Words by Andrew Newton | Published 31.10.2025So there’s this bar in Las Vegas. You might remember, I’ve told you about it before. They play live music. Loud, live music. It’s in the open air and people wander in, have a drink, listen to the music, watch the bands, maybe have a dance. People watch the bartenders too; they’re flair bartenders, they juggle bottles and glasses and ice, they tell jokes and chat to the customers. If you’re lucky you might see one of the well-known bartenders walk round the circular central bar balancing a pyramid of bottles on his head. It’s a happy place and people are friendly. You walk in there and the chances are you’ll end up chatting to a stranger, maybe even making life-long friends.

I’ve chatted to people from all over the world in that bar, of all ages (over 21 of course, that’s the legal drinking age in the States) and from all walks of life. Quite often, the conversation turns to sport, which means that, at some point, football is mentioned. The game is a common cultural factor to which people from all corners of the globe can relate. Even if they’re not fans of the Association Football version of the game, they more often than not have an opinion on it, perhaps because their loyalties lie with one of the other codes of football that exist in the world today, maybe because they are devotees of another sport, or possibly because they dislike the game.

Whether you use spectatorship or participation as the metric, when people try to put together lists of the most popular sports in the world, soccer invariable comes out on top. Most estimates usually have at least one other version of football in the top ten, usually either rugby or American Football. Association Football is, therefore, almost a universal, something familiar to people everywhere and, thanks to globalisation, the internet, and the avaricious manner in which the football behemoth acquires audiences, the names of the biggest clubs and most popular players are known worldwide.

It is not just good marketing that has made soccer the global game. Association Football was immensely popular throughout the world before the relentless commercial onslaught of the Premier League, FIFA, and UEFA in the first couple of decades of the 21st century. It is most likely that football’s success is due to its simplicity. Unlike many other sports, the rules, or at least the most basic ones, are easy to learn and straightforward, making it easy to watch. The required equipment is minimal and a good approximation of that equipment can be easily cobbled together or substituted with more readily available items, making it easy to play.

There is something else about football though, in all of its modern forms, Association Football, Rugby Football, Australian rules, Gaelic Football, American Football, and Canadian Football, that makes it attractive. I believe that there is something almost elemental about them, something inherent within the Human race that draws us to playing games such as these. And the reason I say this is, despite all of the modern forms of football having evolved from medieval or earlier games played in the British Isles, similar games existed throughout the world in the distant, and not so distant, past.

As we started this in a bar in Las Vegas, let’s stay in North America where ball games were popular amongst the Native American peoples. Most of these were played with sticks, some being hockey-like in nature and others similar to lacrosse. These games include dehuntshigwa’es, baggataway and the Mohawk (or Kanien’kehá:ka) tewaarathon, a name which translates in to English as ‘little brother of war’. This name is an indicator of the social function of the game, which was sometimes used to settle disputes. It was a tough and sometimes brutal game but it was preferable to all-out war. Despite the dominance of stick games, the Algonquin and Powhatan played a game called pasuckuakohowog, the literal translation of which is ‘they gather to play ball with the foot’. The playing field for this was approximately half a mile wide with the goals set about 1 mile apart.

Beaches or clearings appear to have been used to play this game. No equipment, beyond a ball made of tightly bound animal skins or leather, was required and huge numbers of people, perhaps 500 to 1000, participated. Some accounts suggest that this was a bloodthirsty event with frequent injuries and that players wore war paint and other ornaments so that they would not be recognised afterwards and suffer reprisals. Alternative accounts suggest that the late medieval/early post-medieval Europeans that first encountered this game were surprised at how well organised and less dangerous it was than the football games that they were used to.

The size of the playing area and the numbers of people involved, as well as an apparent lack of extensive rules, mean that pasuckuakohowog has been likened to the games of mob football that existed in the British Isles. The earliest records of this game made by Europeans come from the first decades of the 17th century but it is reasonable to assume that it was played long before this.

A better known game can be found if we travel south to Mesoamerica, a pre-Columbian cultural region encompassing Guatemala, Belize, most of Mexico, western Honduras and El Salvador. A variety of ball games existed amongst Mesoamerican societies but the most famous is considered to have originated with the Olmec society, which flourished from around 1200BC before disappearing in the 4th century BC. The term ‘Olmec’, in the Nahuatl language of Central America, translates directly into English as ‘rubber people’. It is the Olmecs that are credited with being the first to extract latex from the Panama rubber tree and mixing it with juice from morning glory vines, which made the solidified latex less brittle.

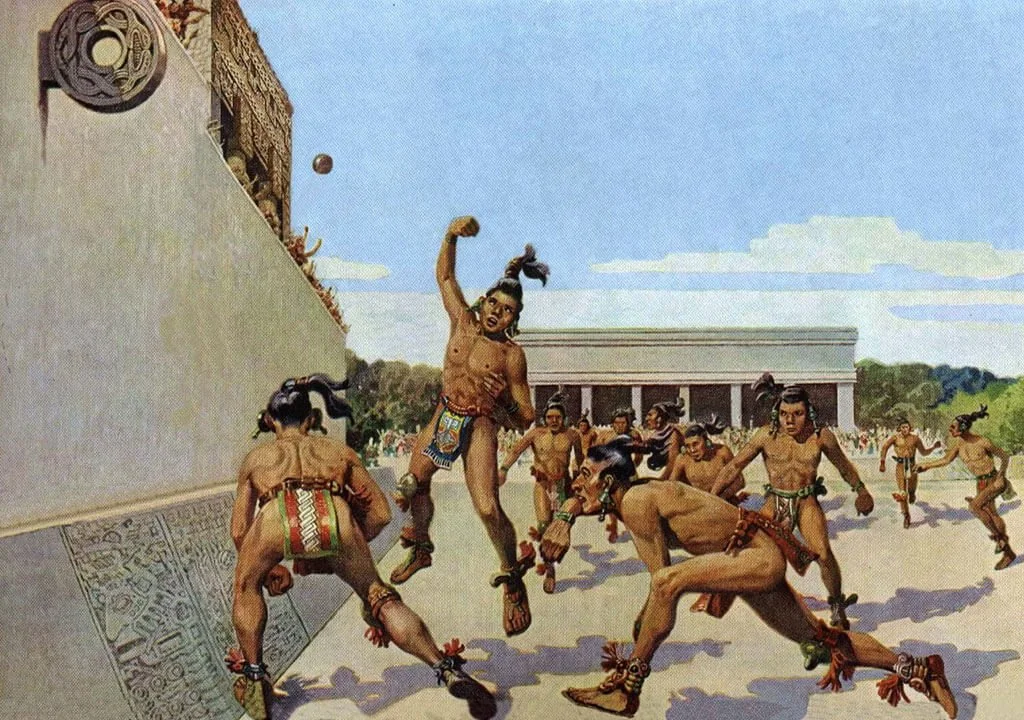

They therefore had the technology to produce the hard rubber ball used in the game that has become known as ‘the Mesoamerican ballgame’. This was a formal pan-Mesoamerican sport played in purpose-built courts. It is understood that a variety of other formal and informal ball games were played but this was the only one that appears to have required a formal court and appears to have been the most culturally important, appearing frequently in monumental art and other depictions.

A modern reconstruction of what the Mesoamerican ballgame may have looked like.

Photo Credit: Chichen ItzaThe game appears to have already had a long history before the Olmec civilisation reached its peak. A ballcourt in the Chiapas lowlands has been dated to 1650BC and, in 2020, archaeologists excavated a ballcourt dating to 1374BC at the site of Etlatongo in the Mixtec region of Oaxaca. This discovery has altered assumptions about the history of the game, suggesting that villages in these highland areas played an important role in the origins of the formal Mesoamerican ballgame, which became a crucial component of later societies in this part of the world.

The courts used for the ballgame were generally I-shaped in plan but vary in size from place to place. The exact rules remain unknown but it is possible that there are similarities with the game ulama which is considered to be a modern version played in some communities in the Mexican state of Sinaloa.

It has been possible, however, to infer some of the rules from pictorial representations on monuments, murals, temple walls, and household pottery, and from sculptures and the Popol Vuh, or Book of the Community, a document recounting the mythology and history of the K’iche’ people of Guatemala, one of the Maya peoples of eastern Central America. It appears that the ball was thrown onto the court by hand at the start of the game and from that moment on it could only be touched with the hips and thighs. The balls were made from solid rubber and ranged from 13 to 30cm in diameter and weighed between 0.5 and 7kg.

We don’t know how many players were involved, although the Popol Vuh implies that the game could be played one on one, in pairs, or in teams, and we don’t know the scoring system or how the winner was decided. Some sources suggest that the winner was the first to reach nine points although hitting the ball through one of the stone hoops positioned high on the walls of the ballcourt may have won the game instantly.

The game was played, not only by the Olmecs, but by subsequent civilisations such as the Maya, the Zapotecs, and the Aztecs and was still being played during the Spanish Conquest of the Aztec Empire in the early to mid 16th century AD. Over such a prolonged period, it is likely that the game evolved and developed, with the version that the Conquistadors encountered possibly being very different to the version played in the 14th century BC.

Religious and political meaning appears to have been applied to the game, with it often having a ceremonial function. It is bound up with the Mayan creation myth as described in the Popol Vuh. Part of this story describes the twins Hunahpu and Xblanque defeating the Death Lords of the Underworld at the ball game.

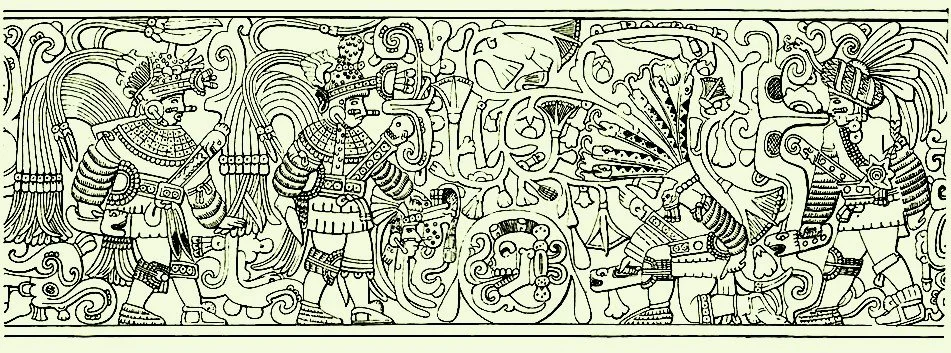

In their first game, the Lords tried to use a skull as a ball but the twins refused, then Hunahpu’s head was cut off and the Lords hung it over the ball court saying it would be used as the ball in the next match. Xbalanque fashioned a temporary head for his brother and persuaded a rabbit to impersonate the ball so that he could retrieve Hunahpu’s head and make him whole again. The links to this somewhat gruesome (and convoluted) story have led to suggestions that execution or human sacrifice was an element of the ritual surrounding the game, with some sources suggesting that the winning team were sacrificed and some that the losing team were sacrificed. This is reinforced by depictions of human sacrifice and decapitation on panels at some ballcourts, including that at Chichen Itza.

Some academics argue that this assumption is largely inaccurate and that it is more likely that these images relate to the creation myth rather being demonstrations of events occurring during the normal course of the game. However, there are some suggestions that the game could be used as a proxy for warfare, which in some instances may have led to executions. Defeating the Lords of the Underworld meant that the twins were able to free their father, the illustrious ballplayer Hun Hunahpu, allowing him to become the Maize God.

They themselves, after another series of complicated and gruesome events, ascended to become the sun and the moon, illuminating the world and making it possible for humans to be created. As a result of this part of the story, especially the bit about the Maize God, the game has been interpreted as being associated with fertility rituals and an interpretation of the movement of the sun across the sky.

Details from a panel at the Chichen Itza ballcourt depicting the decapitation of a ballgame player.

Photo Credit: Mexico LoreThe Aztecs approached the game in a slightly different way, although it continued to have political and symbolic significance. Aztec courts were often situated beside temples, suggesting a link between the two. Sixteenth century Spanish accounts indicate that kings and noblemen maintained professional teams and that these were sometimes used to settle political rivalries and disputes rather than resorting to armed combat. However, it is also suggested that the game attracted crowds and that the spectators gambled on the outcomes.

The long period over which the game was played in Central America, and the varying cultures with which it was associated, suggest that, as well its rules, its roles and meanings within those societies may have changed and developed quite widely. Most first-hand written accounts of the game come from the Spanish Conquistadors. Political motivations and negative attitudes towards the Mayan and Aztec societies that they were attempting to control may have led to descriptions of the game that were not favourable and not wholly accurate.

A very similar game, called Batey, was played by the Taino people of the Caribbean who, until the 15th century, were the principal inhabitants of The Bahamas, Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and the northern Lesser Antilles. They built their settlements around a central, usually rectangular, plaza surrounded by stones bearing carved symbols. The game took place within this plaza.

Batey was a game for two teams of between 10 and 30 players, using a ball made of rubber or a rubber-like resin. Normally, the players were men but occasionally there were mixed teams. The ball could only be struck using the shoulder, elbow, head, hips, buttocks, or knees but never the hands. When married women played, they did not use their hips or shoulders, but rather their knees. The ball had to be prevented from coming to a halt on the ground and had to remain within the Batey plaza. Points were earned when the ball failed to be returned, with the scoring system likened to that of modern day volleyball.

Batey appears to have been played for amusement, with players and chiefs making bets or wagers on the outcome of a game. However, it also appears to have had a function in settling disputes, it may have acted as some kind of judicial contest, and a prophetic function may also have been ascribed to it. As is the case with the Mesoamerican ballgame, most of the information about Batey comes from the accounts of European explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries which may not be entirely accurate. It is likely that Batey is related in some way to the Mesoamerican ballgame or, at least, to contemporary and similar games that were played in Central America during the same period.

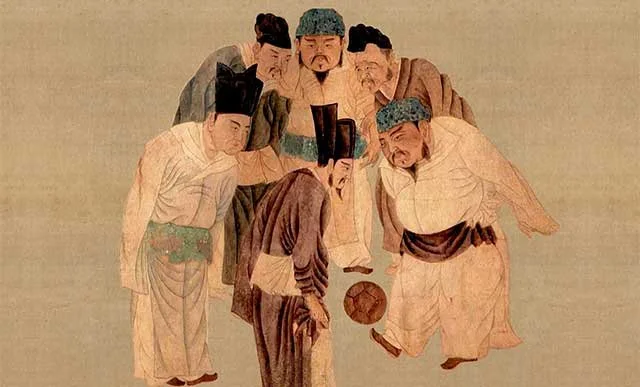

Several thousand miles away and several centuries later, on 15th July 2004 to be precise, Sepp Blatter announced that soccer originated in Zibo, Shangdong province, China. He was implying that football evolved from cuju, a game played in China since the Warring States Period of c.475-221BC. What motivated the then President of FIFA to make such a wildly historically incorrect statement is best left to speculation.

However, I am pleased to report that FIFA now, more accurately, refer to cuju as the earliest form of a ball-kicking game for which there is documentary evidence (which is in the form of a military manual from the Han dynasty) and state that “no case can be made that cuju influenced any of the modern ball games codified in the 19th century”. What the existence of cuju does prove is people’s innate love of playing games that involve kicking a ball.

Cuju translates as ‘kick-ball’ and the name serves as a catch-all for several different versions of a game in which a ball was kicked. The game appears to have been part of Chinese culture for around 2000 years, until its importance and popularity began to diminish during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), in part because it was banned as it was believed to be a distraction from other more important activities. During this prolonged period, it appears that different versions of cuju were developed and rose and fell in popularity.

A painting by the Yuan era artist Qian Xuau of the Emperor Taizu of Song playing cuju with Prime Minister Zhao Pu.

Photo Credit: China DailyOf the two best known versions, one was a competitive game in which two teams of between 12 and 16 players attempted to kick the ball through a goal consisting of a hoop or circular opening in the centre of a net-like target, without the use of their hands and without letting the ball touch the floor. Two different arrangements of these goals eventually emerged; they could be placed at either end of the playing area or a single goal could be placed at its centre. A second version, which became dominant during the Song dynasty, placed more importance on individual ball skills, with scoring goals becoming obsolete.

Points were awarded on the basis of skills, with poor touches, kicking the ball too far, not far enough, too low, or out of the playing area, or even turning at the wrong moment, leading to points being deducted. Aesthetics appear to have been an important consideration in the playing of cuju. Numerous manuals were written on the game and surviving examples of these demonstrate the various movements and body postures that were involved as well as 16 basic types of kick or touch that could be employed. This range of skills was known as xieshu. At its height, it appears to have been quite a demanding game that was highly complex and required great levels of skill and teamwork.

A modern reconstruction of cuju.

Photo Credit: China CultureCuju was played by both men and women, with members of both sexes able to attain professional status. It was also considered to be a suitable game for children. Cuju was played at important events, such as royal birthdays and such was its popularity and cultural significance that it became an important subject in poetry and art. The game was considered to be an important part of military training and was favoured by the highest ranking members of Chinese society; the first Han emperor, Gaozu (256-195BC), for example, constructed a large cuju court at his palace, and many in the Han ruling classes copied his example.

Nonetheless, cuju permeated all levels of society and, during the Tang dynasty, became part of the folk traditions of the Chinese people and was played during the Hanshi and Qingming festivals, important events in the Tang period calendar.

Several similar games exist in south-eastern Asian and, although this is denied in some quarters, it is likely that these games were influenced by cuju, radiating out along trade routes and as a result of imperial expansion. Amongst these games are Sepak takraw, which is played in Malaysia and Thailand (Sepak means kick in Malay and takraw is Thai for ball), and Sipa (meaning kick), a traditional sport of the Philippines. These games are very similar, played by small teams on a basketball or badminton-sized court, using a rattan ball. The games are similar to volleyball, or foot-volley, with the purpose being to propel the ball back and forth over a central net.

Another game played with a rattan ball is Chinlone, a traditional non-competitive game from Myanmar. This is typically played by groups of six people arranged in a circle with one standing at the centre of the circle. The object of the game is for the ball to be passed back and forth between the person at the centre and the people around its circumference, who are walking, without the use of their hands. Chinlone is very fast moving and the ball must be passed and received as creatively as possible. Technique is of the utmost importance.

It dates back approximately 1500 years and was first developed as a means of entertaining Burmese royalty. As such, it is more akin to a dance or performance than a sport and, indeed, it is heavily influenced by traditional Burmese martial arts and dances. Like the aesthetic versions of cuju, there are numerous recognised moves for passing the ball. In addition to the original form of Chinlone a single performance variant known as tapandaing has developed.

A craftsman making a rattan ball for use in chinlone.

Photo Credit: Sai Aung MainKemari is a Japanese game played with a stuffed deerskin ball, known as a ‘mari’, which weighs around 150g. The object of the game is to pass the ‘mari’ from player to player without it touching the ground; it has been likened to hacky-sack or a formalised game of ‘keepy-uppie’. The focus of the game is on technique, skill, and aesthetics, like the non-competitive version of cuju from which both chinlone and kemari are likely to have developed. It is generally accepted that kemari was introduced to Japan in the Asuka Period of the 6th to 8th centuries. The earliest record of the game comes from AD644, when it was recorded in the Nihon Shoki, an ancient chronicle of Japanese history. Its popularity increased during the Heian Period (AD794 to AD1185), during which it became compulsory for members of the kuge class, essentially the court nobles of Imperial Japan.

Its popularity extended to the samurai class from the late 12th century and the rules became standardised during the 13th century. By the Edo Period (1603-1867), kemari became popular amongst wealthy landowners and townspeople. However, after the Meiji Restoration (the overthrow of the military government of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the return of imperial rule to Japan), the popularity of kemari diminished. Following a donation from Emperor Meiji in 1903, a society to preserve this ancient game was established.

The playing area is marked by four trees, one placed at each corner, with each side of the square zone measuring 6-7m in length. It is traditional to use cherry, maple, willow, and pine as the trees marking the playing area. A game consists of six to eight people, with four primary players, known as mariashi, and up to four assistants. The game begins with a sort of warm up stage in which players kick the ball between themselves in order to get a feel for the ball. It appears that, due to their construction, the characteristics of each ‘mari’ could be quite variable.

The four mariashi take up positions in front of the trees in each corner of the pitch and the assistants position themselves outside of this. This warm up is followed by a phase in which the players demonstrate their individual skills to the spectators. The final stage, known as kazumari, emphasises teamwork in order to keep the ball airborne, and the number of kicks are counted. Having received the ball, a player can touch the ball as many times as he wants in order to make sure it is under control before passing it, in a high arcing lob, to the next player. The only part of the body that can be used to propel the ball is the foot, although other portions of the anatomy, with the exception of hands and arms, can be used to control the ball and direct it down the leg to the foot.

A depiction of a game of kemari during the festival Tanubata in 1799 by Ritō Akizato.

Photo Credit: Traditional SportsThe game is still played today, particular at Shinto temples, as part of specific events or celebrations. The game is highly ritualised and traditional kemari-specific clothing, based on an outfit which emerged for playing the game in the 13th or 14th centuries, is worn. The ball is blessed at a shrine before being taken to the mariniwa garden where the court is located, and prayers are said before the game begins.

The score, consisting of the number of kicks performed before the ball hits the floor, are counted by the designated official. Traditionally, he would count silently until 50 and then announce every 10 kicks. He could add an extra 10 when players performed a particularly skilful kick. Games would end when a pre-agreed number of kicks were completed, usually 120, 300, 360, 700, or 1000, all of which are numbers associated with astrology.

Kemari played in 2023 at Kyoto's Shimogamo shrine.

Photo Credit: The Japan NewsIn light of the popularity of soccer in Africa, and the continent’s rich football culture, it seems somewhat strange that there are very few ancient or traditional African games that can be considered to be comparable to any of the modern codes of football. The African continent is rich in traditional sports, which is unsurprising given its large size and the diverse and complex nature of its history. Many of these are martial arts or combative sports, including various types of wrestling, including Evala (Togo), Kokuule (Benin), and Laamb (Senegal). Dambe is a boxing-like sport from Nigeria, Niger, and Chad and there are various forms of stick fighting including Donga (Ethiopia), El Matrag (Algeria), Intonga (South Africa, Xhosa people), Istunka (Somalia), and Tahtib (Egypt).

There are some truly unique sports, such as Nzango, which is popular in the Republic of the Congo and DR Congo, and consists of a combination of dance and gymnastics in which participants compete one-on-one to mirror each other’s foot movements. There are a number of hockey-like games, such as Akseltag, which is played by nomadic tribes in Morocco’s M’Hamid El Ghizlane region. Players use sticks made of branches to propel a ball made of dromedary skin beyond the opposing team’s line. Genna, which is played in Ethiopa, is played with a brightly coloured ball made from tree roots and curved sticks made from eucalyptus, in which two teams of at least seven players compete on a playing field of 300m in length and 200m in width to hit the ball into the opposing team’s goal.

These games, like modern forms of hockey, have clear similarities to football inasmuch as the purpose is to direct the ball at (or beyond) a particular target. However, they lack the kicking or carrying of the ball which are common, to a greater or lesser extent, to all modern forms of football. In contrast, Dibeke, a game that is popular in South Africa, requires the kicking (and hand passing) of a ball, meaning that it has significant hallmarks of football, but the game play is more akin to cricket or baseball, so the aspect of two equal teams competing to move the ball to a certain location is missing.

It might be expected that football-like traditional games would be most likely to be found in the areas of North Africa that formed part of the Roman Empire, where such games are known to have existed. Ball games were popular in the Roman world, although not as spectator sports, and may have influenced certain medieval football-like games in other former parts of the Empire. Like several other elements of their society, the Romans are likely to have inherited their interest in ball games from the Ancient Greek world.

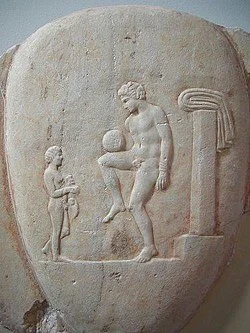

Ball games were quite widely played in Ancient Greece. They are even mentioned in Homer’s epic poem, the Odysssey. Most of what we know about these games comes from the writings of Julius Pollux, a Greek academic who lived in Naucratis in Egypt in the 2nd century AD. However, depictions of ball games have been identified in various contexts, including on Attic black- and red-figure pottery, sculpted on a funerary monument for an athlete who died prematurely, and on a grave stele discovered in Piraeus. This last image, of an athlete balancing a ball on his thigh, is reproduced on the Henri Delaunay European Championship Trophy.

None of these ball games, and indeed no competitive team sport of any kind, were considered to be serious athletic events suitable for incorporation in to the four great Panhellenic sporting events, the Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games. Instead, ball games appear to have been played for fun or as training methods for increasing fitness and boosting camaraderie between participants.

Boys about to play the Ethiopian game of genna.

Photo Credit: Traditional SportsA grave stele, discovered in Piraeus, depicting an Ancient Greek ballplayer.

Photo Credit: WikipediaNone of these ball games involved kicking the ball, mainly because the balls made in Ancient Greece were not suitable for kicking for sustained periods. Aporrhaxis was a game played with a small ball made of rolled up leather strips. Two players took it in turns to bounce the ball on the ground and in one version, at least, the player who managed to bounce the ball for the longest was the winner. Pollux’s description of the game suggests that it was a bit like dribbling the ball in basketball but it seems that the uneven nature of the ball and its lack of bounciness made this a more difficult skill than might be imagined. The game was considered to improve agility but, somewhat mind bogglingly, it seems that there were also some erotic and nuptial connotations involved.

Ourania, which means ‘heavenly’ was the name given to a game sometimes referred to as ‘sky ball’. The rules are not well known, but it involved one player bending over backwards and throwing the ball as high as possible while calling out the name of one of the other players, arranged in a circle around the thrower, who then had to catch the ball before it hit the ground. A similar game was ephedrismos, which means ‘carry on the back’, in which players formed pairs, with one carrying their partner on their back, while trying to catch the ball in similar circumstances to ourania.

There appears to have been another variant of this game in which a stone was set upright on the floor and players threw pebbles at it to knock it over. The winner would climb on the back of the other player, put their hands over the carrier’s eyes and the carrier then had to reach a target carrying his opponent. Ephedrismos was a game of agility and balance but, like other ancient games, had a symbolic element. The carried player was equated with Eros, the god of love, and the game was linked to marriage and fertility festivals.

Phaininda was a physical game in which the player holding the ball would pretend to throw it to one player, before unexpectedly throwing it towards another, according to the 4th century BC comic poet Antiphanes. It involved dodging and scrummaging. The origin of its name is unclear; Antiphanes suggests that it is named after the gymnastics trainer Phainestios, whereas Pollux suggests that it was invented by, and named after, one Phaenides or that it is derived from the Greek verb meaning to feint, deceive, or cheat.

Phaininda is generally considered to have been very similar to a better understood game called Episkyros. This was a game heavily based on teamwork, usually played by teams of 12 to 14 players, that was highly physical, even violent, and has been compared to rugby or American football. Unlike ourania and aporrhaxis, which were played by both sexes, it was typically played by men, although women did sometimes participate.

The playing area for Episkyros was marked with a central white line, called the ‘skuros’, which divided the two teams from one another, and another white line behind each team to mark the ends of the pitch. The idea was to get the ball over the opponents’ end line. The ball had to be passed between the players on each team and it seems that throwing the ball over the line was an acceptable method of scoring a point. The game required players to display agility, precision, endurance, and bravery.

The territorial element of the game, forcing the ball into an area or goal that the opponent is trying to defend, and which is absent from all of the other Ancient Greek ball games, is a key part of all modern games of football. It is perhaps for this reason that the 19th century originators of modern Association Football saw Episkyros as a forerunner of their own game. However, there is no clear evidence of a direct link between this ancient game and modern soccer and this connection is more likely to have been made due to the vogue for classical allusions amongst the university-educated sportsmen of Victorian and Edwardian England; see also the existence of the Corinthian Football Club and the Isthmian, Spartan, Nemean, Delphian, Hellenic, and Aetolian Football Leagues as well as the Mithras Cup, a floodlit competition for members of these leagues.

Ball games in the Roman world were seemingly regarded in a similar way to those of Ancient Greece; they were useful for training purposes and they were fun to play, but they weren’t serious athletic undertakings and they weren’t spectator sports. Boxing, wrestling, running, throwing events and spectacles such as chariot racing and gladiatorial combat filled these niches in the Roman world. Ball games were played by individuals from various social classes and they were played in the streets, at the baths, and in the fields. They were generally less structured than modern ball sports but were part of daily life.

Trigon (sometimes referred to as pila or trigonaria) was a popular Roman ball game and might have been adapted from a largely identical Greek game. It was a juggling game, probably involving three players (hence the name), passing a hard ball between them, catching with the left hand and throwing with the right. It has been suggested that the Romans played a game that involved striking a small ball, stuffed with feathers or wool, with a curved stick.

It has been suggested that this was a precursor to golf but this is probably inaccurate; hitting balls with a stick happens in lots of games and it would be grossly unfair to accuse the Romans of inflicting golf on the world. The terms folis, foliculus, paganica and arenata are also associated with ball games but it is unclear if these refer to specific games or types of ball. It is possible that they were interchangeable terms for different ball games.

The most significant Roman ball game, in terms of the history of football at least, was Harpastum. This is often considered to be a Romanised version of Episkyros and was played between two teams of approximately 12 players. The game was sometimes referred to as ‘the small ball game’ and it is generally suggested that the feather- or hair-stuffed ball was approximately the size, weight, and hardness of a softball.

The exact rules remain unknown but the game took place on a rectangular pitch, slightly smaller than a modern football pitch, with a baseline at either end. The objective was to move the ball beyond the opposing team’s baseline. Players could pass the ball between themselves and the opposition would attempt to gain possession by intercepting the ball in the air or by tacking players to the ground.

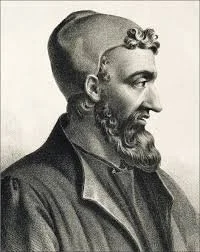

Literary sources indicate that Harpastum was a violent game and the name, which could be derived from a Greek word meaning ‘to seize’ or ‘to snatch’, reinforces this idea. Ball games were primarily played for recreation and enjoyment in the Roman world but they may also have served as a form of military training to promote physical fitness and agility. Certainly, letters written by the Greco-Roman physician Galen of Pergamon suggest that Harpastum was considered, by some at least, to be a suitable game for soldiers in camp to amuse themselves with while staying in shape.

Galen of Pergamon.

Photo Credit: The LancetAmongst the reasons that we know so little about Harpastum is the fact that it was largely a casual game, not played on a formalised basis, and so it was little documented and only really mentioned in passing in the available literary sources. Further hampering us is the fact that it required limited apparatus, just a ball, and unlike gladiatorial games and chariot racing, it didn’t take place in formal arenas, so there is little to no surviving material evidence of it. Nonetheless, Harpastum is significant in the history of football as it is often cited as inspiration for a medieval Italian game that is still played today.

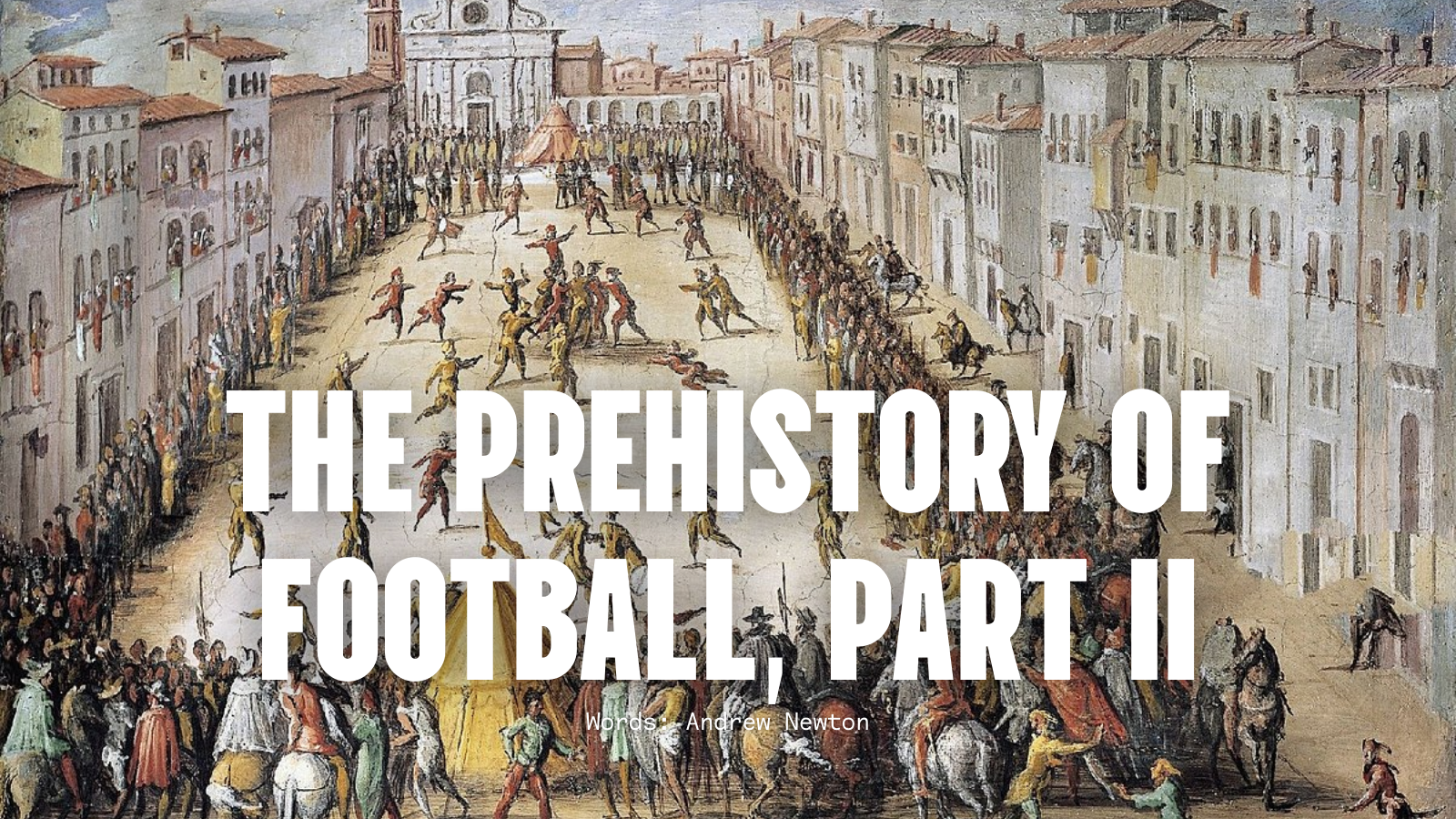

Calcio storico Fiorentino sometimes called calcio storico, or calcio in livrea is a broadly football-like game that, according to tradition, originated in Florence’s Piazza Santa Croce, where it is still played. Legend has it that it developed from informal, violent games used for training young soldiers and was popular between the 15th and 17th centuries. Calcio was played almost exclusively by the rich upper classes and aristocracy and was, at one time, widespread in Italy. Popes Clement VII, Leo XI, and Urban VIII reportedly played Calcio in the Vatican City.

One of the most famous games took place in February 1530 in Florence, while the city was under siege by the forces of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, as a colourful and noisy act of defiance to the besiegers. The official rules were published for the first time in 1580 by Count Giovanni de’ Bardi. De’ Bardi’s rules stated that participants must be ‘gentlemen from 18 years of age to 45, beautiful and vigorous, of gallant bearing, and of good report’. Members of Florence’s ruling Medici family, including Piero II, son of Lorenzo il Magnifico, played, as did Vincenzo Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantova.

Interest in Calcio started to wane in the 17th century and the last official match on record was played in Piazza Santa Croce during January 1739. The game endured in the collective folk memory and it continued to be played informally in the streets. However, in 1909, during a wave of nationalist sentiment in Italy, the national football federation, the Federazione Italiana del Football changed its name to Federazione Italiana Gioco del Calcio, effectively adopting an Italianised name for Association Football and making certain implications about the origins of soccer.

Thirteen years after this name change, growing nationalism resulted in the assumption of power by Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Party. In 1930, the local Fascist Party leader in Florence, Alessandro Pavolini, who had led a squad of blackshirts during the 1922 march on Rome, resurrected Calcio Fiorentino as an expression of national culture. The first game was set for 4th May 1930, marking 400 years since The Siege of Florence, following which Alessandro de Medici was installed as leader. Pavolini’s reinvigorated game followed de’ Bardi’s rules from 1580.

Action from a modern game of Calcio Storico.

Photo Credit: National GeographicThose rules dictate that the game is played by two teams of 27 players, on a sand-covered playing surface measuring 100m in length and 50m in width. A white line divides the playing area into two equal halves and a goal net runs the width of each end. Matches last 50 minutes.

The 27 players consist of four datori indietro (effectively goalkeepers), three datori innanzi (like fullbacks), five sconciatori (halfbacks), and 15 innanzi (forwards). Substitutions are not allowed, even for injured players. The captain and team standard bearer sit in a tent at the centre of the goal net, they do not take an active part in the game, but can organise their teams and act as a sort of match official, mainly to keep players calm and prevent fights. Players are not identified by numbers but each by a different symbol, including a lion, a pear, a key, a star, and a dragon.

The aim of the game is to get the ball into the opponents’ goal, thereby scoring a caccia, using any means necessary. Players can use hands and feet and games generally start with the 15 forwards on each team engaging in a period of fighting and wrestling, intended to tire out their opponents or to pin down as many players as possible. Punching, elbowing, and head butting are all permitted but only one player can attack an opponent at any one time.

Kicks to the head are banned and, since 2008, men over 40 and convicted criminals are barred from playing. Once there are enough incapacitated players, the remaining members of the team can swoop in to retrieve the ball and attempt to score. The teams change ends every time a caccia is scored but precision is important as every time the ball is thrown or kicked above the goal, half a caccia is awarded to the defending team. At the end of the allotted time, the team that has scored the most cacce is the winner.

Today, three matches are played each year to a backdrop of elaborate pageantry. Players and officials don 16th dress, hence the name calcio in livrea- calcio in costume. Two semi-finals are played prior to the feast of San Giovanni, patron saint of Florence, on the 24th June when the final is held, preceded by a renaissance-themed parade through the town, incorporating drummers, flag bearers, heralds, and armed guards. The annual competition is played between teams representing each of the four districts of old Florence.

These teams are the Azzurri (blues) of Santa Croce, the Bianchi (whites) of Santo Spirito, the Rossi (reds) of Santa Maria Novella, and the Verdi (greens) of San Giovanni. The draw for the semi-finals is made on Easter Sunday, during the ‘Scoppio del Carro’ when four marble eggs, coloured to represent each team, are placed in a velvet pouch. The first two eggs withdrawn from the pouch represent the teams that will compete in the first semi-final while the remaining two represent the teams that will play in the second semi-final.

Azzurri vs Rossi.

Photo Credit: Lonely PlanetThe adoption of the word calcio (meaning ‘the kick’) as the Italian word for Association Football was a deliberate attempt by Italian nationalists to claim the modern game as their own. Guidebooks available in Florence during the Fascist period made explicit links between calcio storico and soccer. Even the great Italian football journalist, Gianni Brera, claimed that the English were not the originators of the game and had merely ‘reinvented’ it. Despite some resistance, the word calcio became the accepted norm.

Calcio storico certainly has some significant football-like elements and could be regarded as being similar to some of the folk-football games from the British Isles that are identifiable as precursors to the modern codes of football. This, however, does not mean that the Italians can claim to be the originators of those modern games. Calcio is considered to be descended from Harpastum and there are similarities between Harpastum and Episkyros and the East Anglian game of ‘Camp ball’ and the Cornish game of ‘hurling to goals’, particularly in terms of the size and solidity of the ball.

However, it cannot be said with the same level of confidence that these medieval games descended from those played in Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, at least partly because of the social changes that occurred following the Roman withdrawal from Britain. It is even harder to identify a continuous line between the modern codes of football and the ancient games of Central America and south-east Asia. There is, however, one ancient game that appears to have had a significant influence on one of the modern versions of football.

Marn Grook is the collective name for traditional Indigenous Australian football-like games that have been played for at least 1000 years. The most common versions of the game involve the punting and catching of a stuffed ball made from possum skin. These games were played at gatherings and celebrations and are subject to strict protocols associated with kinship groups as well players being matched for size and gender. Sometimes games could involve more than 100 players. There are no distinct rules or scoring system and no real team objective, although preventing the ball from hitting the ground appears to have been a common aim. Instead players who displayed outstanding individual skill, including accurate and high kicking and leaping higher than others to catch the ball, were praised.

It has been suggested that Tom Willis, one of the three men who drew up the rules of Australian Rules Football in 1859, was heavily influenced by Marn Grook having observed games during his childhood. This link between the games is of huge cultural significance to Indigenous Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, amongst whom Australian Rules is extremely popular. Fierce academic debate about whether or not Willis was influenced by Marn Grook has raged for some time in Australia and refutations of this link have caused great offence.

There do appear to be similarities between the two games, including the large amount of time the ball spends in the air and the practice of ‘high marking’, or leaping to catch the ball at the highest point possible, which was one of the indicators of a skilled Marn Grook player. Although the AFL maintain that Marn Grook did have a role play to in the development of ‘Aussie Rules’, there doesn’t appear to be any clear resolution to the debate.

It mainly revolves around whether or not Marn Grook was played in the area in which Willis lived during his childhood and a lack of documentary evidence specifically stating that there was a link. Whatever the truth, this seems like a pretty futile argument. If Willis wasn’t influenced by Marn Grook, the fact that Indigenous Australians see similarities between ‘Aussie Rules’ and this traditional game, to the extent that they consider it to be culturally significant, surely adds something for everyone, making ‘Aussie Rules’ a game that all communities in Australia can come together to enjoy.

A modern day Marn Grook ball in the collections of Museums Victoria.

Photo Credit: Museums VictoriaSome of these traditional and ancient games are characterised by skill in kicking and controlling a ball. Others are characterised by the territorial aspects of defending and attacking a particular area. Occasionally both elements are present, as they are, to a greater or lesser extent, in all of the modern forms of football. These fundamental aspects of these games are very appealing. Kicking, throwing, and catching a ball is fun and mastery of such skills impresses other people. The territorial element appeals to the inherent competitive nature of human beings and has been likened to battle; some psychologists have suggested that there are sexual connotations to this element of football. As the great satirical fantasy novelist Terry Pratchett wrote “the thing about football- the important thing about football- is that it is not just about football”.

Despite people occasionally making claims to the contrary, usually for their own gain, it is not possible to state with any certainty that there is a direct connection between any of these ancient games and the games that led to the development of the modern forms of football. What is more likely is that ball games like this are bit like pyramids; a solution to a particular problem, or in this case a good idea for a form of entertainment, that was struck upon several times over, independently and in different locations, at slightly differing points in history. In short, those fundamental aspects of modern football games are simple concepts that contribute to making good games and naturally occur in the minds of human beings.

All of the modern codes of football combine these simple concepts, repackaged into formats that are both fun to play and entertaining to watch. Rugby is sometimes described as the epitome of sport, due to its blend of teamwork, physicality, and strategic complexity. The Association game, however, is undeniably the world’s most popular sport. It combines the twin fundamental aspects of mastery over the ball with the battle-like territorial struggle of defence and attack in an almost equal balance all the while being, at the same time, both frustratingly difficult and beautifully simple. If rugby is the epitome of sport, soccer is surely the perfect balance of art and struggle; the ultimate distillation of all of these ancient games.

It appears that football, or games like it, are a natural part of being human.

Mankind was always destined to kick a ball.