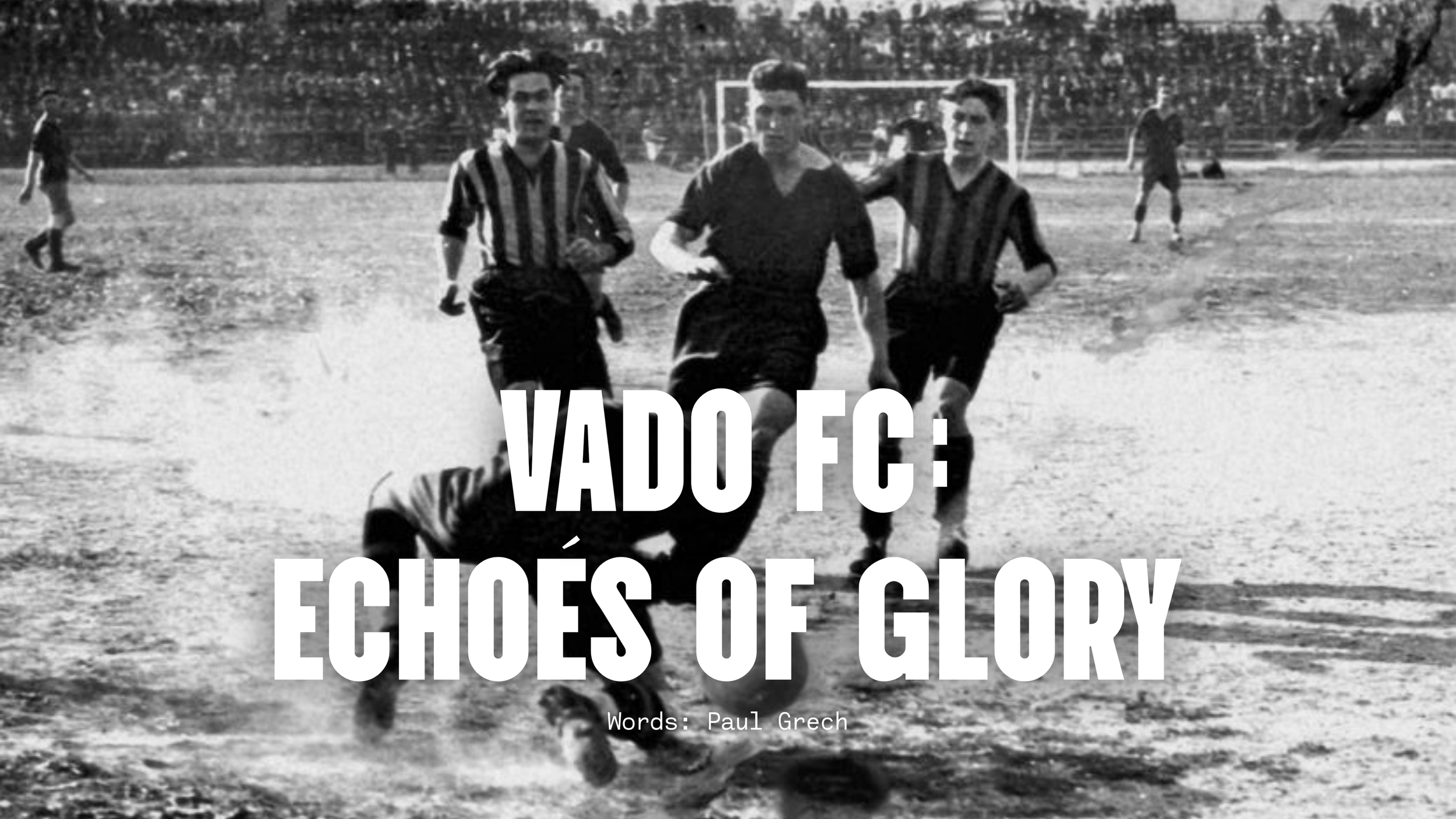

Words by Paul Grech | Published 15.08.2025Perhaps it was the poor weather, typical of a wintry late January day, but just around 300 die-hards made it to the Stadio Ferruccio Chittolina. Most had braved the cold and wet weather in the hope of seeing home side, Vado FC 1913, beat relegation threatened US Albenga. They made as much noise as they could despite knowing that this was mostly in vain; their chants quickly fading in the fractionally filled stadium that could house up to 2,000 people.

No matter how hard they tried, their efforts had little effect on the home players who could only manage a 1-1 draw. It was a humdrum affair that only those hardy souls with a direct interest in either of the two teams could ever possibly be interested in, just as they do every weekend when their sides go out to play in the Serie D, the fourth tier of Italian football.

Yet on that pitch was a side that could boast of a notable achievement; a national title that will forever etch its name alongside those of the greats of the Italian game.

For those looking closely, the only hint that there was anything special about either of those clubs lied in the crest of the home team, one that featured a large white star on a background that is split equally between blue and red. The colours themselves are an homage to Vado's home region of Liguria that is blessed with beautiful seas (hence the blue) and plenty of sun (the red).

Neither of these elements are particularly remarkable or even original; the first great side to emerge in the region and indeed all of Italy – Genoa Cricket and Football Club – bears those same colours. This is not coincidental either: Vado were formed by Genoa fans.

The importance here isn’t the colours but the image, that of the star. Stars in Italian football are a serious matter. When Juventus were stripped of two league titles due to Calciopoli back in 2006, many fans despaired because this set them back from gaining a third star that had appeared so close. At the highest level, a star symbolises the victory of ten Scudetti and with 29 titles, Juventus were on the verge of adding a third, (something that they have since done and celebrate at every occasion). Crucially, their bitter rivals from Milan were both stuck on one.

Similarly, when the badge of the national team was re-designed in 2017, the then president of the Italian association, Giorgio Tavecchio, boasted "we have made the four stars that represent our four World Cup triumphs more visible because they represent the pride of all our nation".

So, Vado FC’s inclusion of a star on their stem is significant, but of what? They never played in the Serie A. A handful of seasons in the second tier during the early days of the game is the highest that they ever managed to climb, so there was no prospect of it signalling ten national titles. In fact, they’ve barely won ten honours at any level and, regardless, no one would dare boast of such minor triumphs in such public fashion without risking the scorn of everyone else.

Yet Vado’s star is there by right.

A further – crucial - hint over what it represents comes from the final element of their crest: three concentric circles bearing the green, white and red colours of the Italian flag. That is the symbol traditionally borne by the holders of the Coppa Italia the season following their triumph, a reminder of their win that clubs wear on their shirts for the full season following that success.

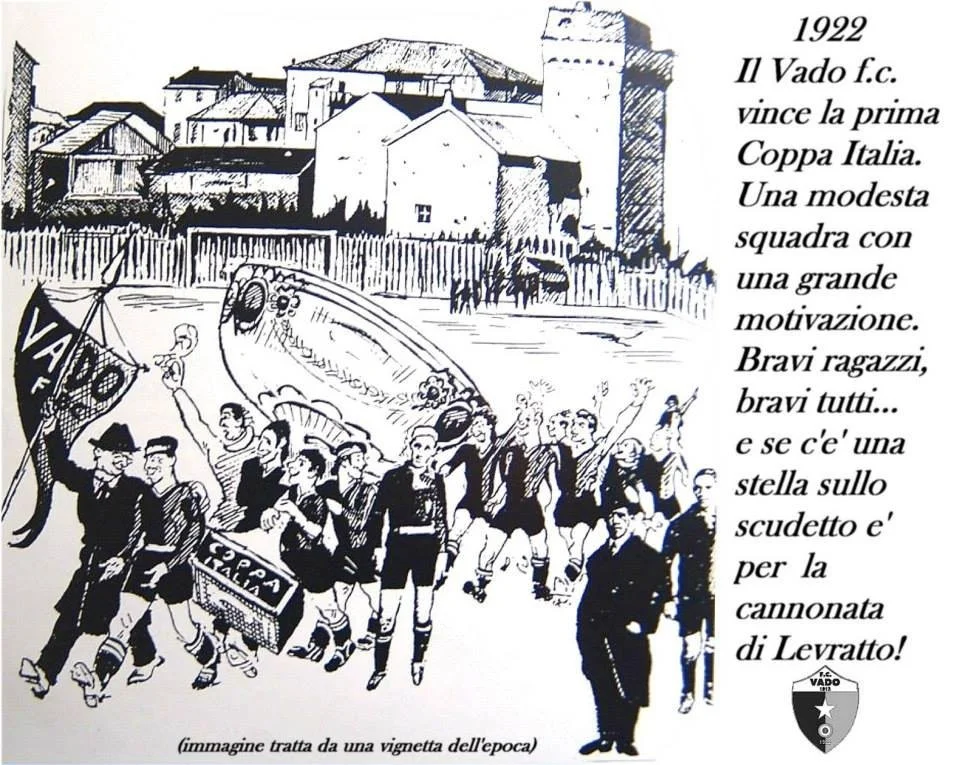

And that is what Vado’s star symbolises. Because way back in 1922, at the birth of the competition, they delivered what remains the biggest surprise in Coppa Italia history by taking the cup home.

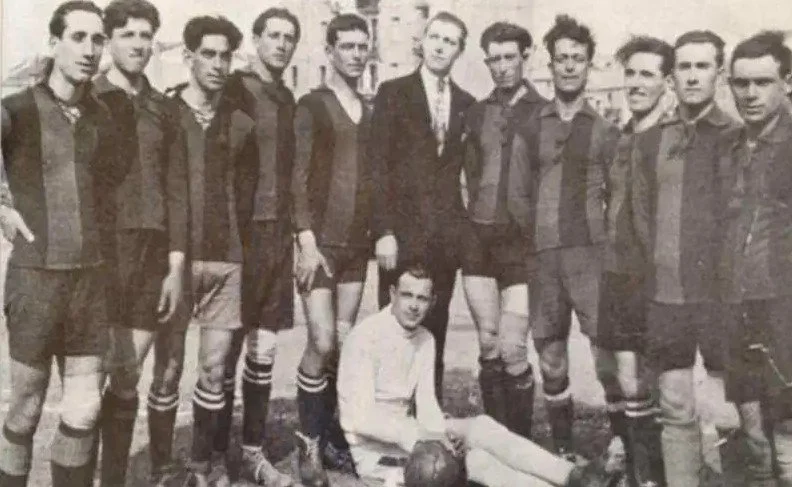

An early squad Vado FC squad photo.

Photo Credit: The Gentleman UltraItaly had played a significant role in the First World War, after it switched sides from the Central Powers to support the Allies in fighting against Austria-Hungary on the Italian front whilst also contributing to other campaigns. It was a fruitful move and at the end of the conflict Italian borders were pushed outward to include Trentino, South Tyrol and Trieste, a reward for their support.

Yet these spoils of victory did not meet what had been agreed in the Treaty of London back in 1915 which had convinced Italy to switch, much less justify the cost of around a million Italian lives. Shouldering a feeling of betrayal, matters were made worse for Italians leaders when they returned home to a country facing food shortages, inflation and debt.

Inevitably this led to social unrest. Inspired by the wave of Marxism sweeping across Europe, Italy entered a grim period now referred to as the biennio rosso (the two red years) marked by mass strikes, worker demonstrations and land and factory occupations, with attempts at self-management by revolutionary socialists and anarchists.

Sadly, this achieved little, and unfortunately facilitated the rise of the fascist countermovement led by Benito Mussolini and his blackshirt militia. In October of 1922, Mussolini and his fascist supporters marched on Rome and effectively seized power by force, after which they managed to quell the protests in a matter of months through a mixture of violence, intimidation, and propaganda.

Italian football was going through an equally turbulent time. The game’s popularity had led to a rapid growth of clubs but not necessarily in quality. Those hailing from the north – which tended to host the richer and better organised sides – began pushing for a league with a better structure than the system in place at the time which featured eighty-eight teams divided into regional groups.

The demands of the few failed to convince the majority and when raised with FIGC, the national federation, were voted down. Incensed, the most prominent twenty-four teams broke away, setting up the Conferderazione Calcistica Italiana (the Italian Football Confederation) and, in turn, the Northern League as a rival to the existing league structure.

Bereft of its top clubs – Juventus, Torino, Milan, Inter, Genoa, Bologna, Lazio and Napoli all formed part of the rebel group – but unwilling to bow to their demands the FIGC found itself in a bind. Necessity being the mother of invention, they came up with the idea of a brand-new competition that could spark enthusiasm despite the absence of the most prominent clubs.

Thus came into existence the Coppa Italia. Heavily inspired by the FA Cup which had historically allowed all teams, regardless of size, the opportunity of winning a national title, the FIGC made the new tournament open to everyone. All that the entrants had to do was prove that they had a fenced playing field, willingness to cover the travelling expenses of their rivals and ability to pay the FIGC a 100 Lire participation fee.

Thirty-five clubs took up the challenge with most being unheralded smaller sides that have been lost to time. This included teams like Fiorente Genova, Torinese, Virtus Bologna and Juventus Italia Milano. Some, however, held a more glorious future as with the case of Libertas Firenze who eventually became Fiorentina.

One of the few historic team photos of Vado FC which exist.

Photo Credit: Storie de CalcioVado FC were also at the starting line. In the nineteen-twenties the town was one of the great Italian industrial centres with foundries, chemical and petrochemical plants and ship demolition yards. Even Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company – an early rival to Thomas Edison’s General Electric – had a base manufacturing electric locomotive there.

It was in this hive of manufacturing activity that a group of friends came up with the idea of setting up a club of their own. That idea eventually became reality in November 1913 where, wearing the blue and red of their beloved Genoa, they played friendly games in a parcel of land sandwiched between a paint factory and the train station. Enthusiasm around the club grew enough to enable the construction of a new purpose-built stadium whilst the team’s games took a more structured feel when they enrolled in the FIGC’s newly set-up regional leagues towards the end of the same decade.

For all of this, Vado was not a club with huge ambitions. They wanted to offer a healthy outlet for the factory workers, most of whom had little access to any other form of entertainment. It was arguably that ambition which convinced them that an opportunity to take part in a national competition was too good to miss.

The new tournament envisaged three preliminary rounds before reaching the quarter-final stage. Luck favoured Vado by giving them home advantage in their first three games where they enjoyed a dramatic 4-3 win against Fiorente Genova before registering fairly comfortable wins against Molassano (5-1) and Juventus Italia Milano (2-0).

These enabled qualification to the quarter-final where, for the first time, they had to play away from home. A trip to Tuscany to face Pro Livorno proved to be a challenge but eventually they won 1-0 with the winner scored fifteen minutes from time.

A week later they welcomed Libertas Firenze. It was another tough game befitting a semi-final. Both teams nullified each other and neither could find an edge, sending the game into extra-time. This too failed to provide any goals until, with the teams destined for a replay, Vado finally found a breakthrough in the dying instances, scoring the goal that opened their path to the final.

It was the kind of result that the FIGC must have loved for it totally fulfilled their original ambition of emulating their English counterpart. “Italian football has nothing to envy its English sibling,” claimed the Gazzetta dello Sport on the morrow of Vado’s victory.

“A club from the Promozione league finds itself a finalist in the Coppa Italia.”

The Udinese side of 1922.

Photo Credit: Storie de CalcioVado’s run to the final owed a lot to the squad's unity and determination, a fitting tribute to a town built on hard work. There was, however, flair running through the side. None more so than when Virgilio Felice Levratto took hold of the ball.

Still seventeen when Vado kicked off their Coppa Italia commitments, Levratto had been a regular for quite some time and scored four of their goals en-route to the final, his side’s top scorer. In fact, he’d signed his first contract with the club four years earlier when barely in his teens, testament to his precocious talent.

The second of four brothers, his mother had long gotten used to him coming back home covered in mud after spending most of the day playing. His father, a shoemaker who often had to repair his son’s overused boots, wasn’t too happy at his son’s chosen profession, expressing doubts over the ability to earn money “kicking a leather ball”.

Those doubts, if they remained by the time Vado took to the pitch for the final, would certainly have dispelled by the end of it.

Vado were once more the hosts, welcoming an Udinese side who were not yet established and still a very modest club. Even so, they were bigger than Vado and in most people’s eyes the favourites.

For all of Udinese’s supposed superiority, however, this proved to be a true cup final where both sides struggled to carve an opening as the fear of losing overpowered any desire to win.

And then, just as a replay seemed inevitable, the improbable happened.

As one newspaper reported “here comes Levratto advancing towards the centre and anticipating the entrance of the black-and-white opponent, he faces the right back, feints on the left, advances and from 20 meters he lets go of a very strong shot…”

“Is it a goal?” the same Udinese fullback is said to have asked, hearing supporters cheer but seeing the ball bouncing behind the goal.

“The ball tore through the net,” the incredulous Udinese goalkeeper Libero Lodollo is said to have replied.

The youngster Levratto had just won the cup for his team. And, as he was triumphantly acclaimed by the watching crowd, he’d also given birth to the nickname that would follow him all throughout his career: sfondareti, or net-buster.

Indeed, for Levratto this would be the start of a magnificent career. Two years after winning the cup, he made his national team debut at the Paris Olympics, called up by Vittorio Pozzo despite still playing in the Second Division.

In the French capital he made the news for a remarkable episode in a game against Luxembourg. His exceptionally powerful shot connected squarely with the goalkeeper Bausch’s chin, causing him to collapse amidst the uproar of the crowd. Spectators saw blood coming out of the goalkeeper's mouth and some feared the worst. In the end was nothing as dramatic as that; the force of the impact had torn off a piece of his tongue, prompting medical attention on the sidelines. Remarkably, in an era where substitutions were yet to be introduced, the goalkeeper returned to the game.

In a subsequent play, the ball once again found its way to Levratto. As he prepared to take a shot, he noticed the goalkeeper covering his face with his hands out of fear of a repeat. Already leading 2-0, the striker opted to intentionally shoot the ball wide of the goalposts, displaying a sportsmanlike attitude that won him plaudits.

Four years later, Levratto was once again a star attraction of the Italian national team at the Olympics. He scored four goals in five games on the way to a bronze medal win. His myth was further cemented during a tie against Spain: Italian media from the era state his shot from the edge hit and sent two opponents into the goal, before breaking the net. In the match against Uruguay, his shot once again burst the opposition’s net.

Levratto stayed with Vado for a couple of years following the cup success. In 1925 he signed two contracts, one for Juventus and the other for Genoa. For the Football Federation the only valid one was the contract he’d already signed for Verona, the team for which he played and to which he had to remain whilst serving a ban before moving permanently to Genoa. Levratto wore the red and blue jersey for seven seasons, scoring 84 goals in 188 league appearances. In 1932 he moved to Ambrosiana-Inter and in 1934 to Lazio. He ended his career as a player-coach first at Savona, which he led to the victory of the Serie C championship 1939-1940.

He even tried his hand at management with limited success, even though he was an assistant to Fulvio Bernardini at Fiorentina when they won the scudetto in 1956.

Levratto was famous enough that in 1960 he was namechecked in the song ‘Che Centrattacco!’ (What A Forward Line!) by the jazz quartet Quartetto Cetra, a humorous ditty about a man who sees himself being a great goalscorer only to wake up and realise that it was a dream inspired by a poster of Levratto.

Levratto advancing on goal.

Photo Credit: Storie de CalcioFor all the great things that he went on to achieve, it would be wrong to imply that Levratto was the only reason for Vado’s success. The team was well led by captain Enrico Romano, nicknamed Testina d’Oro (Little Golden Head), because in one match he scored thirteen goals, all with his head. In a friendly match against the National Team, he impressed legendary national team coach Pozzo so much that he considered calling him up for the Italian national team, though this never transpired.

On the field with him were defenders Masio, Raimondi, Negro, and Antonio Cabiati, right winger Roletti, who had already played in Serie A with Savona, the strong centre forward Marchese, and Armando Esposto, often considered the team’s brain for his tactical acuity.

The heart of the team, however, were the three Babboni brothers – goalkeeper Achille, defender Lino and midfielder Giovanni Battista. The three had been among the founders of the club and had seen it develop from an idea discussed over drinks. Indeed, bars would play an important role in Achille’s life in particular: he would go on to marry the owner of a bar dedicated to his teammate Levratto and work there for the rest of his life.

Yet the presence of these players in itself is not enough to explain Vado’s victory. They had some skill and a lot of heart but they still would have lost had Udinese not underestimated the challenge in front of them. This attitude was not limited to their players as evidenced by an article from “Il Giornale di Udine” of July 11, 1922, in which the following was published: “to the fellow citizens there remains, now, only an easy encounter with Vado to conquer the well-deserved victory.”

When, to the contrary of expectations, the game proved to be far from easy, Udinese opted to defend in the hope that they could take the game back to Udine where they could close it off in front of a home crowd. It would prove to be a gross miscalculation on their part. History would not look kindly on them for with that defeat went their only opportunity of winning a major honour.

There are no photos capturing the Vado players celebrating with the trophy and not just because photography was still a rarity at the time. Instead, and for a reason that has been forgotten, this was only handed to the club a couple of months later in a sombre ceremony in the presence of local dignitaries.

Nor did they get to enjoy the trophy for long. After Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, the United Nations imposed economic sanctions on them. Even though these were mild and largely ineffective, the fascist regime took the opportunity to rally Italians to their nationalistic cause, organising a ‘gold for the nation’ manifestation where people were ‘asked’ to donate any precious metal to the state for it to fund their war efforts.

Vado were not excluded with the club being obliged to donate the Coppa Italia won over a decade earlier. Thus, a precious memento of Italian football was lost forever, melted for its silver.

That was as good as it got for Vado who never made it to the topflight; the 1920s were their golden years as they took in four Second Division campaigns between 1922 and 1926. More recently they won the Eccellenza Liguria championship in 2018-2019 and made it into the Serie D. That’s where they have remained since although on two occasions they were technically relegated before being reinstated due to other sides withdrawing from the league.

In 2023 they won the play-off for their regional grouping in the Serie D although this did not win them promotion; in the convoluted structure of Italian football those who win the play-offs at this level only win the opportunity to be considered should a side in the Serie C fold. None did on this occasion. Still, it was a memorable encounter against Sanremese with Vado’s winner, in typical fashion, coming deep into extra-time.

For all their failure to progress, passion for football has continued to shape the lives of people from Vado. Valerio Bacigalupo, the goalkeeper of the Torino side that perished at Superga, began his career as a teenager with Vado as did his brother Manlilo who left Torino before the tragedy and went on to enjoy a long career first as a player and then as a manager.

Then there was Pedro Luis Rossi, an adventurer who travelled to Argentina where he became an administrator at River Plate in the 40s and 50s having first kicked a ball in the tiny town of Vado. A similar journey was undertaken by Vessilio Bartoli who won two national titles as manager of Sportivo Luqueno in Paraguay, coached the Paraguay national team, and won a title in Ecuador with El Nacional before returning home to manage Vado.

Poster celebrating Vado’s cup win.

Photo Credit: Storie de CalcioLike the winners of the Coppa Italia, these men remain important figures only in this particular corner of Italy. Vado never really got the opportunity to defend their title, much less build on their reputation. The schism in Italian football came to an end soon after their cup win and, with a full league in progress the following season, there was no space for a cup competition.

This served as a double punishment for Vado. The agreement put together by Emilio Colombo, ensuring that the big clubs returned within the FIGC’s fold, had been signed a month before the cup final. It was good news for Italian football but not as much for Vado who, having won their league were deprived of promotion to the topflight, squeezed out by the returning giants.

The FIGC made an attempt to kick-start the Coppa Italia in 1926 but it proved to be impossible to find dates when games could be played and the tournament was abandoned. It was only in the mid-1930s when a restructuring of Italian football took place that made it possible for a cup event to be held and the Coppa Italia finally found its feet. From 1935 onwards it became a staple of Italian football, continuing play even as World War 2 raged on in Europe.

Vado played in a smattering of editions of the pre-war Coppa Italia, winning the occasional game but never two in a row. There would be no further giant-killing for them.

That’s also because the nature of the Coppa Italia changed dramatically once it really got going. The egalitarian ideals present at its birth were dropped and it became a closed competition in which only to the clubs of the top three divisions could compete. Once Vado no longer formed part of that group there was no way back in for them.

It is a circle that has closed even further as the years passed, so much that for the past few years only clubs from the Series A and B have been allowed to compete. The demands of the big clubs – their desire to exclude others that was at the basis of their breakaway in the 1920s – has been fulfilled.

Vado FC in the modern day.

Photo Credit: Eric ParodiHaving been forced to donate the cup, all that was left for Vado were the memories and echoes of that memorable triumph.

At least in 1992 they were bestowed with a replica of the cup by the FIGC. Then in December of 2022 Vado once again took on Udinese in a game to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the final. This time Vado won 3-0 even if Udinese – a Serie A side – had a valid excuse for this defeat: on this occasion they’d played a mix from their Under 17s and Under 18s.

Vado appreciated the gesture and enjoyed the rematch. Yet the fact that Udinese couldn’t manage to put together an eleven made up of senior players to mark such a momentous game signalled just how big the gap between the two clubs had grown over the course of a century. The two clubs could play in different continents, such is the likelihood of either getting to face each other in a competitive game ever again.

That is Vado’s reality; a club that had one shot at glory and grabbed it. It is a piece of their history that will echo for as long as the game is played. In 2022 a group of local artists were engaged to draw a mural featuring the Coppa Italia-winning eleven outside the stadium. This heralds to fans – local and visiting alike – of that wondrous achievement; of a moment in time when a minnow could pull off a cup giant-killing, even in Italy.

A reminder of when Vado FC was the talk of Italian football.