Words by Leire Martinez | Published 12.12.2025Athletic Club de Bilbao is a team closely linked to the socio-economic and political context surrounding it. It was founded in 1898, the very year in which Spain lost its last colonies in Asia and America in what became known as the ‘disaster of '98’, an event that led to regionalist and nationalist movements regaining strength throughout Spain at that time. In the specific case of the Basque Country, the nationalist movement was organised around Sabino Arana, who founded the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV, by its acronym in Spanish) just three years before the birth of Athletic Club, and the ties between the two have been close since the beginning. A clear example of this is the first Lehendakari (or President) of the Basque Country, José Antonio Aguirre, of the PNV, who was a player for Athletic Club during the 1920s and played 46 matches for the club.

The Athletic Club side of 1923 who won the Copa del Rey.

Photo Credit: WikiMedia CommonsThis historical relationship between the club and the political party is an essential characteristic that has remained unchanged over time, and which author Mariann Vaczi, in her book Soccer, culture and society in Spain: an ethnography of Basque fandom, captures in a quote from politician Andoni Ortuzar: ‘To be “a real Bilbaíno”, you have to be a fan of three things: the Virgin of Begoña, the PNV, and Athletic Club’. Andoni Ortuzar belongs to the PNV, the party that has governed the Basque Country almost uninterruptedly since the arrival of democracy to Spain, almost always in coalition with other parties, but generally with a majority. The quote reflects that the Basque Nationalist Party is an entity with a strong presence in all institutions and levels of government in the province of Bizkaia, and especially in its capital, Bilbao. Many Bilbao residents, in fact, recognise that the values of Athletic Club and the party are similar.

And what are those values? Well, mainly Basque nationalism; the preponderance of ‘Basque’ above all else. In the context of Athletic Club, this is clearly seen in its transfer policy, which is determined by a philosophy that, in 1912, with the departure of the last foreign player who played for the team, established that no player who was not from Biscay could play for the club. Over the following decades, and especially since the 1970s, this policy has become somewhat more flexible, and today, according to the club's website, the sporting philosophy "is governed by the principle that players who have come through the club's own youth system and those trained in clubs in Euskal Herria, which encompasses the following territorial divisions, can play in its ranks: Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, Araba, Nafarroa, Lapurdi, Zuberoa and Nafarroa Behera, as well as, of course, players born in any of these areas".

This parallelism between the spirit of Athletic Club de Bilbao and that of the Basque Nationalist Party, this identification between the two, means that the club is strongly supported by public and public-private institutions in the Basque Country. This is demonstrated by the fact that the new San Mamés stadium was financed by the club itself, the Basque Government, the Provincial Council of Bizkaia, Bilbao City Council and Kutxabank, one of the main Basque banks. This support - financial, institutional and political - also makes Athletic Club de Bilbao by far the richest club in the Basque Country and therefore the one with the greatest capacity to attract players.

The interior of San Mamés, home of Athletic Club.

Photo Credit: WikiMedia CommonsFor many decades, this philosophy was enough to produce world-class players who played for Athletic Club and helped it win titles. José María Belauste, Rafael Moreno ‘Pichichi’, Guillermo Gorostiza, Piru Gaínza, Telmo Zarra, José Ángel Iribar, Julen Guerrero and Aritz Aduriz, among others, contributed to the club winning several leagues, Copa del Rey trophies, Spanish Super Cups and other lesser-known trophies. However, since the beginning of the 21st century, and especially during the last 15 years, football has become hugely globalised and, as a result, the demands and competitiveness have also increased. This makes it difficult for teams with philosophies such as Athletic Club's to build squads that can stand up to the biggest teams.

In order to address the situation, and bearing in mind that signing players who do not follow the philosophy is not even considered, the club has strengthened its presence throughout the Basque Country by signing agreements with various feeder clubs, something it has been doing for several years. Currently, Athletic Club, in addition to having its own very strong youth academy in Lezama, has agreements with 179 grassroots football clubs, both male and female, spread across the seven Basque provinces mentioned above. Thanks to this, it has access to more than 21,000 players and more than 1,900 coaches. This represents an enormous influence in a geographically small territory of around 20,900 km2, with a total population of around 3,000,000, which is slightly less than the population of just the city of Madrid.

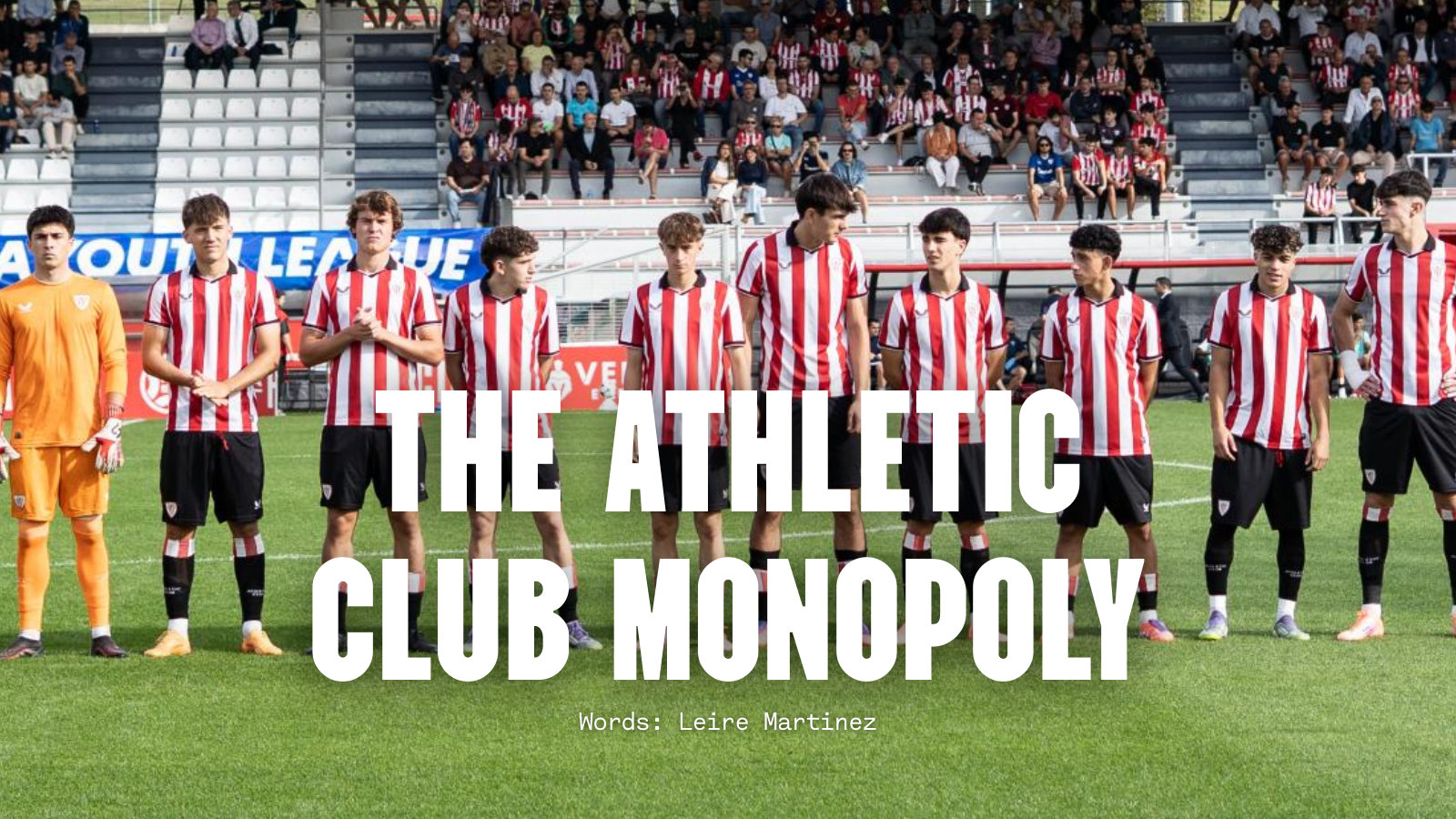

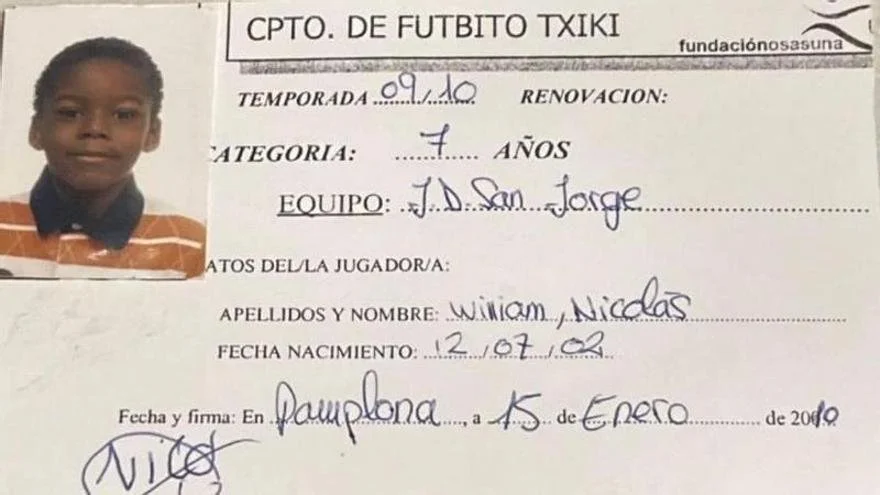

This strategy, combined with the political and financial support it receives from institutions, has made it the first choice for many players, even ahead of teams that, due to their geographical location, history or influence, they should sign for. This is the case, for example, of Unai Simón, the current starting goalkeeper for the team and the Spanish national team, who was born in Murgia, Araba and, instead of ending up in the Deportivo Alavés youth academy, joined Lezama at the age of 14, or Mikel Vesga, who moved from the Alavés youth academy to Lezama at the age of 21 and has already represented Bilbao's first team in more than 250 official matches. Perhaps the most striking cases, and the ones that have caused the most controversy in recent years, are the Williams brothers, Iñaki and Nico, who were formed by and trained with teams in the city of Pamplona before joining Athletic Club.

Nico Williams’ player profile while he was playing with CD San Jorge.

Photo Credit: Noticias de NavarraThis supremacy of Athletic Club de Bilbao over the rest, in a region full of historic football teams (Real Sociedad, from San Sebastián; Real Unión, from Irún; Deportivo Alavés, from Vitoria; Sociedad Deportiva Eibar, from Eibar; Club Atlético Osasuna, from Pamplona; to name a few of the best known and corresponding to the most populated cities in the Basque Country) generates a lot of unease among the other clubs, and especially among the population of the provinces other than Bizkaia, as it is seen as ‘unfair competition’.

None of the aforementioned clubs have as much institutional and financial support as Athletic Club, and therefore find it impossible to compete: they cannot offer contracts like those offered by Athletic Club, they cannot build scouting networks like those of Athletic Club, and they cannot establish agreements with partner clubs like Athletic Club does. The latter became clear again this past summer, when Croisés Bayonne, which until then had an agreement with Real Sociedad, became part of Athletic Club's youth football structure for the next ten years.

Athletic Club after signing a 10-year agreement with Croisés Bayonne.

Photo Credit: Athletic ClubAnother point that causes discomfort among any football fan in the Basque Country who is not a supporter of Athletic Club is the fact that the club's transfer policy is spoken of as something special, something unique. However, when a player from a rival team ends up joining Athletic Club, what traditional fans of Real Sociedad, Deportivo Alavés or Club Atlético Osasuna perceive is that something ‘that is theirs’, ‘that belongs to them’, is being taken away from them; a player who, due to his outstanding level, can help their team not only to survive but also to thrive and, if we dare to dream, to win a title during certain years of his career. A very representative example here is the case of the Williams brothers, who have become world-class players after growing up playing football in Pamplona.

Athletic Club Bilbao is, now more than ever, an entity that absorbs the best of all the youth academies and feeder football teams around it. As soon as a player shows the slightest promise anywhere in the Basque Country, Athletic Club is always the first to snap him up. This creates huge inequalities between teams: on the one hand, competitive inequalities, because Athletic Club gets a good player and, at the same time, prevents that player from developing his career in his home team; on the other hand, economic inequalities, not only because in many cases the bulk of the expenditure on the player's training is borne by the home club, but also because it is Athletic Club that reaps the benefits of a possible future million-euro sale.

It cannot be denied that, sadly, football in the 21st century requires ever-increasing financial investment. However, not everyone has equal access to this investment, which creates many economic and competitive inequalities. This is why the support of councils, local and provincial governments, and public-private institutions is so important. But this support should be as equitable as possible; ultimately, the clear reflection of a healthy, interesting and evenly matched competition should be the existence of several teams at the same level, able to compete against each other to win trophies. However, this is not what is happening in the Basque Country at present, where Athletic Club de Bilbao stands out from the rest, even against Real Sociedad, both in terms of its economic capacity and its youth academy structure and agreements with feeder clubs, which has led to the establishment of a de facto monopoly, thanks to which Athletic Club always has the upper hand. This loss of competitiveness and diversity, anywhere but especially in a region where football is deeply rooted, is a real shame.

The situation is very difficult to resolve, given the current state of affairs. The only thing left for us to do seems to be to hope that, in the not-too-distant future, the government will somehow change its mind and begin to take other teams into account. Only then will it be possible to challenge the monopoly of Athletic Club de Bilbao on Basque Country’s feeder clubs.