash of Richmond Football Club and Benjamin Burns of Blackheath Football Club published a letter in The Times stating that “those who play the rugby-type game should meet to form a code of practice as various clubs play to rules which differ from others, which makes the game difficult to play”.

On 26th January 1871, a meeting attended by representatives from 21 clubs was held at the Pall Mall Restaurant on London’s Regent Street. There were two notable absentees; the representative from Wasps had been sent to the wrong venue and the representative from Ealing stopped in a pub and missed the event. As a result of this meeting, the Rugby Football Union was formed and the rules of the game were drawn up and formalised by three lawyers who were also alumni of Rugby School. These rules were approved in June 1871.

The 1863 Football Association laws did not lead to the immediate proliferation of clubs adopting Association Football as their preferred version of the game. In fact, uptake was slow and the rules were not popular. Rugby remained more popular amongst adult clubs, with the various public school games remaining popular amongst the relevant groups of schoolboys but never adopted by adult clubs to any extent.

Rugbeians remained resolute in their conviction that their game was superior. Snobbery played a part to some extent. The big noises in the Football Association, Cobb Morley, the Alcock brothers, and the FA’s first president, Arthur Pember, didn’t quite have the social standing of the ex-public schoolboy adherents to the Rugby game. Neither Cobb Morley or Pember had been to public school and the Alcocks’, despite having been educated at Harrow, were very much considered to be ‘trade’ due to their background and neither of them had attended Oxford or Cambridge.

C.W. Alcock, a leading light in the early FA and famed sportsman and journalist.

Photo Credit: The Streatham SocietyAnother problem, probably the main problem, was that the FA rule book, like the Cambridge rules, was a series of compromises. As a result, no one really recognised the game as their own and to many it must have felt very contrived. Particularly as there were many aspects that were very rugby-like which had been retained but others which had been jettisoned. The result sounds a bit like an unappetising, watered-down version of Rugby football. By 1867, the FA only had ten member clubs and several of these were lobbying to play under different rules. Only three clubs, No Names, Barnes, and Crystal Palace (a different organisation to the modern club), were consistently playing according to FA rules.

The three clubs playing the game according to the FA laws were all based in London. It was in Sheffield, however, that the key to turning Association Football into the game we know today was to be found. South Yorkshire and the villages surrounding Sheffield had remained a hotbed of football even during the period in the late 18th and early 19th centuries when the so-called ‘folk’ game was on the wane. In the late 1850s and 1860s the game in this area was beginning to flourish again. Many local cricket clubs started to adopt football as a game to be played out of season. This is how Sheffield Football Club (not to be confused with either United or Wednesday, two completely different clubs) came into being. In 1855, Sheffield Cricket Club started organising informal kick-abouts to retain fitness.

Subsequently, two of the members, Nathaniel Creswick, son of a silver plating manufacturer, and William Prest, whose family were wine merchants, formed a football club. Free from the public school influences, they developed their own set of rules, presumably based on the local ‘folk’ games, which were published in 1858. Many elements of this game were more akin to modern football than the original FA rules, although the goals were smaller and a form of the Eton rouge was retained for a while to help prevent 0-0 draws. In 1860, Sheffield’s great rivals Hallam Football Club were founded and the Sheffield rules that these clubs played began to increase in popularity and spread well beyond the South Yorkshire area. The Sheffield rules were the dominant version of the ‘kicking game’ for over a decade and the world’s first competitive football competition, the Youdan Cup, was played under the Sheffield rules, in 1867.

Sheffield FC had sent observers to the initial 1863 meeting at which the Football Association was formed. The club joined the new organisation despite having their own, widely used, set of rules. In November 1863, William Chesterman, club secretary, sent a copy of the Sheffield Rules to the FA and expressed the club’s opposition to hacking and running with the ball, which they considered to be “directly opposed to football”. With regard to hacking, Chesterman opined that “I cannot see any science in taking a run-kick at a player at the risk of laming him for life”. This intervention is considered to have contributed to the outlawing of these things at the FA’s meeting in December 1863. Following the final meeting at which the FA laws were ratified, very little seems to have happened, and Sheffield FC continued playing according to their own rules. In 1866, however, they suggested a match between themselves and one of the Football Association’s clubs.

This suggestion was misunderstood and Sheffield ended up playing a combined FA team, under FA rules, on the 31st March 1866. Several more games were played between clubs from the two different groups and this ushered in a period of dialogue between those playing the Sheffield Rules and the FA and its member clubs. The two sets of rules ran in parallel to one another, gradually adopting elements from each other, with significant changes to the FA rules occurring in 1866 and 1867 which moved Association Football definitively away from a Rugby-like game. An outright ban on handling was introduced to the FA rules in 1870, although this had to be clarified the following year as there was confusion over whether the goalkeeper was exempt or not. At the start of 1872, the FA adopted the corner kick and the free kick, by which time Sheffield had abandoned the rouge.

The two codes had almost converged, differing only on throw-ins (Sheffield used kick-ins) and the offside rule. The Sheffield club was so influential at this point, however, that it was given special dispensation to continue using its own rules. Eventually, it became clear that two, very similar, versions of the game, running in parallel with one another, was unsustainable. The Sheffield Football Association adopted the rules of the Football Association, following the adoption of a compromise throw-in law by the FA, in 1877. This is the point at which Association Football can be considered to have become the game we recognise today, although the rules have, of course, continued to be developed since that point.

One last significant convulsion in the birthing of the major UK forms of football occurred in 1895 with rugby’s “Great Schism”. Twenty-two rugby clubs in Cheshire, Lancashire, and Yorkshire split from the Rugby Football Union, mainly over the principle of ‘broken time payments’. This was effectively a response to the Victorian wrangling over professionalism. The ‘gentlemen’ players could afford to play for free but the working men who played these games, particular in the country’s industrial heartlands, couldn’t afford to miss a day’s wages to play sport and so needed to be compensated for their time.

Different sports responded in different ways. In cricket, teams fielded both ‘gentlemen’ and professionals. In Association Football, the often acrimonious debate eventually led to the acceptance of professionalism, although amateurs continued to play alongside the pros in to the 20th century. In rugby, the 22 rebel clubs formed the Northern Union, which eventually became the Rugby Football League and which developed slightly differing rules, leading to the existence of two distinct versions of Rugby Football.

Ireland’s sporting history and culture is as fascinating as it is unique. Hurling, one of the most recognisable Irish sports, is referred to in the Tain Bo Cuailgne, which is the tale of Ulster hero Cú Chullainn. Although the surviving version of this epic dates to the 12th century, it has been convincingly argued that it originated in the Iron Age (which in Ireland dates to between 500BC and AD400). There are other fascinating traditional Irish sports, one of my personal favourites being road bowls, a game in which competitors attempt to propel a metal ball along a predetermined course of country roads in as few throws as possible. Like the rest of the British Isles and north-western Europe, Ireland had a tradition of local folk football games during the medieval period, in addition to its more unique sports.

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) state, however, that references to football in Ireland are rare before the 1600s. Nonetheless, a game is recorded in County Meath in 1670. The poet Seamus Dall Mac Cuarta, who was blind, described a match played near Slane in the late 1600s and there are several further 17th and 18th century references to the game. In the early 18th century a six-a-side version of the game was played in Dublin and by the early 19th century games took place between county sides. During this period, a cross-country version of the game, similar to the games of mob football played elsewhere, known as caid, was popular in Kerry. A codified football game had emerged in east Munster by the 1840s. However, the arrival of Rugby and Association Football, which were popular with the upper classes, threatened the existence of native versions of football.

Ireland had a long tradition of athletic competitions and it was common for men to gather on Sunday afternoons and long summer evenings to compete in running and jumping events and particularly in weight-throwing. In 1857, Dublin University Football Club organised an event based on the formalised athletic meetings that had become popular in England over the previous decade or so. The idea took hold and the practice of holding formal athletic meetings spread across Ireland in the 1860s. These formal gatherings included many of the traditional rural events that formed part of their less formal predecessors.

However, over the next 20 years or so, a number of problems emerged. The different events consisted of numerous localised variants, several petty squabbles and personal disputes emerged and, because no one club or federation emerged to establish control over Irish athletics, there was no proper organisational structure. To fill this void, an increasing number of athletics clubs began to join the British Amateur Athletics Association, but this was to the detriment of the traditional Irish events, as the AAA were concerned more with their own events. To counter this problem, Michael Cusack, a man born into poverty in Clare, who had carved out a career as a teacher, and Maurice Davin, from a middle class Tipperary farming family, organised a meeting at Lizzie Hayes’ Hotel in Thurles, Tipperary at 3pm on 1st November 1884 to try and establish a new athletics association for Ireland. The result of this meeting was the Gaelic Athletics Association; the GAA.

Maurice Davin.

Photo Credit: Tipperary AthleticsAthletic events appear to have been the main focus of the GAA at the time of the organisation’s genesis; hurling and football were almost an afterthought. In their book The GAA, a People’s History, Mike Cronin, Mark Duncan, and Paul Rouse suggest that Cusack and Davin essentially had to invent Gaelic Football.

It seems, however, that there was a strong tradition of football for them to base this on. There are accounts of ‘Irish Football’ being played in South Australia in the 1840s and 50s, which suggests that there was a recognisable game played in Ireland, possibly the one that had emerged around this time in Munster, which was exported to Australia at this time.

The game that is considered to be the primary precursor to modern Gaelic Football is considered to have emerged about 1874 in South-West Ireland. Accounts of this game from Killarney suggest that it was very similar to Australian Rules Football, which had been codified in 1859. County Limerick was a stronghold of this game in the 1880s. The Commercials Club, founded by employees of Cannock’s Drapery Store in Limerick, was one of the first clubs to impose a clear set of rules and these were adopted, and adapted, by other clubs in the city.

These rules are believed to be the basis of the rules that were later adopted by the GAA. There appears to be some debate about how much influence these rules took from the Cambridge Rules of 1858, the Blackheath Football Club’s 1862 rules, and even the version of the FA rules from 1866. Whatever the extent of this influence, modern Gaelic Football is a unique and distinct version of the game, easily distinguished from the other modern codes.

Michael Cusack.

Photo Credit: GAAThere are some similarities between Gaelic Football and Australian Rules Football. Both games are dominated by kicking from the hand, both involve the use of hand passing, and the ball must be bounced by a player who is running in possession. The system of scoring is comparable and neither has an offside rule. There are, of course, also many differences and each is a distinct game but the similarities are sufficient that a hybrid game, known as International Rules Football, is played between representative teams from Australia’s AFL and the GAA. These similarities are unsurprising due to the historical connections between the two and the possibility that both drew quite heavily on the Cambridge Rules.

At one time, it was assumed that Australian Rules was based on Gaelic Football but the evidence doesn’t support this and it seems that the Australian game might have been more influential over Gaelic Football, the rules of which weren’t formalised until much later. Significant academic debate surrounding the nature of the relationship between the two games is ongoing.

Upper class European immigrants to Australia in the mid 19th century brought with them the codes of football that they had played at public school and university. It seems likely that some of the folk games that were played in the British Isles also made their way to the Antipodes, hence the references to ‘Irish Football’ being played in South Australia and New Zealand in the 1840s.

Accounts from Tasmania and Victoria suggest that the Rugby, Eton, and Harrow rules were those most widely played in these parts of Australia in the 1850s. In South Australia, it has been suggested that the Harrow rules had become the most widespread by the mid 1850s and many people assume that the rules of the Old Adelaide Football Club, which were published in 1860 but are now lost, were heavily based on the Harrow Game.

The rules of Australian Football were first drawn up in 1859 by members of the Melbourne Football Club. The impetus for drawing up the rules of Australian Rules Football came from Tom Willis, an Australian who had been educated at Rugby School. A year after his return to Australia from England, he wrote a letter to Bell’s Life in Australia suggesting that rather than allowing a “state of torpor to creep over them, and stifle their new supple limbs” cricketers should form a “foot-ball club, and form a committee of three of more to draw up a code of laws”.

The other members of the committee that Willis had suggested were Englishmen William Hammersley and J. B. Thompson, who had been students together at Trinity College, Cambridge, and Irish Australian Thomas H. Smith who had played a version of Rugby Football at Dublin University. They were familiar with English public school football and also with the terrain and conditions within Melbourne’s parks and open spaces. They developed a game that was influenced by these two factors. Similarities to the Cambridge Rules and the game played at Harrow School have been taken to suggest that these were the versions of the game that had most influence on the Australian Rules.

Australian Rules Football today. A mixture of kicking and handling, similar to the game outlined by the Cambridge Rules.

Photo Credit: ABC NewsIt has been theorised that Tom Willis may also have been influenced by games played by Indigenous Australian Peoples. Collectively, these games are known as Marn Grook, which comes from the Woiwurung language of the Kulin people and means “ball game”. These games were played at gatherings and celebrations and could sometimes involve more than 100 players and were played over very large areas. They involved punting and catching a stuffed ball and were subject to strict behavioural protocols.This theory is based on evidence that is possibly circumstantial and anecdotal. Willis was raised in Victoria’s Western District and was the only European child in the area.

He frequently played with the local Aboriginal children and became fluent in the languages of the Djab wurrung. It has been suggested that he learnt a game while playing with the local children that he later used in the development of Australian Rules Football. Like several other aspects of the early history of Australian Rules Football, there is fierce debate over the veracity of this theory and prominent rejections of it have caused some offence to Indigenous footballers. This is because the Tom Willis link has become culturally important to many Indigenous Australians from communities in which Australian Rules Football is very popular. Whether or not Tom Willis was influenced by Marn Grook, there are clear similarities between the games, making it understandable that the adoption of Australian Rules by communities with a tradition of playing such games seems a natural step.

So that’s pretty much all of the major modern codes of football covered, which leads us back to the game that my friends in Las Vegas assert is named for the size of the ball.

The more accurate story is that, in the early 19th century, colleges and universities in the United States began to adopt games similar to those played in the English public schools. Like in Britain, each school had its own particular set of rules. At Princeton, a game known as “Ballown” was played as early as 1820. A Harvard Tradition, known as Bloody Monday, began in 1827 and was essentially a mass ball game played between the freshman and sophomore classes. At Dartmouth College, a game called ‘Old Division Football’ was played from the 1830s, although the rules weren’t written down until 1871. It involved two teams of unlimited numbers and the rules, with the exceptions of the prohibition of kicking, tripping, striking, or holding another player, were largely bound up with the geography of the college grounds.

These games were very violent and a series of complaints and protests led to them being banned. However, football returned to college campuses in the 1860s with Yale, Princeton, Rutgers, and Brown adopting a ‘kicking’ game. Princeton used rules based on the Football Association’s 1866 set of laws. On November 6th 1869, a team from Rutgers University played a team from Princeton in a game using a round ball. They used a set of rules, suggested by Rutgers captain William J. Leggett and accepted by Princeton captain William Stryker Gunmere, based on the FA rules. Two teams of 25 faced each other with the winner being the first to score six goals; Rutgers won 6-4. A week later, a rematch was played at Princeton using Princeton’s own rules. Princeton won that game 8-0. In 1870, Columbia University joined the series and by 1872 several institutions, including Yale, were fielding ‘intercollegiate’ teams.

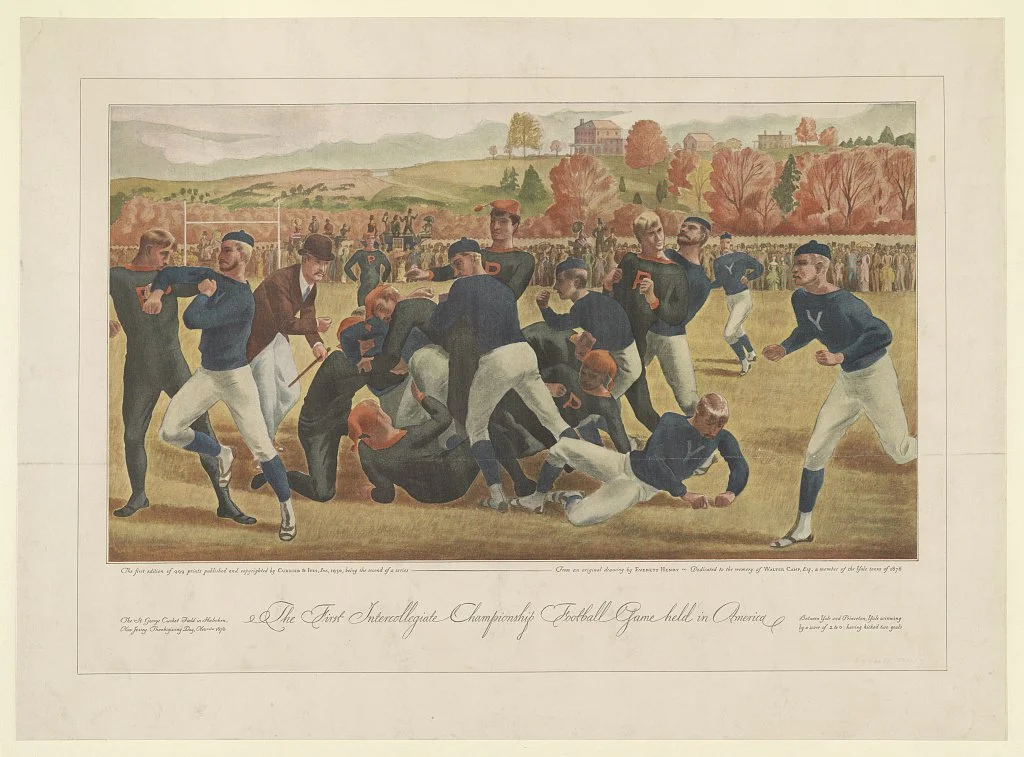

The first intercollegiate football game played in the USA. Princeton versus Yale, 6th November 1869.

Photo Credit: US Library of CongressBy 1873, attempts were being made to standardise the game. On 20th October of that year, representatives from Yale, Columbia, Princeton, and Rutgers met at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City to codify the first set of intercollegiate football rules. At this meeting, a list of rules more closely based on the Football Association rules than those of the recently founded Rugby Football Union were agreed upon. Harvard refused to attend this meeting, preferring to stick to their own code, known as the ‘Boston game’, even though this made it harder to schedule games against teams from other universities.

They did arrange a series of games in 1874 against McGill University from Montreal, where the rugby football rules were preferred. Harvard won the first game, played under the Boston rules, 3-0 but the second game, played under the rugby code, ended in a 0-0 draw. Harvard took a liking to rugby football and played a game against Tufts University using similar rules on 4th June 1875. They lost, but it didn’t dull their enthusiasm. They decided to challenge their closest rivals, Yale, to a game of football. The two sides agreed to play under a set of ‘concessionary’ rules, essentially a hybrid of the Association Football rules favoured by Yale and the Rugby rules favoured by Harvard. The game took place in mid November 1875 and Harvard won 4-0.

Amongst the spectators that day was one Walter Chauncey Camp. He enrolled at Yale the following year and played rugby football for the university at half back between 1876 and 1882. He rose to the position of captain and this led to positions on the various collegiate football rules committees that existed at this time. During most of Camp’s playing career, the rugby rules of the time required a tackled player, when the ball was ‘fairly held’, to put the ball down for a scrum. At the US College Football rules convention in 1880, Camp proposed replacing the scrum with the ‘line of scrimmage’, where the team with the ball started with uncontested possession. He also proposed limiting the number of players on each team to 11.

This was the catalyst for the evolution of American Football from the rugby-style game that was played in many of the American colleges at the time. Camp is also credited with introducing several of the other distinctive features of American Football, including the snap-back, the system of ‘downs’, and the points system. Camp was the first person to publish a book on American Football and pioneered the use of pictures and illustrations as coaching aids. He coached the Yale team from 1888 to 1892 and coached Stanford in 1892 and 1894-95. He served on the Intercollegiate Rules Committee for 48 years.

American Football is one of two versions of ‘gridiron’ football, so named because of the markings on the pitch (or ‘field’ to use the American term), arranged in a grid-like pattern. The other form is the less widely-known Canadian Football. The two games are very similar but Canadian Football is played on a wider, longer pitch, has teams of 12 players, rather than 11, has three ‘downs’ as opposed to four, and the goal posts are at the front of the end zone, on the goal line like rugby, rather than at the back of the end zone.

Like American Football, the game developed from football played under the rugby rules of the time, the first documented game of which was played on 9th November 1861 at University College, University of Toronto. The Burnside rules were a deliberate attempt to create a game that was distinguishable from the rugby game that was preferred in Canada at the time. They were first adopted in 1903 by the Ontario Rugby Football Union. This was considered to be a radical change and teams outside of the ORFU refused to adopt them until 1921. A concession did occur in 1906 though, when the system of downs was adopted.

Toronto Argonauts versus Winnipeg Blue Bombers in the 2024 Grey Cup Final, the Canadian Football version of the Superbowl.

Photo Credit: The Nelson StarThese rules were named after John Thrift Meldrum Burnside, captain of the University of Toronto football team, although he was not their originator. During World War I, the Reverend Robert Pearson drew up a set of rules for the Alberta Union which were heavily influenced by the Burnside Rules, which Pearson had known as a player. The other Western Canadian football unions agreed to use the Alberta Rules in 1920 and, in April 1921, the Canadian Rugby Union, which had been seeking to standardise its rules, proposed a set of rules that were very similar to the Alberta Union Rules and these were approved for the 1921 season.

Although based on the Rugby rules of the time, the game that these organisations in Canada and the USA adapted would have been referred to as ‘football’, as was usual in England at this time, where the game originated. Therefore, the games that they developed from the ‘football’ game that they acquired from the other side of the Atlantic continued to be called football.

Like the two North American codes, some of those early ‘folk football’ games were played predominantly with the hands. This has led to the suggestion that the term football refers to games that were played on foot, to distinguish them from sports and games played on horseback. However, games played with balls and sticks appear not to have been referred to in this way; hockey and hurling, both of which are played on foot, are not considered to be variations of football. Furthermore, in 1363, Edward III issued a proclamation banning “…handball, football, or hockey; coursing and cockfighting, or other such idle games” which suggests that distinctions were made between certain sports based on which parts of the anatomy could be used. It is perhaps more likely that the versions of ‘folk football’ which were handling-heavy had developed from games which originally incorporated more kicking.

No matter how much handling is involved in them, each of the major modern codes of football originated from a tradition of games, collectively known as ‘football’, which were played in the British Isles from at least the medieval period. These common roots are the reason that all of these games are known as ‘football’. The varying degrees to which the feet are used in each of the games does not make one game more legitimately ‘football’ than the others. And, as much as I love that bar in Vegas, the next time I’m in town, I’ll have to tell my friends there that the size of the ball has nothing to do with the game they love being called football.

Whether you are a fan of Association Football, Rugby Football, Gaelic Football, Australian Rules Football, or that thing where a load of Americans in crash helmets run into each other and fall over, these are the origins of the game you love.

This is the shared history of each of those games.

This is Football Heritage.