Words by Dave Proudlove | Published 20.08.2025When I was a young boy, my dad once said to me – with a straight face – that he’d sung on a single that made the top 40, a claim that left me both bemused and confused at the same time. Dad hadn’t got a musical bone in his body, and beyond his impersonations of Mick Jagger – which were a regular occurrence at parties and family gatherings, think a slightly more sober Oliver Reed on Aspel and you’ll get the picture – Dad and musical aspirations were not likely bedfellows. But Dad was pretty straight, and he pulled out a 7-inch single and told me to listen. The single in question was ‘We’ll Be With You’ by the Potters, which wasn’t a band but a group of Stoke City fans – and Dad was one of them – who gathered in the old Stoke City Supporters Club to record the song written by local girl Jackie Trent.

She co-wrote a number of hits for Petula Clark with Tony Hatch, who she eventually married, but is perhaps most famous for writing the theme tune to Australian soap opera Neighbours. ‘We’ll Be With You’ was recorded ahead of Stoke’s League Cup final triumph over Chelsea in 1972, and made number 34 in the charts, and the bet365 Stadium regularly echoes with the sound of what is the club’s ‘official’ anthem; we won’t mention ‘Delilah’…

‘We’ll Be With You’ by The Potters.

Photo Credit: 45cat.comFollowing World War II, football and pop music became arguably the most potent expressions of working class identity, growing out of a sense of hope, optimism and spirit of renewal in a country weary from six years of conflict. Indeed, they have gone on to become two of the most influential global cultural phenomena of the last century. Each captivates millions – if not billions – across continents, generations, and social classes, and their intersection on our terraces and stands is not just coincidental; it's a powerful reflection of how entertainment, identity, nationalism, and globalism collide and coalesce in contemporary society. From anthems sung in stadiums to footballers becoming muses or collaborators for pop stars, the relationship between football and pop music is rich, dynamic, and emblematic of wider societal trends.

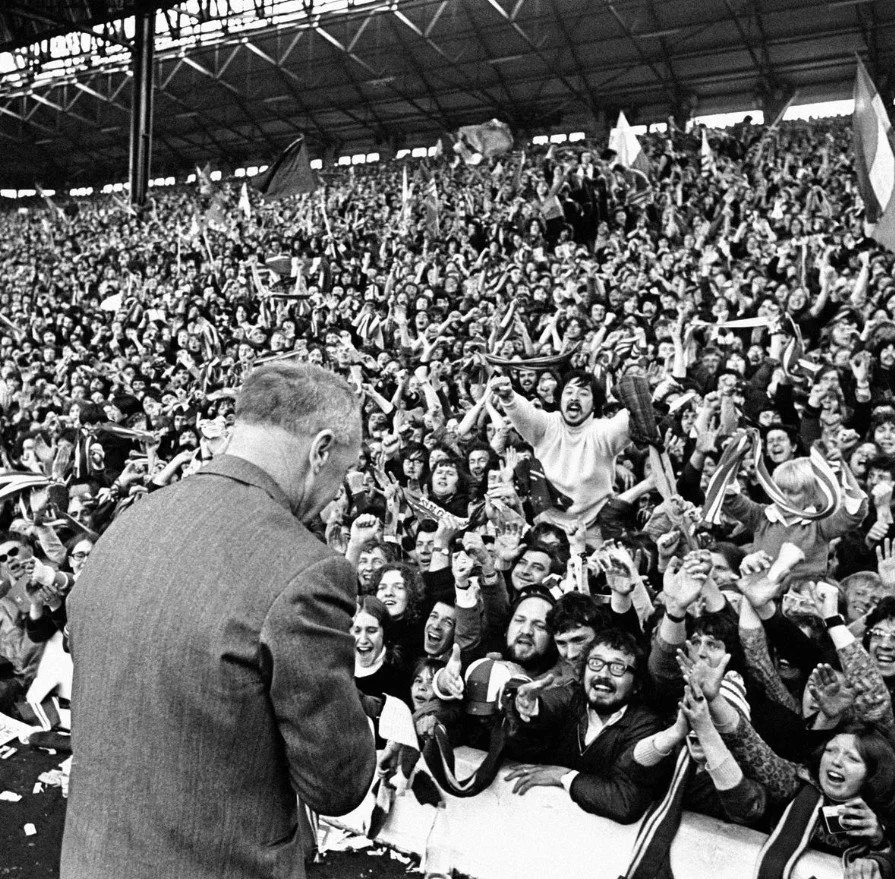

In post-war Britain, football clubs were largely local institutions tied to factories and working class communities, while the music scene – especially rock ‘n’ roll in the 1950s and 60s – reflected youthful rebellion and authenticity. Cities like Liverpool, Manchester, and London became both footballing and musical powerhouses, and the two collided on the terraces in often joyous spontaneity. Witness the Kop at Anfield swaying and belting out the early Beatles single ‘She Loves You’, and their adoption of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ made famous by locals Gerry and the Pacemakers.

The Kop singing during the 70’s.

Photo Credit: The Liverpool EchoAs Liverpool’s great rivals Manchester United rebuilt following the Munich air disaster, a world class talent that hailed from the streets of Belfast emerged as the club’s great young hope. George Best turned on the style on the pitch, lived the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle off it, and became known as the ‘fifth Beatle’ thanks to his Beatle-esque looks and charm.

As the 1960s became the 1970s, the football single started to become a thing. The England squad that flew out to Mexico to defend their title in the 1970 World Cup finals hit number one on the Top 40 ahead of the tournament with ‘Back Home’, beginning a trend for World Cup singles. However, England’s miserable international form following their quarter-final exit in Mexico meant that another World Cup single wasn’t released until 1982, when the squad reached number two with ‘This Time (We’ll Get It Right)’, the first football-related song that I remember as a young boy.

The England World Cup Squad had a minor hit ahead of the 1982 World Cup Finals.

Photo Credit: Dempster’s DiscsBy the 1970s and 80s, British football was grappling with hooliganism, yet it still formed a critical part of local identity. Simultaneously, pop music diversified with punk, ska, and new wave—genres that reflected the disillusionment of the working classes. Bands like the Clash and the Jam channelled anti-establishment sentiments also echoed in football terraces. Football chants even began to resemble punk songs: raw, loud, and communal, and often laced with aggression (“you’re gonna get your fucking heads kicked in”), while some punk bands turned out songs that could almost have come from the terraces; witness Sham 69’s ‘Hurry Up Harry’ and its “we’re going down the pub” refrain, while the Undertones’ top 10 single ‘My Perfect Cousin’ referenced Subbuteo, as did its glorious sleeve.

By the mid-1980s, English football was suffering with an image problem with a reputation for thuggery, while games were played out in crumbling and dangerous grounds. English clubs were banned from European competitions following the Heysel Stadium disaster in 1985, but England still qualified for the 1986 World Cup finals in Mexico. And the squad were dragged into the recording studio to record the by then obligatory World Cup single. ‘We’ve Got the Whole World at Our Feet’ proved to one of the less memorable World Cup efforts and stalled – ironically – at number 66, perhaps reflecting the standing of English football among the wider public at the time. But 12 months later, two of England’s World Cup squad were to have an improbable hit single after an impromptu karaoke performance at a sponsor’s event secured them a record deal.

Glenn Hoddle and Chris Waddle were Tottenham Hotspur team mates, and key members of a side that reached the 1987 FA Cup final playing some excellent football under David Pleat, and their karaoke session led friends from the music industry to pair them up with songwriter and producer Bob Puzey, who’d worked with the likes of the Nolan Sisters and the Dooleys. Puzey wrote a fairly forgettable synth-pop tune for Hoddle and Waddle, but when it was released a month before Tottenham’s FA Cup final clash with Coventry City – under the name Glenn & Chris – it became a surprise top 20 hit. ‘Diamond Lights’ reached number 12, leading to a Top of the Pops appearance that became legendary but not in a good way, with one journalist savaging the duo’s “truly awful dad dancing and shocking lyrics”, while another lamented the song and their TV appearance as "a timeless classic for all the wrong reasons... you get the feeling that Waddle was rightly embarrassed to be there while Hoddle genuinely felt he was at the start of something big." Waddle later said that appearing on Top of the Tops was the most nerve-racking thing he’d ever done, but that presumably didn’t include the penalty shootout in the 1990 World Cup semi-final.

Glenn Hoddle and Chris Waddle performing ‘Diamond Lights’ on Top of the Pops.

Photo Credit: BBCBut if ‘Diamond Lights’ was the sublime of 1980s football-related singles, what followed 12 months later would definitely fall into the ridiculous category. Not to be outdone by Hoddle and Waddle, Liverpool found their way into the top 40 the following year with the seriously mad ‘Anfield Rap (Red Machine in Full Effect)’, co-written by midfielder Craig Johnston, Paul Gainford, rapper Derek B, and Mary Byker from Gaye Bykers on Acid. The single was released towards the end of Liverpool’s storming league campaign and ahead of their shock FA Cup final defeat to Wimbledon, peaking at number three in the charts.

The summer of 1988 saw a miserable England performance at the European Championship finals in West Germany where they finished bottom of their group, losing all three of their games. This disappointing showing saw manager Bobby Robson savaged in the tabloid press, but he led them to the 1990 World Cup finals in Italy after England came through their qualifying group unbeaten. And that set the squad up for the recording of another World Cup single, and this one was a genuine game changer.

New Order were formed from the ashes of Joy Division following the suicide of frontman Ian Curtis, and were – at the time – Manchester’s biggest band, and Factory Records’ premier act. They probably seemed like the unlikeliest band to come up with a World Cup song. But the FA’s press officer at the time, David Bloomfield, had been a big fan of Joy Division and reached out to the head of Factory Records Tony Wilson, suggesting that New Order penned England’s World Cup single. Wilson responded in the positive, and after a bit of sport with the agent acting on behalf of the England squad, New Order got to work in crafting the World Cup single alongside comedian Keith Allen.

The song was developed during an interesting period for English music and culture. A generation pissed off with the direction the country had taken under the Thatcher government tuned into the sounds of the Acid House scene, grooving at unlicenced raves often held in derelict factories and warehouses, rendered useless by the economic policies of Thatcher and her colleagues. This youth culture explosion was fuelled by the use of MDMA, or ecstasy in popular parlance, and the blend of music and a drug that had euphoric effects led it to be fondly known as the Second Summer of Love.

Following Ian Curtis’ death and the demise of Joy Division, the remaining members were joined by drummer Stephen Morris’ partner Gillian Gilbert, and the band – by now known as New Order – were heavily influenced by the electronic music coming out of Detroit, Chicago, and New York, and they were soon producing musical landmarks such as ‘Blue Monday’, and albums such as Power, Corruption and Lies. It was no surprise that Manchester was at the heart of the Acid House scene, and New Order were almost godfathers to the movement having already embraced electronic sounds.

This was the context in which they wrote England’s 1990 World Cup single, and their first effort blatantly riffed off it, and the band presented a song titled ‘E for England’ that included the lines “E is for England, England starts with E/We’ll all be smiling when we’re in Italy.” The song was quickly parked; even the stale suits at the FA realised that it was a song that sounded like a celebration of ecstasy.

The majority of England’s squad were unwilling to get involved in recording the single, with many having a negative view of World Cup songs. But when the squad assembled ahead of a pre-World Cup friendly with Brazil at Wembley in March 1990, the FA insisted that the squad met up with the band at the Sol Mill recording studio in Berkshire. Despite the FA’s request, only six players turned up, John Barnes, Peter Beardsley, Paul Gascoigne, Steve McMahon, Chris Waddle, and Des Walker. The only restriction that the FA placed on the band and the players was an insistence that hooliganism should not be referenced in any way.

The players recorded their vocals with the band over a backing track that bore resemblance to an instrumental that Morris and Gilbert had produced for the BBC, before John Barnes performed his now iconic rap. Barnes was selected ahead of the others who were rejected either due to their accents, or their inability to keep the required rhythm. The song also included a number of samples including the famous “they think it’s all over” line from Kenneth Wolstenholme’s 1966 World Cup final commentary. The single was produced by Stephen Hague who’d worked with the band previously on songs such as ‘True Faith’, and was released on 21 May 1990. It was to be New Order’s last ever release on Factory Records and became their only number one single, and in the words of New Order frontman Bernard Sumner, “was probably the last straw for Joy Division fans.”

England went on to reach the semi-finals in Italy, their best performance in years, while the tournament went on to play a key role in the reshaping of English football, which was still dealing with the fallout from the Hillsborough Disaster the previous year. Italy’s futuristic new stadiums heavily influenced the new generation of English stadia that rose across the country following the publication of the Taylor Report, and on the pitch, the team’s performance and the emergence of Paul Gascoigne as a genuine world-class talent provided optimism that the nation’s footballing fortunes were about to change for the better.

When I think about the 1990 World Cup finals, a few things immediately spring to mind. Hot summer sun. Pavarotti’s version of ‘Nessun Dorma.’ Isotonic Lucozade Sport. Cameroon shocking Argentina. Gazza’s tears. And ‘World in Motion’, the greatest football single of all time.

New Order, Keith Allen, and John Barnes – World in Motion.

Photo Credit: Getty ImagesThe early 1990s saw a period of change and an ushering in of a new era for English football, but not before England had floundered in a second European Championship finals, this time in Sweden under Bobby Robson’s replacement Graham Taylor, where they again exited at the group stage without winning a match. But the real big noise was the launch of the Premier League. Sky TV’s ‘whole new ball game’ was beamed into homes around the world, and it had a soundtrack: Simple Minds’ ‘Alive and Kicking’.

A big part of Sky TV’s marketing of the Premier League was – and still is – the atmosphere generated inside our grounds. The noise and passion was seen as vitally important to the Premier League ‘product’, and central to that were the songs and chants, the sounds of the crowd, and many of them originated from pop songs. ‘Blue Moon’ was adopted by Manchester City supporters. Under George Graham, Arsenal had become adept at grinding out 1-0 wins, and so the Gunners faithful responded with the ironic ‘1-0 to the Arsenal’ chant to the tune of ‘Go West’ by the Village People, which was also adopted by fans of Manchester United as they paid tribute to Eric Cantona with their ‘Ooh ah Eric Cantona’ chant.

With the advent of the Premier League, interest in the domestic game increased hugely while the promise of better times for the national team faded. Paul Gascoigne had left Tottenham for Italy and a £5.5m transfer to Lazio, but not before suffering a serious injury in his final game for Spurs, the 1991 FA Cup final. The injury put him out of action for a lengthy period of time; he missed the entire 1991/92 season. He returned the following season but couldn’t help England qualify for the 1994 World Cup finals in the USA. A miserable qualification campaign saw them finish third in their group behind Norway and the Netherlands. Graham Taylor resigned to be replaced by Terry Venables who had two years of friendlies ahead of him as England qualified automatically for the 1996 European Championship finals as hosts.

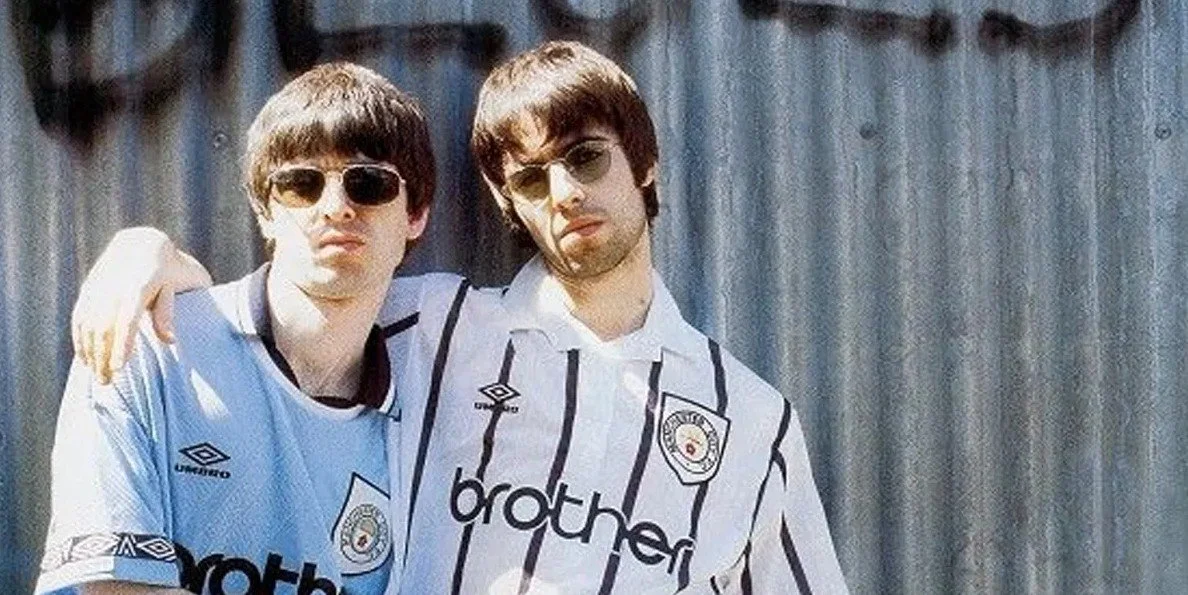

The 1996 European Championship finals came with a country on the brink of change. John Major’s Tory government was on its last legs, out of steam, out of ideas, and was consistently enveloped in scandal. Labour, led by Tony Blair, were riding high in the polls and were odds-on to win the 1997 General Election. At the same time, the British music scene was undergoing a resurgence. Bands like Blur, Oasis, and Pulp were dominating the charts and the airwaves – the so-called Britpop scene – and despite being governed by a party that was falling apart, there was an air of optimism about the country. Indeed, it can be argued that music and football were critical components of Labour’s 1997 General Election landslide.

And riding that wave of optimism were Oasis, led by the feuding Gallagher brothers. Oasis emerged in 1994 pledging to become ‘bigger than the Beatles’, releasing their first album Definitely Maybe, which became the biggest selling debut album of all-time in the UK. Their second album – (What’s the Story?) Morning Glory – followed in 1995 and was even bigger, and as the 1995/96 football season was coming to a close, the band headlined two shows at Maine Road, the home of Manchester City, the club that Liam and Noel Gallagher supported.

The feuding Gallagher Brothers, Manchester City lovers.

Photo Credit: Kevin CumminsAhead of the 1996 European Championship finals, the FA approached Ian Broudie of the Lightning Seeds and asked him to write a song for the European Championship. Being a football fan, Broudie grasped the opportunity with both hands, and wrote a melody that he thought would make a good football chant. He declined the offer of involving the England squad, and instead approached comedians David Baddiel and Frank Skinner, hosts of the popular football comedy show, Fantasy Football League. Broudie said that he didn’t want the song to be ‘nationalistic’, instead wanting it to be about being a football fan, “which, for 90% of the time, is losing.”

‘Three Lions’ eventually developed a life of its own, the “its coming home” refrain echoing around football grounds and pubs all over the country as the single predictably topped the charts and became universally popular – it even made number 49 in the German charts – with Melody Maker describing it as the “best football single of all-time.”

Baddiel, Skinner, the Lightning Seeds and Three Lions.

Photo Credit: AlamyBy this point, it had become ‘OK’ to profess your love of football again. Prime Minister Tony Blair claimed to be a Newcastle United fan and was filmed playing head tennis with Magpies boss Kevin Keegan, while rock star after rock star were making clear who they pledged their footballing allegiances to. However, while the new kids on the block had been a little shy when it came to football, some of rock’s veterans had never had a problem with singing the praises of their team. Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant is a Wolves fanatic and has been a regular at Molineux for decades, and is now a club president, while the ridiculous Rod Stewart often talks about his faux Celtic heritage and is frequently spotted at Parkhead.

Led Zeppelin frontman Robert Plant lines up with Wolves players ahead of the League Cup Final, 1980.

Photo Credit: AlamyAside from various reprises of ‘Three Lions’, and the occasional dreadful effort such as Ant & Dec’s ‘We’re on the Ball’, the football song seems to have died a death, though with 2026 bringing up 60 years since England’s World Cup victory, you can imagine Ian Broudie dusting off ‘Three Lions’ once more, assuming England qualify for next year’s finals of course.

But the relationship between music and football endures. You cannot think about Geordie rocker Sam Fender without thinking about Newcastle United, while Ed Sheeran has always professed his love for Ipswich Town. And Oasis are back with a huge tour following their reunion, with various Manchester City players and manager Pep Guardiola in tow.

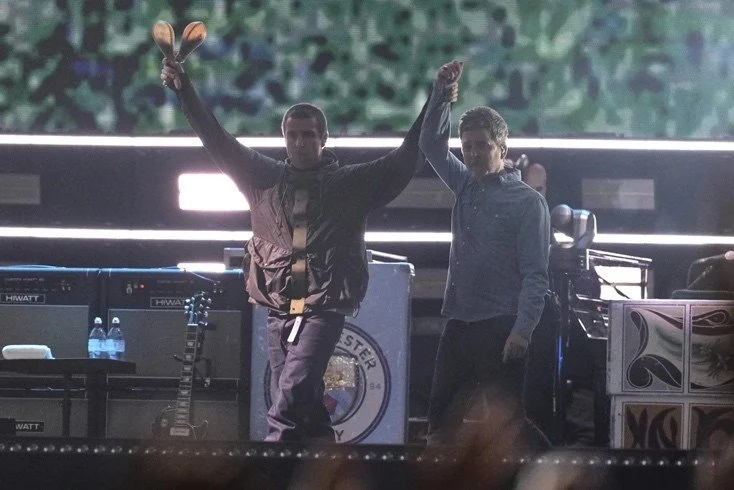

Oasis are back – and Manchester City are with them.

Photo Credit: Scott GarfittFootball and pop music, though different in form, serve remarkably similar purposes. They bring people together. They stir emotions, tell stories, and reflect societal values. They are both languages of identity: personal, communal, and national. From stadium chants to World Cup anthems, from footballer-musicians to pop stars in club kits, the connection is enduring and evolving. In a fragmented world, these two art forms remain among the last truly global experiences.

And as long as there are fans in stadiums, artists on stage, and goals to be celebrated, the symphony between football and pop music will continue to echo – loudly and joyously – throughout the land.